Maintaining a Private Cult

An essay and a recipe for borscht. Words and photographs by Sam Dolbear.

Good morning and welcome to Cooking From Life: a Vittles mini-season on cooking and eating at home everyday.

All contributors to Vittles are paid. This is all made possible through user donations, either through Patreon or Substack. If you would prefer to make a one-off payment directly, or if you don’t have funds right now but still wish to subscribe, please reply to this email and we will sort this out.

All paid-subscribers have access to the back catalogue of paywalled articles. A subscription costs £5/month or £45 for a whole year.

If you wish to receive the newsletter for free, or wish to access all paid articles, please click below. You can also follow Vittles on Twitter and Instagram. Thank you so much for your support!

Cooking from Life is a Vittles mini-season of essays that defy idealised versions of cooking – a window into how food and kitchen-life works for different people in different parts of the world. Cooking as refusals, heritage, messiness, routine.

Our fifth writer for Cooking from Life is Sam Dolbear.

Maintaining a Private Cult

An essay and a recipe for borscht, by Sam Dolbear.

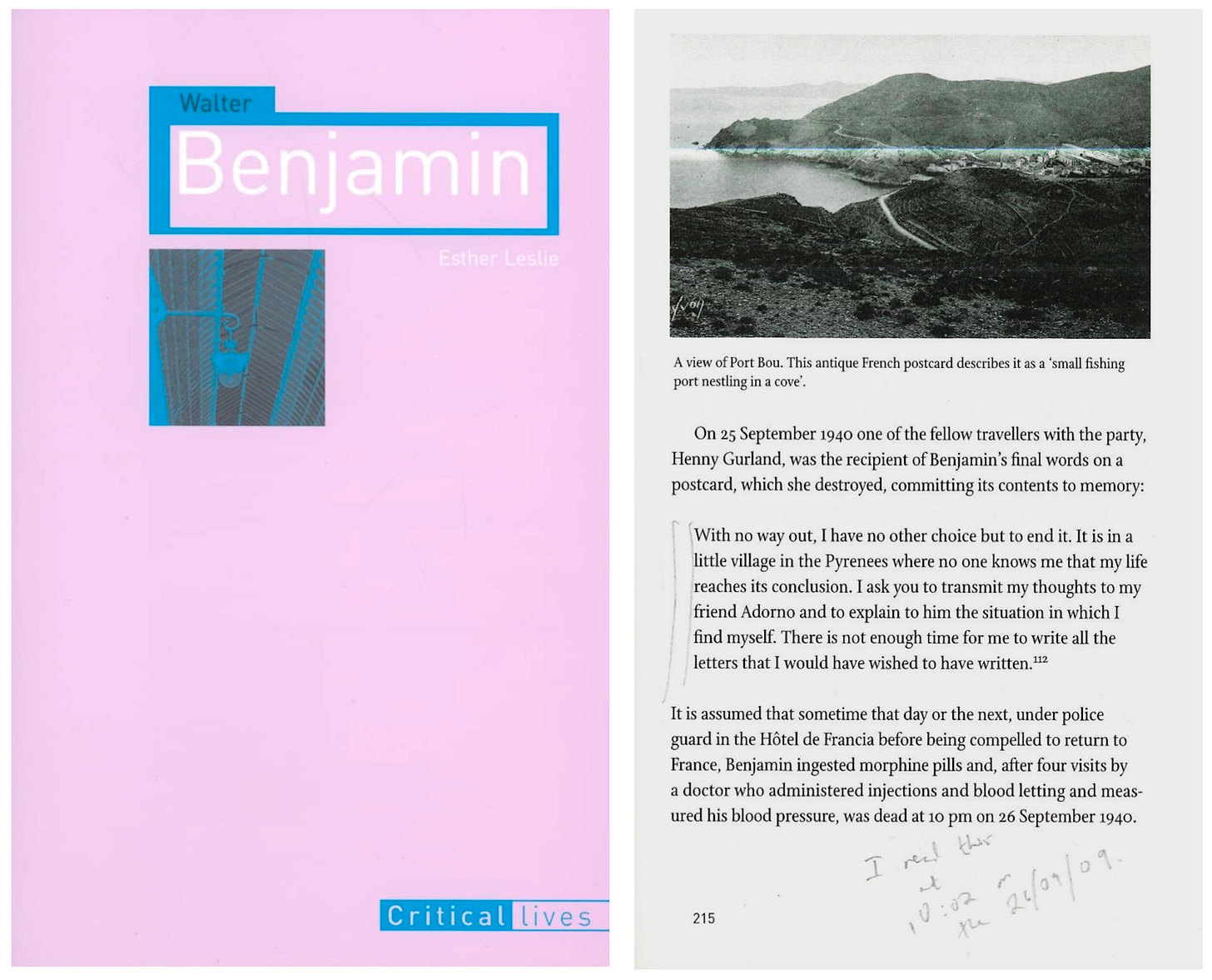

Fifteen years ago I finished reading Esther Leslie’s short biography of Walter Benjamin. I have a strong memory of the scene: I was in a small single bedroom at my parents’ house (where I’d never lived), and there was strangely a cheaply-made rocking chair in the living room left over from the previous tenants. Leslie’s biography culminates with Benjamin’s attempted escape from Nazi-occupied France; his trek over the Pyrenees, named as the ‘midnight of the century’. The last page quotes Benjamin’s final letter, to his friend Henny Gurland ‘With no way out, I have no other choice but to end it’. And so there, on 26 September 1940, in the Hôtel de Francia, not far from the water, he ingested morphine pills and, after four visits by a doctor, was declared dead at around 10pm. This is a story told often, at one point Benjamin was even to be portrayed by Colin Firth, only for him to appear on Netflix more recently, played by Moritz Bleibtreu.

Back then, I had a habit of writing a date and time and location in the backs of books when I finished them – given, perhaps, that it was a rare event and feeling when I did. As I came to check the time and date when I finished the Benjamin biography, I realised it was just after 10pm on 26 September 2009: exactly sixty-nine years after Benjamin’s death. I remember feeling overwhelmed – not just with the story of Benjamin’s life and death, but also with how I first encountered it, as an almost other-worldly moment of serendipity. I wrote the time and date out in my copy. Did I just commune with a spirit?

From this day 26 September became marked in my calendar as a feast day, a day of uncertain mourning. In 2015 I met up with some friends to mark the seventy-fifth anniversary of Benjamin’s death. Everyone brought the things to eat and drink that he had written about in a series of short articles called ‘Food’ for the Frankfurter Zeitung in May 1930. We ate and drank in the order of the fragments. We had fresh figs, then café crème, Falernian wine and stockfish (which, with our limited resources, became supermarket wine and mackerel), borscht, pranzo caprese, with a mulberry omelette at the end (which became blueberry or blackberry omelette). We read the passages aloud to each other as much as to the food. They spoke of borscht prepared with snowflakes fallen from the sky, figs bought in paper bags on an Italian hillside that were so ripe that they ruined a letter in his pocket, and children who transformed marble tabletops into frozen seascapes.

I prepared the borscht on that day in 2015, and I’ve made borscht every 26 September since. In 2016 and 2017 I cooked it in two different apartments in Lisbon, where I lived at the time. In 2018 and 2019 I made it in two different flats in London. In 2020 I had just moved to Berlin and ate borscht and drank vodka with a friend. That day we also read Christa Wolf’s One Day a Year out loud to each other – a book which chronicles each 27 September (the day after Benjamin’s death) since 1960. Wolf never ate borscht on this day, but she does describe eating buckwheat groats and soft-boiled eggs for breakfasts and various pasta and salad dishes for dinner.

In 2021, I again cooked solo, in a different flat in Berlin, this time using a recipe from a Polish friend I Zoomed with, who even told me to listen to certain pieces of music at certain parts of the process. And last year I didn’t have enough time to cook, so I instead ate it at a Russian restaurant near my work, this time with piroshkis (as Benjamin also describes eating in his fragment on borscht). As I walked over to the restaurant I sent a voice note to all the people I’d have liked to eat borscht with, reading out Benjamin’s fragment on borscht as I walked. I then sat alone and felt the soup hit my body like a drug or a mask of steam, as he describes it in the fragment.

Every year I sought to perfect the recipe, never getting close, sometimes getting further away. I tried new recipes, asked for tips and takes online, and spoke to various people. I made the borscht with different amounts of heat, time, but also varied the crucial elements: dill, sour cream, lemon and vinegar. I started out making it vegetarian, but later thought it needed fragments of meat and bone to add a depth of flavour, a beefiness. It never quite worked, though, because it did not transport me back to the time when I ate it with friend in Odesa train station in 2011, my formative borscht experience. But the point was perhaps different: it was to clear a day, to stew over a pot as it stewed, to think about the experience of a single life and how that life can stand in for so much more. Whenever I cook borscht, I think ambiently about Benjamin, a person I never met, as much as I try to displace him and his particular life and death, and to think instead about the various people I have known and lost: my aunt in 1997, my grandmother in 2006, two friends in 2019, a music teacher in 2020, a cousin in 2022.

After I started to share my borscht ritual with others, a friend told me she’d make a bowl for me. She did, and it’s one of the most precious objects I’ve ever owned. It has a B on it: perhaps for ‘Benjamin’, perhaps for ‘borscht’, or perhaps for ‘bowl’. On Seudat Havra’ah – the Jewish meal of recovery or consolation – circular foods such as eggs, lentils, beans and bagels are consumed after funerals, for they represent the circularities of life and death. I wonder if I have invented a ritual of my own circles, via Benjamin, via bowls, to circle back to one day a year, to think about how this one person might stand in for a multitude of nameless others, a sentiment inscribed on a monument to Benjamin in Port Bau where he died. If I ever make it well, I wonder if I might have to stop.

Walter Benjamin Borscht

For this year’s borscht I will make a variation of 2021’s recipe, from the wonderful Joanna Klass, who also recommends listening to Prince’s ‘Purple Rain’ and Mozart’s ‘Requiem’ while cooking.

Serves 8–10

Ingredients

1kg raw beetroot

2 tablespoons olive or vegetable oil

2–3 carrots, diced

1 celeriac, diced

1 onion, diced

3–4 litres beef or vegetable stock

2–3 medium yellow potatoes, peeled and diced

¼ savoy cabbage head, cut into thin ribbons

2 handfuls of parsley, roughly chopped

Juice of 1–2 lemons, or to taste

½ tablespoon sugar, or to taste

Salt and freshly ground black pepper, to taste

300ml soured cream

Small bunch of fresh dill, finely chopped

Method

Start by preparing the beetroots. Wash them, cut the stems off and boil for 30– 40 minutes with their skins on. (You can also roast them whole in tin foil so they keep their colour.) While the beets cook, prepare the rest of the soup.

Heat the oil in a large pan over a medium low heat and add the diced carrots, celeriac and onion. Cover with a lid and cook for 10 minutes or so, stirring often, so the vegetables sweat but do not brown.

Pour the stock into the pan and bring to a simmer, then add the potatoes, cabbage, and parsley. Leave to bubble gently while you tend to the beetroots.

Remove the boiled beetroots from the pan and put them into very cold water to preserve the colour. After they cool, remove the skin with a not-too-sharp knife. Coarsely grate them. (If you’re worried about staining your fingers, you can wear gloves.)

GRAND FINALE! After 25–30 minutes, once the soup vegetables are tender, add the grated beets. The soup should instantly become a deep red. Now taste it. Add the lemon juice, sugar, salt and pepper to taste, then stir in half of the dill. The borscht should be spicy, sweet and sour and you should want to eat it!

For the table: the remaining dill in a little dish, a bowl of soured cream, some more lemon, salt and pepper. Guests should garnish and season the borscht to their tastes.

Note: If you’d prefer to make your stock from scratch, boil 500g of beef with bones in 4 litres of water, with an onion simply sliced in half added to the pan. Add the allspice or pimento, a bay leaf, 5–6 black whole peppercorns and a tablespoon of salt. At the end of the process add a cube of beef stock to taste. For a vegetable stock: boil down porcini mushroom, celery, carrots, a bay leaf, black pepper and salt and do the same at the end with bouillon.

Credits

Sam Dolbear is a writer, researcher and teacher based in Berlin. He is currently completing two books, one on the palm reader Charlotte Wolff (with Ma Bibliothèque) and one on the radio-producer Ernst Schoen (with Goldsmiths Press). He has a newsletter at Cosmic Reductions https://raeblodmas.substack.com .

Vittles is edited by Rebecca May Johnson, Sharanya Deepak and Jonathan Nunn, and proofed and subedited by Sophie Whitehead.

Thank you - from a fellow Benjamin devotee - for this interesting and moving article

Wonderful. Add all us readers to the circle