Mechanical Reproduction in the Age of Gregg Wallace

The British obsession with food factories. Words by Sean Wyer; Illustration by Sinjin Li

Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 5: Food Producers and Production.

All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £500 for writers and £200 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations, either through Patreon or Substack. If you would prefer to make a one-off payment directly, or if you don’t have funds right now but still wish to subscribe, please reply to this email and I will sort this out.

All paid-subscribers have access to the back catalogue of paywalled articles and all upcoming new columns, including the last newsletter on the North Circular Road. It costs £4/month or £40/year ─ if you’ve been enjoying the writing on Vittles then please consider subscribing to keep it running.

If you wish to receive the newsletter for free weekly please click below. You can also follow Vittles on Twitter and Instagram. Thank you so much for your support!

On a particularly lazy Boxing Day afternoon last year, my channel hopping alighted on the 1968 children’s film Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, a mainstay of my VHS collection that I had not watched for at least a decade. I was struck by the strange darkness at the heart of the film ─ not just the child catcher, but the reasons behind the child catcher (a baroness who is physically unable to have children so she rounds up every child in the land so she is never reminded of them). For a film you thought was about a flying car, there are various unexpected personal subplots: the depression of a man whose wife has left him as the sole parent of two kids, the sadomasochistic relationship between the Baron and his wife. But if you strip the film down to its plot elements, and discard the bits which are stories within stories, then you can say Chitty Chitty Bang Bang is actually about an artisan sweet manufacturer who decides to sell his recipe to a famous sweet producer, upgrading his rickety set up for the might of the British industrial factory.

Now within the context of children’s films from this time, this real plot beneath a plot isn’t exactly unusual (Mary Poppins, after all, is not a film about a nanny but an anti-capitalist critique of the British banking system and its codependency with the exploitation of colonial resources). But I think it’s significant that Chitty Chitty Bang Bang is a British depiction of factory production. In the song Toot Sweets, the factory floor is portrayed as an clean, open space where quality is produced and monitored (the tastings suggest that there is no homogeneity in the factory method). It’s a wonderland of colour: yellow lollipops, dark green boiled sweets, pink and white sticks of rock, orange toffees, gleaming brass stills. In Chitty Chitty Bang Bang’s vision of Fordist labour, the workers do twirls and cartwheels.

After reading Sean Wyer’s newsletter today, you may agree with him and me that this could have only been a British film. Chitty Chitty Bang Bang is only one of many sympathetic depictions of the British food factory (both real and fictional) that have existed ever since the factory became largely responsible for the way we eat. From early 20th century propaganda films right up until an early 21st century TV series presented by a perpetually horny bald grocer, we do not lament it as an encroachment on traditional foodways, but celebrate it as a technological achievement. This is perhaps understandable ─ it is, after all, as I mentioned in the last newsletter, our true legacy on food culture and production. Yet as Sean points out, our fascination with the factory rarely extends to the very thing that keeps it running: the producers themselves.

Mechanical Reproduction in the Age of Gregg Wallace, by Sean Wyer

In his English boarding school, a young Roald Dahl dreamt of chocolate factories. His imagination was fuelled by news stories about what went on behind closed doors at confectionery rivals Cadbury and Rowntree, who were known to send spies into one another’s factories to steal trade secrets. When, in 1964, Dahl released Charlie and the Chocolate Factory – a novel which describes children and adults similarly desperate to see inside such a place – it was still possible for the public to realise his dreams: Cadbury hosted regular guided tours of its Bournville manufacturing site until 1970, when it finally closed its factory doors to the public. Two decades later, the tours were replaced by Cadbury World: an entertaining simulacrum of the chocolate-making process, but a theme park-like ‘experience’ rather than a factory tour.

When a TV news reporter asked why Cadbury’s popular tours were ending, the head of the company’s visiting department explained that ‘increasing automation’ had ‘robbed the visitor of some of the more interesting facets of the work.’ The assumption was that visitors went there to watch Cadbury’s chocolatiers practising their craft, and were far less interested in the monotony of mechanised production.

Karl Marx would probably have been surprised that Cadbury’s tours had ever been in demand. In Volume I of Das Kapital, written just over a century before Cadbury’s final factory tour, he suggested that consumers were not particularly bothered about how their food was made: ‘In the act of eating,’ he wrote, ‘it is of no importance whatsoever that bread is the product of the previous labour of the farmer, the miller, and the baker.’

Marx may have foreseen many things with prescient accuracy, but the rise of Gregg Wallace was not one of them. Since 2015, Wallace has been a host on the BBC show Inside the Factory, where he shows viewers how some of the UK’s favourite industrially produced foods – from biscuits to baked beans – are made, by following the products from raw material to finished commodity. Wallace is anything but indifferent to the repetitive whirring of the machines that produce much of our food – on the contrary, he seems mesmerised by the sheer scale, speed and efficiency of modern industry.

Wallace’s excitement is infectious. We may not quite believe him when he says he had never previously given a second thought to how supermarket staples are made – he is a former greengrocer and a MasterChef presenter, after all – but millions of us nonetheless follow him on his voyages of discovery. He is not the only person curious to find out how instant coffee is made, or how molten chocolate can be poured onto a Magnum without melting the ice cream.

The urge to glimpse ‘Inside the Factory’ comes partly from the draw of the unknown. There is something tantalising about peering into what Marx calls the ‘hidden abode of production.’ Marx and Wallace both understand this well: as Marx offers to sneak us across the threshold of the factory and reveal its mysteries, so too does Wallace promise to share his ‘privileged access’ with us. In both cases, we are encouraged to feel the adrenaline that comes from trespassing. Our guides are letting us in on a secret.

Except, of course, that programmes like Inside the Factory are not sharing secrets at all – instead, they showcase recipes or techniques that are never actually divulged to the viewer. Like Arthur Slugworth, Willy Wonka’s rival in Dahl’s novel, Wallace tries to charm factory employees into revealing the ‘trick’ – but, with a smile, they invariably keep their cards close to their chests. (Of course they do; their employers are watching.) By refusing to reveal how the trick is performed, the impression Inside the Factory gives is that these manufacturers still have something magical up their sleeves.

The food factory has long loomed large in Britain’s cultural imagination, with the Industrial Revolution and the economics of imperialism making it an early and enthusiastic adopter of industrial food processing. The historic circumstances that propelled Marx to examine the ‘unlimited extension of the working day’ in London’s round-the-clock bakeries are the same ones that inspired Dahl’s sweet-toothed dreams, and that also fuel Britain’s intimate relationship with processed foods today.

Brands like Cadbury, alongside others featured on Inside the Factory, such as McVitie’s and Mr Kipling, are often perceived as quintessentially British. No matter where their parent companies are headquartered, or where in the Global South their ingredients are farmed, British national identity is interwoven with the homogenised, highly processed foods they produce. British factories may elicit mystery or intrigue, but they are less often viewed with suspicion or fear – as they are in many other countries.

Early in the twentieth century, the US saw polemics like Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, an early indictment of the American meat-processing industry. In French and Italian representations of industrial food production, it is common to lament the threat that factories pose to culinary traditions. In China, the popularity of rural, back-to-basics ‘cottagecore’ videos, often centred around food culture, can be read as a critique of rapid urbanisation. A Bite of China, a popular food documentary produced by the Chinese state broadcaster CCTV, hardly features factories at all, instead training a rose-tinted lens on the lives of growers and producers.

In British food documentaries, on the other hand, the factory itself often takes centre stage, and is even presented with the same reverence A Bite of China reserves for its artisans; Channel 4’s Snackmasters, which challenges chefs to recreate industrially produced food in a commercial kitchen, best epitomises this. Fuelled by the British obsession with the ‘magic’ of the food factory, which Roald Dahl harnessed so masterfully, the usual conclusion – that you or I could never come close to recreating KitKats or Quavers at home – is pushed even further. Not even highly trained artisans can quite get it right.

Inside the Factory, meanwhile, celebrates artificial intelligence, around-the-clock manufacturing, and the sophistication of twenty-first-century industrial methods. On occasion, the show glances back in time, with historian Ruth Goodman exploring how food was made before mechanisation. The effect is to contrast the back-breaking labour of yesteryear with the efficiency of today. According to this logic, history is a straight line, from a bleak past towards an ever-brighter future.

In one episode of Inside the Factory, Wallace interviews a long-serving employee of a dairy factory who explains that, before the distribution process was automated, he ‘effectively was a robot.’ On the surface, there seem to be no losers from technological progress. The remaining employees get less boring work; their boss saves a fortune: ‘A robot never phones in sick,’ Wallace jokes. We are told that 300 people would have worked in the distribution hall before automation. What happened to them afterwards is never addressed; Wallace never asks the question.

In the early 2000s, many of my school friends’ parents worked at Sun Valley, a chicken processing factory in Hereford founded by Lieutenant Colonel Uvedale Corbett, who was known locally as ‘The Colonel’ long before KFC arrived on the West Midlands chicken scene. The rest of us listened intently to the fanciful stories our friends told about their parents’ workplace, including one in which the factory employed a priest to bless each chicken heading for slaughter. As well as demonstrating a shaky grasp of theology, our credulity showed just how clueless we were about the meat-processing industry.

The Chicken Factory, a 1988 BBC programme about Sun Valley, begins by following the familiar formula we recognise from Inside the Factory. We see the products – chirping yellow chicks – zooming along on a belt, being sorted into boxes. The employee explaining the process feeds us large numbers without any real context; an attempt to demonstrate the efficiency of the factory and its workers.

Minutes in, however, we realise that we are not watching a ‘normal’ programme about food production. The scene fades to my old secondary school, Aylestone, where final-year pupils are half-heartedly singing their last hymn in the assembly hall. The presenter interviews a pair who are due to start work at the chicken factory the following week. We get the most valuable and intimate insights into the lives of Sun Valley workers from the scenes filmed outside the factory.

The presenter asks the pupils directly: ‘Did you think that’s what you were going to be doing when you were studying at school?’ ‘No, no no no,’ replies the boy. ‘So you had more ambitions than that?’ the presenter asks. So far, so patronising. But the fictional premise that is so central to Inside the Factory – that everybody working in food production is delighted with their job – has already been broken here.

The Chicken Factory is not a revolutionary documentary, but it is quietly subversive. In Inside the Factory, while we do hear from a spectrum of workers, managers and owners, they seldom, if ever, contradict one another. In The Chicken Factory, on the other hand, we still hear from managers, but their assessments of the factory conflict with the voices of those working on the production floor.

‘Not everyone wants to go on to have the pressures in life to earn high wages,’ a Sun Valley manager says. ‘Some are quite happy just to earn a living.’ An interview with a young couple, engaged to be married, casts doubt on the idea that working at the factory allows them to do this, though. ‘For a man it’s not very good wages,’ the woman explains, with her fiancé in view. ‘But for me it’s OK, so long as both of us work [ . . . ] We still have to do so much overtime, really, to keep us going.’ Her fiancé tells us he works at the factory seven days a week.

Towards the beginning of the documentary, we see the new employees learning the ropes. They are being introduced to the dangerous ‘shackles’; these are used to hang dead chickens, but can also trap workers’ fingers and drag them along the production line. ‘It’s a good company, they do look after you,’ the instructor insists, but it is clear that corporate paternalism has its limits.

We are shown scenes of chickens being butchered at speed, and of carcasses thrown unceremoniously onto large piles of meat. But some of the stories we are told by the factory workers are also unsettling. Interviewed in his garden, one of the workers tells us how he dreams of ‘waking up one morning in a chicken shed,’ before ‘great big chickens’ come in to deliver him to the factory.

He is smiling at first, as if to suggest, ‘What a silly imagination I have!’ Over video footage of chicks in cages, he continues: ‘Fancy just waking up one morning and finding some great big chicken walking towards you, with hands, or something stupid like that, and grabbing you, throwing you on a lorry. And then you’re just whisked away about twenty miles, and you don’t know what’s going on. Next thing, you arrive at the factory and boom.’

It feels depressing that, in comparison to today’s Inside the Factory, 1988’s The Chicken Factory looks positively radical, although it is nothing of the sort. It is messy and ambiguous, however – neither a whistleblowing exposé, nor a glistening infomercial – and therefore human. This contrasts with Inside the Factory, which always depicts food processing as seamless.

The one major exception to this is a special series of the show called Keeping Britain Going, produced in 2020 during the first Covid-19 lockdown. It revisits factories that had previously been featured on the programme to see how they are adapting to the pandemic. According to the episode of Keeping Britain Going set in the McVitie’s factory in Park Royal, London, up to 20% of the McVitie’s workforce was off sick during the first lockdown. An uptake in demand led factory managers to ramp up production and to lengthen the hours of remaining staff. This is described on the show as ‘putting in the extra mile,’ which implies that taking extra shifts is akin to a patriotic duty. A haulage driver who slept in his cab overnight and then worked the next day is congratulated for his ‘can-do attitude.’ The programme never asks whether ‘sacrifices’ like this are strictly necessary for the Covid-19 ‘war effort.’

There’s a feeling of wartime propaganda about Keeping Britain Going. Indeed, the UK’s first notable propaganda film, Britain Prepared (1915), features scenes from a military bakery, operating with a factory-like efficiency. In the chapter of London’s Kitchen about the McVitie’s factory, Catherine Flood notes that the brand imagines itself as a great unifier in times of crisis. ‘The country may be imploding, but we all still share the love of biscuits.’

The onset of lockdown saw an increase in demand for groceries, but particularly for foods like biscuits, which provide easy fuel throughout the day. They are seen as essential in the home worker’s arsenal. As with earlier food factory documentaries, Keeping Britain Going never entertains the possibility that some of its audience members might work in the industry themselves. Instead, ‘we’ (the viewer) are assumed to be working from home, and to be thankful for ‘their’ (the worker’s) work making ‘our’ biscuits; just as the viewers of Britain Prepared are supposed to be grateful for the sacrifices of soldiers in the First World War.

Watching Keeping Britain Going, you would be forgiven for thinking that the companies featured are charities, selflessly volunteering to feed the nation. But they are not. It was the profit motive, not pure altruism, that made factories ramp up production during the early months of the pandemic. In many cases, shareholders were rewarded accordingly; the parent company of McVitie’s, United Biscuits, experienced a ‘pandemic boost’ in 2020, with pre-tax profits up 18.3% on the previous year. That did not stop McVitie’s from announcing the imminent closure of its Glasgow factory in May 2021, causing 400 workers, many of whom will have worked overtime to ‘Keep Britain Going’, to lose their jobs.

There is no one reason why Britain’s mainstream food factory documentaries are so rarely nuanced. Perhaps the answer has something to do with the sophistication of the twenty-first-century PR machine. Perhaps television commissioners believe that working in a labour-intensive food factory is too jarring, too incompatible with the Thatcherite illusion of a post-industrial Britain to bear thinking about. Perhaps they are more pressured than ever to choose viewing figures over political relevance, and assume that they cannot achieve both.

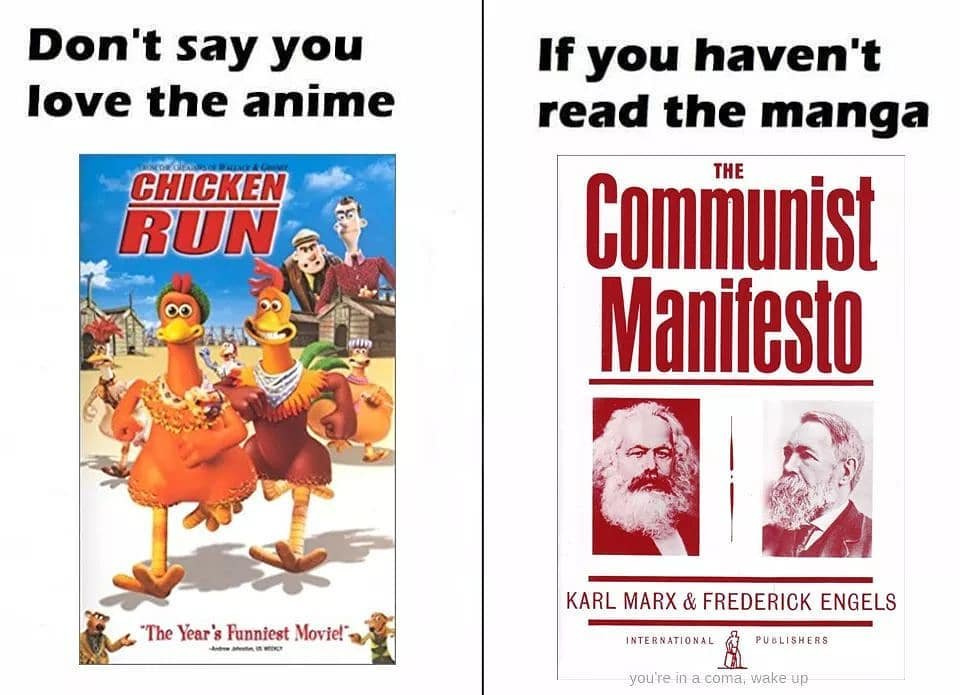

And yet, when I watch these documentaries, I cannot help but compare them unfavourably to the most successful British representation of a factory, one that foregrounds the almost carceral regimentation of working life. This interpretation shows how bosses encourage workers to see themselves as powerless individuals, rather than members of a collective. It reminds us that high-tech automation is rarely aimed at improving the lives of workers, but is more often introduced to combat falling profits. It is sceptical of the factory’s dehumanising and alienating effects, and of the dangers inherent in being managed by a computer programme.

This masterpiece also happens to be specifically about food production. It pays close attention to animal welfare, and can even be interpreted as a searing critique of factory farming. At times, it feels explicitly Marxist in its inspiration, suggesting that gradual reformism, or a reliance on bosses’ paternalism and goodwill, can never be the solution to a system that is exploitative at its very core.

I’m talking, of course, about Chicken Run, which achieved something that Gregg Wallace’s documentaries have not: a wildly successful representation of a food factory that is deeply political, and focused on workers and their lives. The choice between mainstream success and political relevance is clearly a false one, then: if a group of plasticine chickens can manage both, so can the BBC.

Credits

Sean Wyer is a Ph.D. candidate in Italian Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, and is usually based in London. He writes an occasional free Substack, and is on Twitter, Instagram, and email.

Sinjin Li is the moniker of Sing Yun Lee, a graphic designer and illustrator based in Essex, UK.

Sing Yun uses the character of Sinjin Li to explore ideas found in science fiction, fantasy and folklore in their personal work. They like to incorporate elements of this thinking in their commissioned work, creating illustrations and designs for subject matter including cultural heritage and belief, food, and poetry among others. Their work was shortlisted for the British Science Fiction Association (BSFA) Award for Best Artwork 2018 and 2020 respectively. They can be found at www.sinjinli.com and on Instagram at @sinjin_li

Many thanks to Sophie Whitehead for additional edits.

Additional Viewing

The Chicken Factory (BBC)

Inside The Factory (BBC)

Snackmasters (Channel 4)

Thanks - excellent piece

Food provenance quality & respect shouldn’t be confined to those consumers with adequate funds time or location, nor should it be for those working hard to provide it.

However

We all appreciate the can or the package that safely keeps fresh & affordable that which we might not have got or have been able to afford or had the time to prepare

Also

not all jobs of a monotonous nature need to be permanent and can often be temporary stopgaps to allow transition to more rewarding work or education if younger.

If they are though the only alternative at the time, then the following becomes even more important.

thus, with labour now being the more precious commodity than it was (because of covid and Brexit) it is imperative that Employers provide adequate remuneration and development where possible which nourishes the Employee and aids the Employer who then maybe does not need to be distracted by ever increasing staff turnover.

This has always been the case but may be the more now with fewer imported cheaper paid staff (one of those very hard to find brexit pluses perhaps but which of course further pushes up costs and inflation for poorer families in the interim)