Searching for Soursop

Giorgia Ambo traces the life of the elusive, capricious tropical fruit in the UK.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles. Each Monday we publish a different piece of writing related to food, whether it’s an essay, a dispatch, a polemic, a review, or even poetry. This week, Giorgia Ambo explores why soursop is so difficult to find in the UK and speaks with the people who devote themselves to making the tropical fruit more widely available.

If you wish to receive Vittles Recipes on Wednesday and Vittles Restaurants on Friday for £5 a month, or £45 a year, then please subscribe below – each subscription helps us pay writers fairly and gives you access to our entire back catalogue.

Searching for Soursop

Tracing the life of the elusive, capricious tropical fruit in the UK. Words by Giorgia Ambo. Photographs by Wunmi Onibudo.

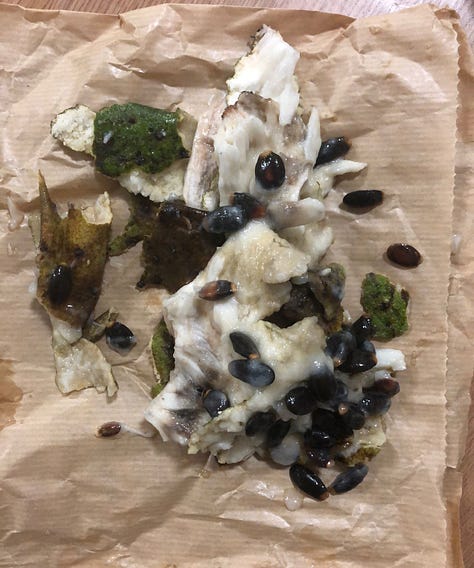

It’s almost 1am. I’m the only person awake in my South London flat, and just as well, because I’ve trashed the kitchen. Condensed milk and lime juice dribble across the countertops, and my hands are stained with powdered nutmeg. On the table is a soggy paper bag with shredded fruit skin on top, a worn-out chopping board, and a plastic container filled with seeds. Despite the late hour and the chaos surrounding me, I’ve not been drinking, and I’m not back from a night out. The evening has been spent doing something more exciting, something I’ve wanted to do for a long time: I’ve just made a soursop milkshake. To make it, I tore the soursop apart with my hands; despite its tough-looking exterior, the thin skin peeled off easily. The inside was bright white and had a citrusy flavour somewhere between strawberry and pineapple, but with a slippery, fleshy texture that tasted like neither. I only meant to try a few bites, but the fruit – pulpy and succulent, with seeds in every mouthful – was impossible to stop eating.

Soursop – also known as graviola or guanábana in Spanish-speaking countries – is a tropical fruit which is native to the Caribbean, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. The name misleads: beneath its prickly green exterior, the soursop’s white flesh is sweet and custard-like, only slightly acidic. Soursops from Sri Lanka tend to be about the size of a clenched fist, while soursops from Columbia and Ecuador can grow as large as a rugby ball, weighing in at 4–5 kilos. You’ll know when soursop is ripe, as the fruit becomes heavier, softer, and feels ready to ooze when you press your thumb against it.

Soursop juice is the most widely available form of the fruit in the UK; you might spot it in Asian corner shops, West Indian markets or, as I once did, on the shelves of T K Maxx. As someone with Dominican heritage, there was a cupboard shelf lined with cartons of the juice at home. ‘Grandma used to drink a cup of soursop juice every day. It stops cancer, you know!’, my dad would say as he swigged some down.

But as far as the fruit itself is concerned, unless you’re in the right place at the right time, have a good helping of determination, or simply ‘know a guy’, the chances of finding a soursop in Britain are slim. London is not short of exotic fruit and vegetables – a walk through East Street Market, Spitalfields, or Rye Lane will tell you that. But even as I see tonnes of plantain, papayas, mangoes, and yam, I have always wondered why my fruit is missing from the aisles (although one time I was catfished by a jackfruit in Brixton Village). One of the only times I have seen soursop at a small shop was outside a grocery in Camberwell, where it sat neglected: shrivelled, stale, and tinged black.

There are plenty of responses on Reddit about the fruit (‘Soursop is such an underrated fruit’, ‘Nothing quite like it! Even the name is cool’), so one day, I texted my Bajan friend, who was also raised in the UK: ‘Have you tried soursop?’ She immediately replied, ‘I have!!!’ but didn’t ‘remember it that well’. She then sent me an Afrobeats playlist she’d made called ‘Soursop’, which was over two hours long, its cover photo a picture of Gros Piton in St Lucia. I felt that kindred clawing feeling; she too was making a hazy collage of a half-lost home. There seemed to be something special at the pit of this thing, I thought. I was determined to find it somewhere, somehow.

As I looked at the supply chain of soursop in the UK, I found the retailer from which most of the fruit emanated – helpfully named Soursop UK – which operates from several warehouses in Essex. I had to see it to believe it, so one day I decided to go and witness the life of soursop in these uncanny British surroundings first-hand. I found Soursop UK down a winding country lane just outside of Billericay, on Oaklands Farm Industrial Estate. The farm is also home to My Exotic Fruit, and – as of August this year – The Greengrocer, a specialist shop offering tropical produce, from snakefruit to rambutan. Billericay, which is over 90% white, home to one of England’s oldest pubs and our beloved Gavin and Stacey, wouldn’t be the first place you’d expect to see soursop. But this is a fruit of unexpectedness, after all.

Soursop UK, My Exotic Fruit and The Greengrocer were all founded (and are all headed up) by Colin Bannell. Bannell created My Exotic Fruit in 2014, when he was twenty-two, after visiting Thailand for the first time (he’s been back to Southeast Asia thirteen times since, and is currently learning Vietnamese). ‘My eyes were opened to what’s out there: the sights, smells, tastes, shapes and colours of so many different kinds of fruit,’ Bannell told me. He has curated a wide range of soursop products, including pulp, juice, jam, tea, and powder, which can be cooked into dishes, or used to make drinks. (‘The powder is made from a mature, but not yet ripe fruit, ground down to a biscuit-like texture’, Bannell tells me.).

Walking around the store, Bannell explained that soursop’s absence from supermarket shelves in the UK is due to the fruit’s capriciousness. While tropical fruit like plantain can be transported by boat, which takes several weeks, soursop’s delicate ripening conditions mean the flesh is only good for a fixed time, so suppliers must instead rely on speedy air travel. When soursop is collected from the airport in the winter, it goes under special blankets to keep it at a certain temperature, ideally between 15 and 20°C. Bannell’s shop, which is attached to one of the warehouses, is lined with wall-to-wall fridges, but soursop – ever the diva – must sit on a high shelf, protected from the refrigerator’s unforgiving cold, which would make its flesh brownish and hard and render the fruit inedible.

Soursop UK was initially sourcing its fruit from St Lucia, but recently switched to using a modest family-run business in Sri Lanka, which was suggested to them by a native friend. Shipments come in twice a week, about 400–500 soursops in total. Some of these soursops remain in store, but most are sent to customers who have ordered online. The fruits are sorted and packed on-site in the Billericay warehouse, then posted to individual customers, plus a demanding new client – one of the country’s leading luxury department stores. (The details of this operation are still under wraps).

This elaborate process naturally drives up the fruit’s cost. Before purchasing my first soursop in April this year, I had never dreamed of paying £11 for a single piece of fruit. (For context, just one extra pound could buy you M&S’ large fresh fruit bundle, which includes a mango, three soft citrus, one orange, two plums, three pears, three Pink Lady apples, and 200g of grapes.) With the high cost in mind, Bannell initially started the business with a mobile bar, using his bartending experience to make tropical fruit cocktails. It was the sheer demand from his customers, who liked soursop drinks so much that they wanted to try the fruit, that encouraged him to start Soursop UK in 2016. According to him, Soursop UK had two types of online customers: ‘people wanting to reminisce and eat something from home, and those buying it for health benefits.’ (Among Caribbean and Asian communities, many people – like my late grandma – have held the belief that soursop cures cancer, but Cancer Research UK states there is not yet enough evidence to verify this. Still, it’s high in vitamin C and rich in antioxidants.) ‘For the local community in Billericay, an exotic fruit store is funny’, Bannell admits. ‘On the whole, people have been sort of mesmerised. They don’t know what to do with the fruit, particularly the older demographic. But that takes education.’ Later, I watch him spend time with each customer, giving recommendations according to their individual tastes.

Despite Bannell’s enthusiasm, soursop is still niche in the UK, with an estimated 60–70 tonnes imported per annum (by comparison, our mango imports in 2023 were at 82 thousand tonnes, while watermelon imports totalled 328 thousand tonnes). While you won’t spot soursop at your local Sainsbury’s, demand for the fruit has exploded over the last decade, serving as a gentle reminder that there is a thriving food culture outside the corporatised world of supermarkets. ‘Some people even fly specifically to get soursop from us and take it back home, both within the UK and … to their families abroad – mostly to Bangladesh,’ Bannell tells me.

If you need more proof of soursop’s popularity, turn to the 23,000-member Facebook group – started by Bannell – which is dedicated to promoting the fruit. The group is filled with questions and queries like, ‘Are dried soursop leaves supposed to be green or brown when making tea??’, ‘What infections can soursop treat?’, and, a favourite of mine, ‘How much soursop should one eat in a day?’ (to which one user replied, ‘As many as u can!’). Far from being a Soursop UK advertorial, the group is more like the Wild West of soursop vending, with posts ranging from those about produce purporting to cure pancreatitis to those selling soursop on the black market. Among the sellers, there are also good samaritans offering advice; one Nigerian farmer shared his YouTube video, which reveals how his humble potted tree produced more than eighty soursops and demonstrates how others could do the same. The group throws users from South Africa, New Zealand, Britain, Botswana, and Australia together to form a strange, international soursop family. ‘I started it on a whim,’ Bannell said, but now ‘hundreds of people join a day.’

Soursop UK, though the largest contemporary supplier in the country, is not the first of its kind. Tropifresh, a wholesaler in New Spitalfields Market, has been supplying soursop and other exotic fruit since 1983, when seventy-two-year-old Peter Durber and his wife Sandra (who is Jamaican) set up the business together. ‘It’s been part of what I call “back-home food” for migrants, especially West Indians, ever since they started to arrive in the UK,’ he said. He recalls that although soursop was available prior to the 1980s, this was ‘just a few kilos here and there’ at specialised West Indian food outlets.

At Durber’s shop, the clientele is more familiar with soursop than in Billericay; Tropifresh mostly supplies to greengrocers and other traders, with some buyers selling on to Latino and Caribbean restaurants. New Spitalfields is only open between midnight and 9am, and Durber also allows the general public to come in and buy the fruit, since soursop is hard to source. ‘We ask people when they’re going to eat it. Most people want to send it to a relative that won’t receive it for three or four days … then we know at what stage of ripeness to give it to them, so it doesn’t turn to pulpy mush’, he says. He tells me that in the Caribbean, soursop is the type of fruit that’s ‘grown in Mum and Dad’s back yard. They’re very small clusters of trees … not like large mango orchards’, which are planted on a large scale.

Half of Tropifresh’s soursop comes from the Caribbean (currently Jamaica, St Lucia, and Grenada), while the other half comes from Colombia, where the fruit is larger and slightly sourer in taste. In Latin America, production of soursop has been commercialised, but that’s not a high priority in countries like Jamaica, where the focus is much more firmly on tourism. Selling soursop across long distances is risky, particularly for smaller-scale farmers, since the region is prone to extreme weather and storms can often delay shipments. ‘Instead, they send produce to North America and Canada for a lower fee’, Durber says. Despite these challenges, Durber insists upon a supply of Caribbean soursop – the smaller and sweeter fruits are his preferred variety. ‘You really have to fight for Caribbean soursop, which we do’, he told me proudly.

Sarah Moore, who sources kilos of the fruit from Durber to make soursop ice cream on a Hertfordshire farm, tells me that she grew up with soursop in Trinidad, until she moved to the UK when she was ten years old. True to how things are done in the Caribbean, Moore’s ice cream is not mass-produced – there are 120 individual servings made in each run, packaged in small pots the size of those available at the cinema. The process is hugely labour intensive, Moore tells me; the fruit is peeled by hand and sieved two or three times at least. A traditional fresh custard base is used, with machinery only used during the churning process. ‘Back in Trinidad, we made soursop ice cream as a family, using those old churns where you throw the salt and the ice in,’ she says. Most of Sarah’s customers are Afro-Caribbean, placing orders at Christmas time for a ‘taste of home’. But Sarah also sells the ice cream at a farmer’s market in Hertfordshire, where it’s loved by English customers too. ‘I tell them it’s similar to the palate of elderflower and pear, because it leaves a slight aftertaste on the back of your tongue’, she says. Sarah is mixed heritage, ‘fusing the two worlds of the Caribbean and the UK is important’ to her. Her ice cream is smooth and delicious, and we both agree this refined product feels distant from the delightfully messy experience of eating the ripe fruit itself.

In the UK today, so much of our relationship with food has become about convenience, so I suppose it makes sense that only the Caribbean foods considered ‘functional’ have seeped into mainstream British life. You can pick up a curry goat patty on your commute to work, or even buy a spicy jerk chicken ready-meal and serve it up in ten minutes. But hunting down a soursop, selecting the perfect one, figuring out where the hell you’re going to store it, waiting for it to ripen, and getting your hands sticky and slimy in the process, doesn’t scream ‘sellable’ – at least, not for a Western market – and so the fruit remains non-incentivised. Bannell summarises the predicament of trying to sell soursop: ‘From a commercial standpoint, it’s much easier to lose money than it is to generate profit [with soursop], because you can lose one, two, or three thousand pounds in a shipment.’ This is possibly why many immigrant run small businesses cannot take the kind of risks that Bannell does.

Even so, the soursop community keeps the fruit circulating within the UK. Durber’s market supplies to RAYA Grocery, where I got my first soursop. RAYA is a specialist Southeast Asian store at Borough Market, owned by husband and wife duo Michael and Worawan Kamann. Worawan, who was born in Thailand, had always been familiar with soursop, but Michael discovered it by chance. The Kamanns reflect the two distinct categories of their customer base: those who know and those who come to know, both equally loyal to this fruit they love.

As I talked to more people about soursop, I began to think that perhaps the small-scale, slow cycle of the fruit was not such a bad thing. When I decided to make my milkshake, I was forced to sit with the fruit, searching for and eventually finding sweetness beneath the surface. I can’t say the same for most other food I consume. When I purchased my first soursop at RAYA, I saw the fruit’s novelty unfolding in real time, as a group of American tourists passed the store in awe. ‘Oh my God, look! All your exotic fruit right here!’, one said. ‘What the hell is a soursop?’ her friend shouted back. I hoped the sign that read, ‘Do not squeeze you WILL be charged!’, propped up against the soursop, would give them a clue.

Credits

Giorgia Ambo is a British journalist, covering culture and lifestyle. You can find more of her work here, or follow @giorgiaambo on Twitter to slip into her stream of consciousness.

Wunmi Onibudo is a photographer based in London whose work reflects human stories and modern culture. You can find her at www.wunmio.com or on her Instagram at @wunmio.

The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

I always thought soursop and custard apple (which I love) are the same. Reading this has made be crave the fruit and now I am on a mission to try the elusive soursop for myself!

I think I have eaten soursop as Coração de Boi in Mozambique. Very delicious but I hadn't thought about the supply chain implications of eating it in the UK. Thank you for this insightful and beautifully written piece.