So much more than ‘Britain in the sun’

‘Do you feel more British or Spanish?’. Stefan Williamson Fa writes about Gibraltarian cuisine. Photographs by Stefano Blanca Sciacaluga.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles! In today’s essay, Stefan Williamson Fa writes about how Gibraltar’s cuisine is multifarious and evolving. despite the commonly reductive portrayal of the strait’s foods and people.

Issue 2 of our print magazine, on the theme of Bad Food, is still available. You can order a copy below

In June last year, almost ten years after the Brexit referendum, the UK and the EU finally agreed to resolve one of the last outstanding issues of post-Brexit relations: Gibraltar. Despite 96% of Gibraltarians voting to remain in the European Union, the territory – which shares a land border with Spain – was pulled from Europe. With Brexit long out of the media spotlight, news of the imminent treaty barely made headlines. For the 38,000 Gibraltarians on the Rock, however, it was deeply consequential, raising urgent questions about the future of food provisions, labour and identity.

One of the few outlets to cover the story was GB News, which offered brief, patronising interviews with local politicians. Nigel Farage and Jacob Rees-Mogg accused Gibraltar of ‘wanting to have their cake and eat it,’ implying that if the strait’s people were truly British, they should reject any cooperation with the EU and Spain. Once again, a binary choice was imposed: British or Spanish, one or the other. This lens is familiar to anyone from Gibraltar. Even before I tell people where I am from, I can sense the confusion as they try to place my name, my appearance and my accent. When I explain that I was born in Gibraltar and that I only identify as being Gibraltarian – or Llanito, as we call ourselves – the inevitable follow-ups arrive: ‘Do you feel more British or Spanish?’ ‘Do you speak English or Spanish?’

These are simple questions with complicated answers. In a world that still expects national identities to be neat and legible, a not-quite-former colony in Europe creates confusion. Gibraltar is now officially a ‘British Overseas Territory’, yet we have our own ‘national’ football team, a tiny population and a mixed heritage that doesn’t fit easily into the categories with which outsiders are familiar. Explaining who we are often requires more context than most people expect – or have the patience – to hear.

The civilian population of Gibraltar has always been diverse, multilingual and multi-faith – far from an exclusive enclave of ‘expats’ from Britain. When I moved to the UK as a student over fifteen years ago, I was surprised by how often Gibraltar was described as ‘Britain in the sun’ – a phrase that didn’t resonate with my own upbringing. People I met who had visited Gibraltar on day trips from the Costa del Sol spoke of red phone boxes, custodian-helmeted police and fish and chips. To me, the helmets looked like sweat traps in summer, the phone boxes didn’t work and … fish and chips? I’d never even eaten them as a child.

While I did grow up eating fish, this took the form of bright yellow stews, grilled sardines and platters of fried seafood piled high with boquerones (anchovies), puntillitas (baby squid), cazón en adobo (marinated dogfish) and rosada (pink cusk-eel). There were chips, yes, but fried in olive oil, not served with battered cod. Yet in Gibraltar today, ‘fish and chips’ dominate the menus along Main Street (also known as Calle Real, the pedestrianised thoroughfare at the heart of Gibraltar). On my most recent visit, I counted no fewer than twenty-seven outlets offering fish and chips along the roughly kilometre-long stretch, catering to tourists seeking a taste of ‘Britain in the sun’.

The Google reviews for Roy’s Fish and Chips – one of the two fish and chips restaurants at Casemates Square in the northern end of Main Street – end up debating Britishness as well as flavour. One reviewer is surprised: ‘It’s a shock that I’ve had to come to Gibraltar to find the best British fish and chips,’ while another insists that ‘anyone British eating this will be disappointed’. There are even complaints about the linguistic performance of staff, with one reviewer lamenting, ‘the waiter couldn’t speak english and couldn’t understand our order. sad to see the standard this low for british style fish and chips.’ Further south, at Piccadilly Garden Bar, a street sign splits the difference, with one side proclaiming ‘Traditional Homemade Fish & Chips’ – complete with Union Jack – while the other advertises ‘Hay Callos’, the rich chickpea and tripe stew whose best-known version hails from Madrid. Outsiders may see Gibraltarian cuisine as they see the referendum – British or Spanish – but for locals, it’s a reminder of the reductive binaries we are constantly asked to navigate.

Perched at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, Gibraltar has long been a strategic fortress for its numerous rulers (Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, Visigoths, Muslim dynasties and the Crown of Castile), controlling access to the Mediterranean. Britain seized Gibraltar in 1704, during the War of the Spanish Succession, and it fully ceded in the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht. This fit squarely within Britain’s expanding maritime-imperial project: a chain of ports positioned to protect trade routes, project naval power and circulate goods for profit.

In the decades that followed, the civilian population became a patchwork of migrants from across the Western Mediterranean – Genoese, Maltese, Minorcans, Catalans, Andalusians, Portuguese, and Sephardic Jewish and Muslim merchants from North Africa, alongside a few British and Irish settlers. In the late nineteenth century, following the opening of the Suez Canal, Sindhi merchants from the Indian subcontinent established shops in Gibraltar, expanding their trade networks and adding yet another layer to the mix.

Spanish soon became the lingua franca of this fledgling community, while knowledge of the English language allowed some to act as intermediaries between civilians and the colonial authorities. In addition to trade, civilians provided essential labour in the dockyards and in service of the garrison, without which the British could not have fully benefitted from the port. At the same time, the need to survive pushed parts of the community toward informal and illicit economies, including smuggling goods such as coffee and tobacco into Spain.

This diverse population shaped Gibraltar’s cuisine, within the constraints of its foodscape. With little land for agriculture (due to the Rock’s size and colonial restrictions) and limited access to fresh produce, the burgeoning communities adapted recipes using ingredients from Spain, Morocco and the sea. Dishes now considered quintessentially Gibraltarian reflect this diversity: Genoese-inspired torta de acelgas, a garlicky chard and cheese pie in an olive-oil-based shortcrust pastry; menestra, a vegetable and pasta soup with the characteristic flavours of kohlrabi and basil; and rellenos of all sorts – courgettes, long green peppers, squid or anchovies, stuffed with a mix of egg, cheese, garlic, breadcrumbs and the signature hint of marjoram.

Rosto – slow-cooked beef in a tomato sauce, with carrots and penne pasta simmered in the sauce – is ubiquitous, though was never really my favourite. On the other hand, I loved rolitos, a dish said to have originated in Malta. These small rolls of thin beef slices encase a stuffing of chopped olives, boiled eggs, bacon or ham, all held together with a toothpick and braised in a sauce made from the usual refrito and white wine. However, it is so time-consuming to prepare that it wasn’t something we had often growing up.

The South Asian influence also remains. Some of Gibraltar’s first public eateries were opened by families from the subcontinent, and for decades the most popular sandwich in town has been the chicken tikka bollo (roll) from Ramsons, a Gibraltarian Sindhi-run supermarket that has sold spices and foodstuffs since 1975.

And then there is calentita, the descendant of farinata. A thin, oven-baked dish made from chickpea flour, olive oil and water, it is somewhere between a pancake and a flan – firm on the bottom, creamy in the middle and crisp on top. Once hawked on trays by street vendors, calentita is now celebrated as our ‘national dish’, with an annual food festival named in its honour – although the dish is hard to find in Gibraltar today. If you want to try calentita, the best option is across the Strait in Tangier, where it is still served as a street snack. Vendors slice portions according to the number of dirhams offered, slap them onto paper, and sprinkle with cumin if requested. Versions of the dish under different cognate names (kalinti in Morocco and karantika, calentica or garantita in Algeria) are found in other port cities along the North African coast, reflecting histories of migration and cultural connections across the Strait. Whenever I’m craving it myself, I head to Algerian cafes in London, where a slice of warm karantika tucked into a baguette with harissa brings a variation on a taste of home.

The baseline running through most Gibraltarians’ diets, however, is largely Andalusian, understandably given the history of intermarriage and the social porosity of the border with Spain. Like many others of my generation, I had a grandmother who was born in a rural village in Andalusia and migrated to Gibraltar in the 1930s, seeking work and survival while the civil war raged in Spain. Weekly lunches at my abuelos’ house included rotating potajes – hearty stews of legumes, lentils, chickpeas or beans, and vegetables with prized nuggets of chorizo and morcilla. Puchero – a deeply savoury chicken broth, flavoured with salted pork ribs, beef, chickpeas and vermicelli – was a winter staple, while cold gazpacho accompanied fried fish or yellow rice with chicken or pork in summer. My maternal grandmother, born in northern Morocco to a Gibraltarian mother of Genoese descent, added chicken, seven-vegetable couscous and harira to this eclectic diet.

Two events in the twentieth century profoundly reshaped Gibraltarian identity and foodways. In 1940, during World War II, the entire civilian population was evacuated so the British military could fortify Gibraltar and ward off a planned German invasion. Families were scattered to Jamaica, Madeira, London and Northern Ireland, where they were housed in hotels or evacuation camps. What was supposed to be temporary dragged on for nearly a decade. In London, Gibraltarians like my grandmother endured the Blitz of 1940–41, struggling with the language and facing severe food shortages caused by wartime rationing. The British government’s broader strategy – prioritising military needs while imposing austerity across the empire – meant that many were left in similarly vulnerable situations.

Finding familiar ingredients in their temporary homes was a constant struggle: olive oil was sold in pharmacies to treat earaches, while squid and cuttlefish were tossed to cats. When Gibraltarian citizens returned home, they had acquired new tastes through exposure to dishes like Irish stew, bread-and-butter pudding and shepherd’s pie, though all were quickly reworked at home to suit local ingredients and palates. I still remember the shock of eating shepherd’s pie in Britain for the first time – bland and joyless without the chopped boiled egg, pimentón and green olives that my mother and grandmother always snuck into the filling.

Then, in 1969, General Franco closed the land border with Spain, cutting Gibraltar off for more than thirteen years. Overnight, families found themselves divided: with loved ones just a few miles away but separated by a wire fence, they were able to wave but not to embrace them. For many, loyalty to Britain (however complicated that was) seemed far preferable to living under a fascist regime, leading us to reorient culturally – including modifications to our cuisine.

With Spain shut off, Morocco became the territory’s pantry. Ferries from Tangier brought not just crates of fruit and vegetables but also a steady stream of labourers who worked in the dockyards, hotels and construction sites. Many stayed on even after the frontier blockade was lifted, establishing families and opening small eateries, butcher shops and grocery stores that, over time, became fixtures of the local foodscape. These shops still line Gibraltar’s side streets, their displays of fresh fruit and vegetables offering a welcome contrast to the duty-free electronics and jewellers that cater to tourists and dominate the main thoroughfares.

Gibraltarians, and the food we eat, are products of these historical, geographical and political forces. We are the result of the British colonial presence in the region, yet we are not from the British Isles. With limited resources, under pressure and throughout constant change, we have playfully made the most of what has been available, reimagining familiar tastes and forging a distinctive hybrid culinary identity from what we could find.

One of the clearest legacies of Gibraltar’s historical sieges and upheavals is an enduring fondness for preserved and long-life foods. Alongside canned evaporated milk, export-only Vimto and Dutch Edam cheese (queso de bola, the red-waxed ‘ball cheese’), tinned corned beef has achieved near-mythic status. In the 2024 ‘Our Gibraltar’ art competition, the winning piece, ‘Always a Part of Us’ by local artist Derek Duarte, depicted a humble tin of Hereford Corned Beef. For Derek, the corned beef symbolised ‘the old Llanito days,’ when scarcity demanded creativity. Once a necessity, carne conbí still appears in croquettes, or fried with potatoes and cabbage on weeknight dinner tables. I sometimes think Gibraltar must have the highest per-capita consumption of corned beef in the world. Even after Brexit disrupted supply chains, towers of tins could still be found stacked in Morrisons (the chain’s only branch outside the UK, and its most profitable) or in Eroski, the Spanish supermarket that, uniquely, also carries Waitrose products.

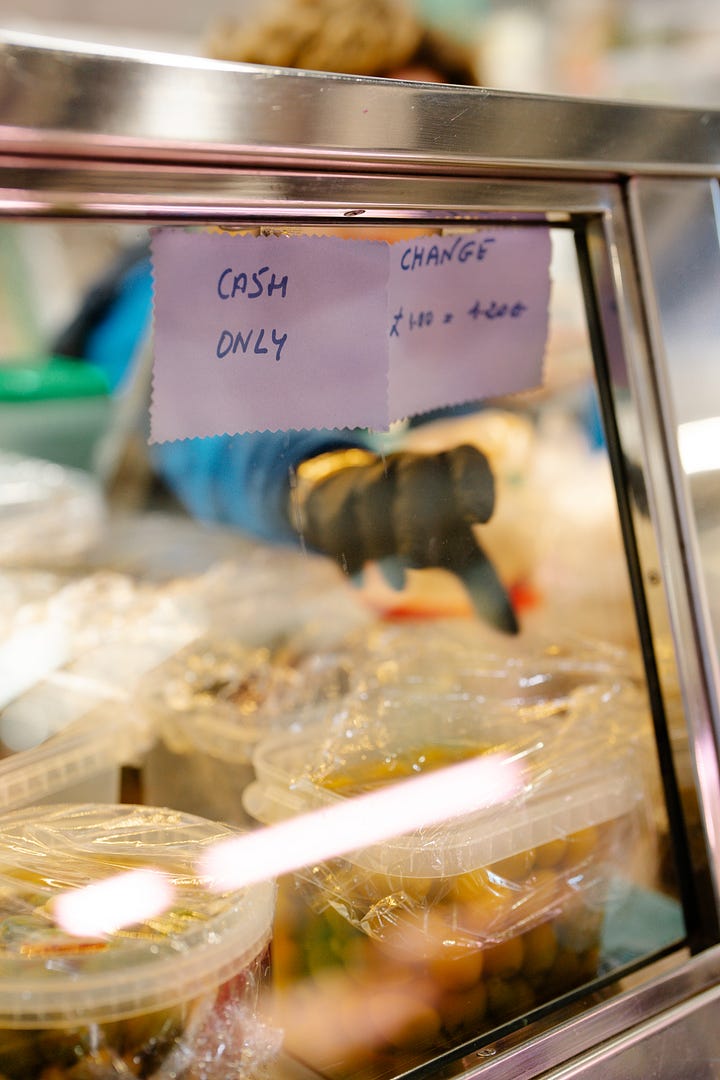

So, if you are a day-tripper, step off Main Street and you’ll find glimpses through the cracks of the ‘Britain in the sun’ façade. At Tasty Bite, a family-run takeaway on Tuckey’s Lane (also known locally as Callejón del Jarro, or ‘Beer Mug Lane’), Francis Sene lays out trays of calentita, torta de acelgas, cuttlefish, chickpea and tripe stews, stuffed anchovies, corned beef croquettes, homemade sausage rolls, Cornish pasties and Spanish tortilla. ‘Soon we might lose all these dishes,’ Francis tells me. ‘Young people come because it tastes like their grandparents’ cooking, but they don’t know how to make it themselves.’ There’s a sense that this mix of foods that makes up our diet and reflects our history is slipping away, unsuited as it is to the pace of modern life – and certainly not the stuff of TikTok trends. When I ask Francis which dish he is most proud of, he doesn’t hesitate: pudin de pan, his version of a bread pudding. ‘Nobody makes it like this. I’ve tried bread-and-butter pudding in England, and it’s nothing like this. They don’t do it in Spain, either!’

The pudin – dense, cinnamon-scented bread soaked in milk and baked until set, with a few raisins in the mix – is a fitting metaphor for Gibraltar itself: not Spanish, not British, not purely Mediterranean, but something stubbornly in-between. Like our food, our identity isn’t a choice between Union Jack or Spanish flag, fish and chips or callos. It is hybrid, awkward, sometimes unglamorous but uniquely Gibraltarian. The world prefers neat categories, yet we live in the cracks, cooking and eating in that specific, liminal space. No matter the political divides or the pressure to choose, we continue to adapt, to cook and to eat outside neat categories, on our own terms.

We have our pudin and we eat it, too.

Credits

Stefan Williamson Fa is a Gibraltarian anthropologist based in London who researches and writes about sound/music, food, and religion.

Stefano Blanca Sciacaluga is a multidisciplinary artist, writer and musician from Gibraltar. His practice is deeply entrenched in photography and graphic design with regular forays into other disciplines, drawing inspiration from often overlooked details of the everyday and the layered cultural heritage of Gibraltar. You can find his work at www.stefanoblanca.com and @stefanoblancasciacaluga on Instagram.

The Vittles masthead can be viewed here.

Great stuff about a part of the world that seems to never get attention!

Now I'm hungry. It rather reminds me of the occasional hybrid foods I have had from West African and Brazilian friends.