Still Hungry: Skipping Breakfast and Flipping Tables in Lesbian Fiction

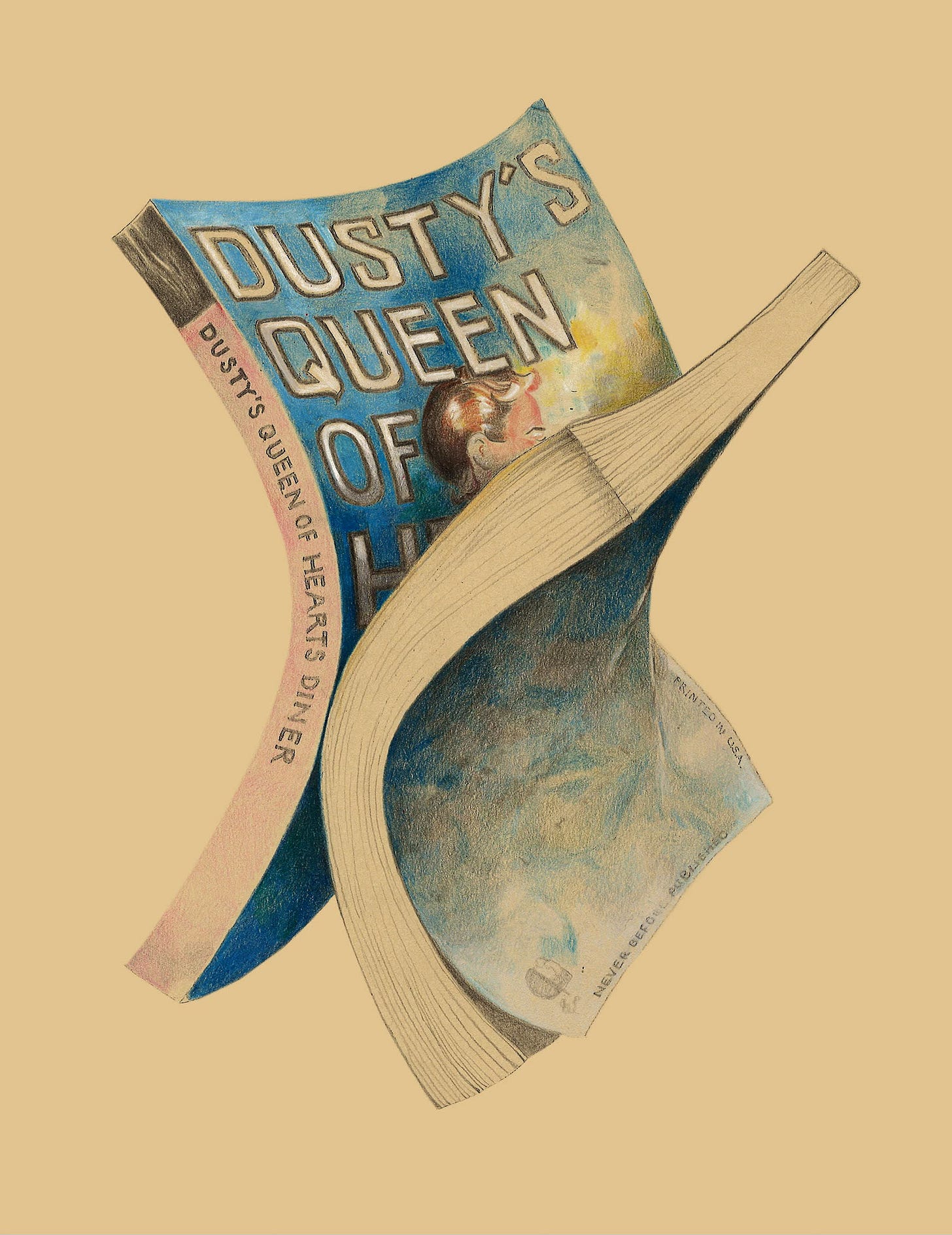

The riotous history of food in the lesbian feminist publishing movement. Words by Hannah Levene. Illustration by Catrin Morgan.

Good morning, and welcome to Vittles! Today, novelist Hannah Levene shares a playful hybrid creative–critical essay on the role of food in the lesbian feminist publishing movement.

We are still taking pre-orders for our first print magazine through our website if you’re in the UK or the USA – at a discount price of £18. If you subscribe to Vittles for £7/month or £59/year, you can access an extra discount and get the magazine for just £16.

We are also excited to announce that we now have distribution worldwide via Antenne Books, which means that the magazine will be available upon release via bookshops. For trade orders, both in the UK and abroad, please email maxine@antennebooks.com and mia@antennebooks.com (or harass your local bookshop into ordering some copies!).

Still Hungry: Skipping Breakfast and Flipping Tables in Lesbian Fiction

The riotous history of food in the lesbian feminist publishing movement. Words by Hannah Levene. Illustration by Catrin Morgan.

In Tasting Life Twice: Literary Lesbian Fiction by New American Authors, editor E J Levy writes, ‘Dorothy Allison once joked that the phrase “lesbian fiction” brought to her mind an image of two female books in love.’

[Scene 1: Lonely Lesbian smushes her lesbian books together like Barbies. One of these books is butch. Its dust jacket is leather, and it’s the right thickness for clobbering someone over the head with or hollowing out to hide your gun in. Lonely Lesbian does the voices.]

Book 1: Read me! Oh, when will I ever be read!

Book 2: I will read you!

[Swoon. Smush smush smush.]

For context, this pair of lesbian books – and hundreds more like them – were authored, printed, and distributed by an ascendant lesbian-feminist publishing movement in the USA and the UK, whose peak stretched from the 1970s into the 1990s. Though the production of the lesbian book – by publishers including Persephone Press, Diana, Naiad, Spinsters Ink, Daughters Inc, Firebrand Books, Cleis, Kitchen Table Press, and Virago – was bountiful, the hollow-legged hunger of the lesbian reader for printed lesbian matter would prove insatiable. What was once a rumbling in the stomach slaked only by ‘foraging through secondhand bookstores … for traces of the paper lesbian’1 transformed post-women’s-liberation-movement-meets-greased-up Gestetner into a great banquet of lesbian-book-filled bookshops.

Often, the fictional lesbian was just as much of a voracious reader as her readers. Meet Dusty of Dusty’s Queen of Hearts Diner (1987, Lee Lynch), the dashing butch cook who sets up a diner with her partner, the high-femme waitress Elly. Dusty remembers being a kid in the diner her parents used to run: ‘After hugs, milk, pie from the waitresses, a wink from the cook who’d worked with my dad, I might dash to the library … and return with a stack of books which I’d stash in my corner to devour, one by one.’ In a novel all about a diner, the cook is devouring books.

Or meet Nicky in Frankie Hucklenbroich’s A Crystal Diary (1997), the secret bookworm-butch who encounters fiction-femme Diane one night at the bar, and whose hunger is redirected into book-fuelled desire. Diane, the bartender tells everyone, ‘sits by the jukebox – I mean right by it – so she can get enough light to read by. Whole place is jumpin’ and there she is. Readin’.’ Nicky, who’s been hiding paperbacks in her bag while life buffets her about, licks her lips at the thought. She asks Diane out.

[Scene 2: Lonely Lesbian holds the butch book in one hand and the femme book in the other. Rolled up, the femme book is also good for clobbering and its dust jacket fits just right. Lonely Lesbian has used her stack of bar novels to make a bar, and props the butch book up against it. She does the voices:]

‘Who is this? I thought. Out loud of course I had to say Look lets go for breakfast and talk about books. You can explain honesty to me. Or ignorance. Alright?

We stared at each other. She said I’m reading Steppenwolf. Also The Duino Elegies. Do you know who Rilke is?

I nodded and I saw her smile for the first time. The next thing she said was Good. We’ll skip breakfast. What I really want to do is take a shower with you.

Right then I knew I was a goner.’

Nicky and Diane skip breakfast.

Or meet biomythographical Audre Lorde, whose body in Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982) becomes book. ‘When I came home from work with my arms full of the latest books and my mouth full of stories, sometimes there was food cooked, and sometimes there was not.’ Biomythographical Audre’s mouth is always full of stories, but only sometimes full of food.

Hunger is the frame for the writing, reading, and critique of lesbian fiction, as if all of these practices are happening inside a wide-open mouth. Two years before Zami was published, Lorde co-founded Kitchen Table Press with Barbara Smith. The name was chosen, Smith explained, because ‘the kitchen is the center of the home, the place where women in particular work and communicate with each other. We also wanted to convey the fact that we are a kitchen table, grass roots operation, begun and kept alive by women who cannot rely on inheritances or other benefits of class privilege to do the work we need to do.’

The kitchen table is a symbol, a place where hungry people meet to talk, to plan, and to organise. But what about to eat? It isn’t that eating is discouraged in lesbian print culture, but food in these works has a different relationship to the table. There’s no orderly breakfast, lunch, and dinner: these characters eat when they’re good and ready. There’s the odd cup of coffee, maybe a smattering of cheeseburgers. When food is cooked, often it’s to show something, the table set for a performance of some rare feeling like tenderness or safety. Like in Stone Butch Blues (1993), in which Leslie Feinberg’s protagonist Jess Goldberg bonds with their neighbour Ruth, a trans-femme domestic goddess, over the kitchen table. Ruth serves Jess stewed rhubarb with brown sugar, and after Jess finishes their spoonful, they say, ‘I had forgotten about taste.’

In A Crystal Diary, Nicky orders fries with a side of roquefort for dipping and the waitress seems to know the order, like she’s regular. Nicky is a cafeteria barfly. Her life is scattered and chaotic but, all over the place, Nicky is at the cafeteria. After a while, Hucklenbroich doesn’t even set the scene, just slips in a Coke picked up ‘from the green Formica between us’. Why we read voraciously might not be a mystery, but we would be remiss not to interrogate this cafeteria space (between us). If the kitchen table is set for the transference of something femme to something butch, what is the green Formica table set for? What does the cafeteria space allow into lesbian fiction?

[Scene 3: Lonely Lesbian saves up for a new book with a green Formica cover, props her lesbian books in scenes around it. Leaves the scenes set up ’round the clock.]

In her essay ‘The Butch as Drag Artiste: Greenwich Village in the Roaring Forties’, Lisa E Davis writes ‘(Closing time was 4 am, when everybody went around to Reuben’s, the people who invented the sandwich, on East 58th Street, just off Fifth, with the after-hours crowd, or up to Harlem.)’. Davis focuses on the ‘nightclubs operating under the protection of the New York mob’, with their ‘floorshows with dykes and gay boys (as they said back then) performing in drag’, but it is the parenthetical world of Reuben’s that interests me.

Who are the ‘after-hours crowd’? We can find them in A Crystal Diary, at a joint called Coffee Dan’s ‘where all the gays go after the bars close’ and where Nicky heads when she ‘badly want[s] a Coke, a cheeseburger or a piece of pie, something to feed the butterflies in my stomach and calm them down’. (Note: it’s not herself that she’s feeding, but the butterflies in her stomach.) And we can find them at Nicky’s very own cafeteria, when she manages to wheel and deal her way into owning ‘a defunct diner right next door to the biggest gay bar in Denver’. Nicky’s place

‘was open twenty-four hours a day. By day it was a very respectable little downtown working stiff’s lunch joint. In the evenings we got a mixed gay/straight crowd from the nearby bars and movie house. At 2 am, we got the bar rush from the gay joint next door. All day and night we could count on somebody … to be in for a soup-and-sandwich or a slice of chocolate cake.’

All these joints! Stiff! Gay! And all these hours! Open ’round the clock, the cafeteria is a waiting room, one that holds all the time in the world.

‘Until I can meet her, I figure to kill time sitting with the gay boys in Coffee Dan’s.’ That’s Nicky again, but I like it decontextualised: ‘Until I can meet her’. This is a lesbian temporality – it is after-hours, not necessarily late night but outside time, off the clock and revolving instead around the desire to be able to meet her. Davis wrote it the wrong way round: the parenthesis should have been around the butch drag artiste bar scene, with the after-hours crowd at Reuben’s left open-ended.

Another of Nicky’s haunts is Pam-Pam’s, San Francisco, which has

‘red leatherette booths, and is open ’round the clock including all holidays. During the day, Pam-Pam’s is respectably, solidly family-and-shopper oriented, but about ten o’clock at night it is taken over by johns and hookers and the hookers’ pimps. The light from the windows spills across the sidewalk and the cabstand outside bustles all night long.’

Surely this is the model for Nicky’s own joint: the light from inside spills out into the night, cafeteria time interrupting straight old street time.

Meanwhile, on the East Coast, Joan Nestle writes of Pam Pam’s (unhyphenated in New York), where a before-hours crowd is killing time. Says Nestle in her essay ‘The Fem Question’ (1992):

‘At seventeen I hung out at Pam Pam’s on Sixth Avenue and Eighth Street in Greenwich Village with all the other femmes who were too young to get into the bars and too inexperienced to know how to forge an ID. We used this bare, tired coffee shop as a training ground, a meeting place to plan the night’s forays. Not just femmes – young butches were there too, from all the boroughs, taking time to comb their hair just the right way in the mirror beside the doorway.’

Nestle’s Pam Pam’s becomes PamPam’s (no space this time) in Lee Lynch’s The Swashbuckler (1985). ‘Frenchy’s smile was smug as they entered PamPam’s and looked for a booth. She stopped and narrowed her eyes as she looked around, half-posing, half-looking at the women scattered among the gay men. They found seats at the counter.’ Pam-Pam’s/Pam Pam’s/PamPam’s must be a chain restaurant, then, a chain that links cafeteria dykes coast to coast, half-posing, half-looking, soup-and-sandwich both.

One night, Frenchy’s lover Pam (just one Pam!) suggests going to a coffee shop before hitting the bars. Frenchy asks why.

‘For dessert!’ Pam declared.

‘I’m too full for dessert.’

‘Not for this, you aren’t. Ever had baklava?’

‘Sounds communist.’

It’s great writing, a four-panel comic strip nestled into the novel. Frenchy, in the role of Embarrassing Butch, hates being exposed to the beatniks, wants to be hidden in the bars where there are no communist-flavoured desserts; what a square. But Pam, in the role of Lesbian Feminist, wants Frenchy to change up her diet, to access through her stomach the type of liberation that Pam has already indulged in. It is an exemplary (Lee) Lynchian plot, in which politics come to the previously apolitical butch in feminist form only. To that I say: baloney! In the cafeteria, spectres of Marx are baked into the baklava.

A novel I look to as a butch forefather to dyke fiction, Bryher’s 1956 work Beowulf (originally titled Comrade Bulldog), takes us to The Warming Pan in London. The Warming Pan is owned by Angelina and Selina. Selina calls Angelina her partner, Angelina calls Selina her comrade, and no one calls Angelina and Selina lovers, though they are. At their shared home, Angelina has put red posters with Russian lettering on the walls. She wears a beret over her short-back-and-sides, goes to undivulged meetings, and calls the customers the ‘stupid bourgeoisie’. She ‘never worried about food’, despite running a cafeteria: ‘“I don’t care what I eat” was her favourite phrase; it left one so free and unencumbered to face the future.’

By contrast, when the radical reality of the cafeteria space in queer history is baked into the landscape of lesbian fiction by Lynch, she denies this radical potential. The cafeteria in Dusty’s Queen of Hearts Diner is a flop. Elly describes her vision for a diner at

‘the very center of the Valley, offering nourishment, warm welcome; a place known for its food and harmony, famous for the way it erased walls between people; where gays and straights, blacks and whites, poor and rich acted kindly toward one another. Dusty’s Queen of Hearts Diner, a home for the tired world.’

Alarm bells ring around words like ‘center’, like ‘harmony’, like ‘erased’. With the best intentions, the gayest thing about Dusty’s is the ‘cook and waitress combo’. The tension in the novel surrounds not people coming to delight in this special, but people who are set on its destruction. Dusty and Elly feel as comfortable in their own place as Frenchy does eating baklava. The riverbank the diner is built upon is constantly threatening to burst; the disgruntled ex-pot wash, closeted and hot in his tight blue jeans, lurks outside with his gang. Dusty tells us that, during the night, ‘Some bastard wrote QUEER OF HEARTS across the front of the diner’. I’d go to the Queer of Hearts Diner any time, day or night, but Dusty’s isn’t open ’round the clock.

The difference between Dusty’s and Nicky’s is night and day, soup-and-sandwich. At Nicky’s,

‘These daytime diners never even dream of the garish change that happened every night as soon as the stores shut down and the neons in the bars lit up and sliced the thickening dusk … At night, fires burned on street corners and gunshots exploded in sundry alleyways; by day, Girl Scouts came in to sell cookies and buy Cokes. I loved it.’

Nicky loved it, this imperfect utopia where the after-hours crowd are fed and are not on the streets and do not require harmony or the erasure of difference in order to coexist.

In Susan Stryker’s 2005 documentary Screaming Queens, Stryker cites the 1966 Compton’s Cafeteria Riot in San Francisco (one of a list of establishments that Nicky describes as ‘home’ in A Crystal Diary) as the ‘first known instance of collective militant queer resistance to police in United States history’. ‘There was tables turned over … All the sugar shakers went through the windows and the glass doors,’ contributor Amanda St Jaymes says. ‘I think I put a sugar shaker through one of those windows.’

This is what the Formica table is set for. I don’t want a new wave of queers to open cafeterias, but I am hungry for queer cafeteria fictions, where the radical potential of a lesbian life can be kept alive and in print. I’ll end on an idea for a novel [Lonely Lesbian notes it down]: A gang of queens who call themselves The Sugar Shakers chew the fat at an all-night diner where the air crackles with the leftovers of collective queer resistance ready to be reheated in an instant – ie hungry as ever. The first line introduces a high-femme waitress wearing a paper pinny, flipping the sign on the door which says ‘OPEN’ on both sides.

╯°□°)╯︵ ┻━┻

Credits

Hannah Levene is a writer living in Norwich. Her novel Greasepaint was published by Nightboat Books in 2024. She has a PhD in Creative Writing from the University of Roehampton exploring the composition of new butch literature. Various prose, poetry, and conversations have been published in LitHub, Bomb, Fruit Journal, Hotel, DATABLEED, Blackbox Manifold, and FENWOMEN. She is currently working on a collaborative novel with D Mortimer titled Abraham’s Bosom.

Catrin Morgan is Assistant Professor in Illustration at Parsons School of Design in Manhattan. She is an illustrator, artist, and designer whose practice is concerned with mathematical, architectural, and theoretical systems. Catrin has an MA in Communication Art and Design and a PhD in Visual Communication, both from the Royal College of Art. She lives in upstate New York with her chickens.

The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

Adams, Kate. (1998) Built Out of Books: Lesbian Energy and Feminist Ideology in Alternative Publishing. Journal of Homosexuality 34(3–4) pp113–41.