Stress ReLeith: Chicken in Tarragon and Cream Sauce

Gavin Cleaver details how cooking as a means of relieving anxiety led him to undertake an online professional qualification with Leiths School of Food and Wine alongside his full-time job.

Good morning, and welcome to Vittles! In today’s essay, Gavin Cleaver discusses the occasionally baffling experience of completing an online cooking qualification with Leiths.

Issue 1 of Vittles is available for order on our website. If you would like to stock it at your shop or restaurant, please order via our distributor Antenne Books by emailing maxine@antennebooks.com and mia@antennebooks.com.

My day job is in medical publishing and, back when the Covid pandemic hit in 2020, it rapidly took over my life. All day there was Covid, as I worked with colleagues to quickly publish and publicise research into the virus, and in the evenings there was Boris Johnson on TV, blithely ignoring said research. There was no escape. My mental health began to deteriorate. In response, I began to cook.

Pre-Covid, my partner had done most of the cooking, but my need for an outlet meant I took over entirely (which she was generally pretty pleased about, apart from when the food was late). Three-course meals on weekday evenings, meats curing in the fridge for future projects, the day-disrupting rhythm of making a dough, leaving it to rise, pushing it back, and leaving it to rise again. Anything to shut my brain off. I cooked all of Jubilee by Toni Tipton-Martin twice through (and revisited the gumbo section even more often). I should emphasise that it was only my partner and me in the flat. We did not need to cater for eight people every evening – but what else was there to do?

In time, I received treatment for anxiety, and things settled back to something approaching domestic normality. But in the aftermath of my cooking mania, I realised that I had got better at it. Where once I’d followed recipes with religious fervour, suddenly I had the ability – and confidence – to improvise, update, and improve.

As pleasant a development as this was, unfortunately I’m the type of person who thinks that his learning doesn’t really count without a qualification. After months of googling obscure ingredients, Leiths School of Food and Wine had found its way into my Instagram algorithm. At that time, my main point of reference for Leiths was Prue Leith (who founded the school in 1975, but hasn’t actually had much involvement since she sold it in 1993). I was also vaguely familiar with the flagship Leiths Culinary Diploma – the alumni of which include Henry Harris of Bouchon Racine and Matt Tebbutt of Saturday Kitchen fame – but alas, I did not have £32,950 to spare.

Something else caught my eye, though: in response to the pandemic, Leiths had started offering online courses that lasted six months and cost a much more attainable – although hardly insignificant – £1,000 (and the price included a free set of knives). Each of the twenty-six weeks of the course had a different theme, from simply ‘Egg’ to ‘Host a dinner party’ via ‘Brunch’ and ‘Jointing’, and work would be assessed weekly. Crucially, successful completion of the course earned you an official accreditation. Obviously, this wouldn’t be equivalent to the actual diploma, but who outside the food world would know the difference? I was sold. Finally, I would get the immediate approval from a professional my work clearly deserved!

Week one brought a cold shower of reality. Entitled ‘knife skills’, I had to master chopping and processing methods for nine types of vegetables, combine them into a well-presented stir-fry, and then use the offcuts (and 2kg of chicken carcasses that, presumably, I was supposed to have to hand) to make ten litres of chicken stock – all of this while still working a full-time job. From the outset, everything about the course screamed Cotswolds stone kitchen, Aga, and endless spare time and resources. There was a jolly hockey sticks vibe to the curriculum, which in essence involved producing a quintessentially English picnic every week – a vast array of tarts, salads and breads, whose spiritual home was clearly a gingham picnic blanket. The whole thing felt at odds with my small, poorly ventilated flat in Bermondsey, with its single cupboard for pans, baking trays, cake tins, mixing bowls, and waffle irons.

But by this point it was too late to get my money back, so I proceeded to very, very carefully chop a Nisa’s worth of vegetables at the slowest pace imaginable (I only had to submit photos for assessment, so the fact that I was absolutely shit at fast chopping was irrelevant). As tedious as the process initially seemed, I realised that I enjoyed properly julienning a carrot into uniform little cuboids. Similarly, although chicken stock the Leiths way took a full nine hours to make, the result was crystal-clear. The teacher was pleased. I was pleased. This might actually be good and worth my while! I thought.

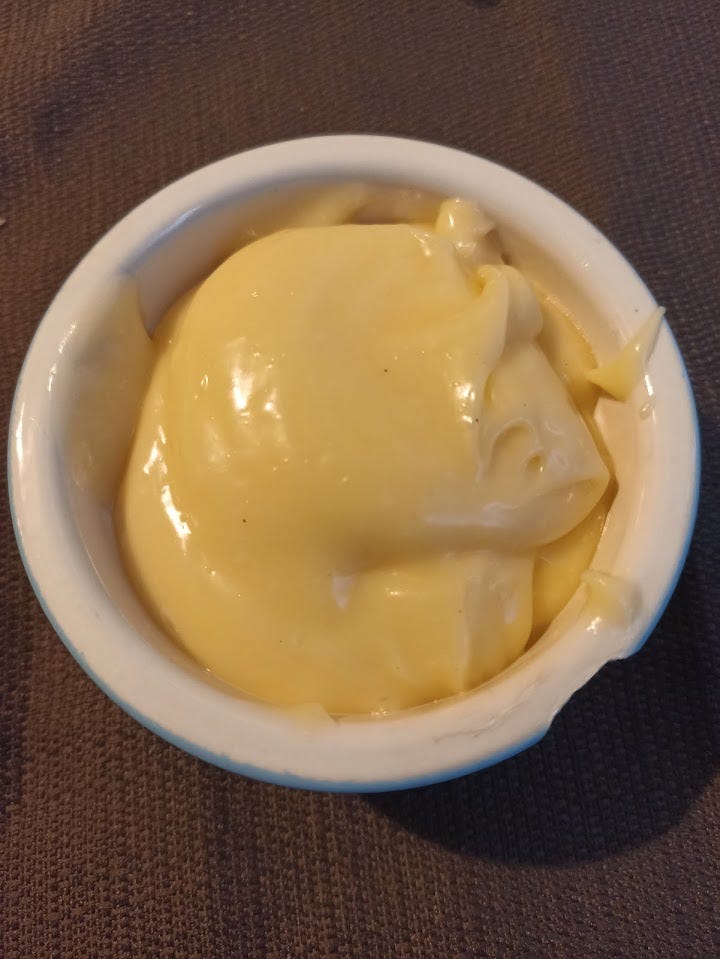

Then came egg week, which rapidly undid all the mental health gains I’d made. I’d sooner pay £50 for a small bottle of Heinz than ever again have to transfer oil onto an egg yolk via the tines of a fork to ensure only drips go through. Half an hour into this process, with an aching arm, my mayonnaise split. The response to the photo of the watery horror I submitted was: ‘Do it again.’ I was hanging on by a thread, and I could see that week three was ominously entitled ‘pastry’ (a week of collapsed choux would confirm that I had been right to worry).

I soon realised that Leiths was absolutely not messing around with this accredited qualification. Although some weeks it only took around three hours to watch the videos and try out the skills learned, others it took more than three times that, even before I accounted for repeating tasks when they didn’t work – which they often didn’t. The assigned course tutor appeared to have supernatural powers when judging the quality of my cooking, despite never eating a single bite – that, or she had hidden cameras in my flat. At one point I presented what I felt was a resolutely passable-looking eggs benedict, only to be told I’d messed up the hollandaise (my bain-marie was too hot) and had clearly tried to rescue it in a food processor. How could she possibly have known this from the photo? My phone is so old I often struggle to make out the faces of my loved ones in pictures I take.

After six months, the final exam loomed. All I was told was to set aside three hours and to buy a specific set of ingredients. It turned out to be a triple Bake Off-style technical challenge, in which Leiths remotely locked all recipe access and then tasked me with making a rosemary focaccia, a stir-fry, and the cursed mayonnaise – from scratch, with no instructions – and then uploading photos before the timer expired. My PhD viva was unquestionably less stressful, but somehow everything – even my personal Everest, the fucking mayonnaise – came together, and I passed (the photograph of the focaccia that I submitted cunningly obscured the slightly less browned side).

I’m relieved that the months-long slog is over, but I have to admit that I enjoyed myself – even if there’s no chance of my jacking it all in to cook for a living any time soon. And although in retrospect some aspects of the course seem odd – like the fact that grading via photograph couldn’t account for the actual flavour of an ugly-looking dish – the lessons I learned still resonate. Two years later, I still do most of the cooking at home, and while I’m no longer bashing out multi-course feasts on Tuesday evenings and insisting no one talk to me, I don’t find much joy in throwing a few jars together and calling it a day, either. I’m not necessarily painstakingly recreating the labour-intensive dishes from the Leiths repertoire that were deemed integral to the essentials of cooking, but I’ve reconfigured several of the recipes into easy weekday meals, and I make that stock whenever I roast a chicken. My versions are still fully delicious, but, crucially, they can be made extremely quickly, and they contain only a few ingredients.

One that I cook every week without fail is a take on a recipe from week five (‘Frying & Sauce’): chicken in a tarragon and cream sauce. I usually serve this dish with Tenderstem broccoli (using skills picked up in week four, ‘Vegetable Cooking’) and a quick caramelised red onion couscous (nothing to do with Leiths; just an easy, filling side), but it also works really well with a creamy mash. It requires a bit of multi-tasking, but can be ready in just over half an hour. I present it to you here so you can access its deliciousness without having a mental breakdown and spending a fortune on a cookery course.

Chicken in Tarragon and Cream Sauce with Caramelised Red Onion Couscous

Serves 2

Time 35 mins

Ingredients

2 tbsp butter

1 red onion, sliced

2 skin-on chicken supremes (see notes)

1 tbsp balsamic vinegar

750ml chicken stock (ideally homemade, but a stock pot is fine if you don’t have nine hours to spare)

200g Tenderstem broccoli

1 tbsp dried tarragon

100g couscous

salt

pepper

150ml double cream (see notes)

Method

Put two frying pans over a medium-high heat. Add 1 tbsp butter to each. Put the red onion into one pan and the chicken supremes, skin-side down, into the other.

Fry the onion for five mins until browned, then pour over the balsamic vinegar and fry for 1 min to caramelise. Take off the heat.

When the chicken skin has browned (which should take 10 mins or so), flip the supremes over and fry for 5 more mins. Pour about 500ml of the stock into the pan until they are mostly submerged but with the skin still uncovered. Bring to a boil, then reduce the heat to medium-low, add the tarragon, and partly cover the pan (Leiths tells you to make a cartouche, but using a lid or some foil instead isn’t going to ruin things), and poach the supremes in the stock for 10 mins.

Take one supreme out of the stock, then turn it upside down and cut it through the thickest part to see if it is cooked through. You should see uniform white throughout the inside – if you don’t, continue to poach both supremes for another few mins. When both are done, set the chicken aside and cover to keep them warm (use the cartouche if you made one, or else some foil).

Increase the heat to high. Cook the sauce down on a high simmer for 5 mins.

Meanwhile, trim the broccoli stalks, then cut the woody base from the broccoli at a 45-degree angle above the base – largely just to make it more aesthetically pleasing.

Add the remaining 250ml stock to a saucepan and bring to a boil. Place the couscous in a heatproof bowl. Season with 1 tsp salt and a few good grinds of pepper, then mix in the caramelised onions and pour over the boiling stock. Cover and set aside.

Add some water to the now-empty saucepan. Bring the water to a boil, then put the broccoli in a colander over the pan, cover, and leave to steam for a few mins until the stalks are tender (alternatively, you could fry the broccoli in some more butter).

Check on the tarragon and stock – it should have reduced by about half and be noticeably thicker. Remove from the heat, then pour the cream in slowly while mixing with a spoon. Once all the cream has been incorporated, put the sauce back over a low heat until it starts to bubble.

Serve the chicken supreme alongside the caramelised red onion couscous with the broccoli on the side. Pour plenty of the tarragon cream sauce over the chicken.

Notes

Leiths demands that you trim the wing meat off the supreme. I’m sure there’s a reason for that which will be re-explained to me in the comments section, but I just leave it.

The Leiths version of this recipe uses crème fraîche rather than cream, which I found more likely to split (although the resulting sauce does look prettier). You need to use high-fat cream – something like Elmlea will split straight away.

Credits

Gavin Cleaver is a former academic turned writer. He has worked at the Dallas Observer, The Grocer, and The Lancet, and has written for The Atlantic and Vittles.

This recipe was tested by Tamara Vos. The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

The online course was never an option, so I did the full blown one. Happy memories just flooded back reading this. Thanks, Louis

I so enjoyed this article. Made me chuckle right the way through and I feel Gavin and I would get on just fine. Keep going!