The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook: An Audacious Literary Experiment

Gertrude Stein's biographer Francesca Wade on how Alice B. Toklas expanded the genre of autobiography with a book of recipes. Illustration by Ella Bucknall.

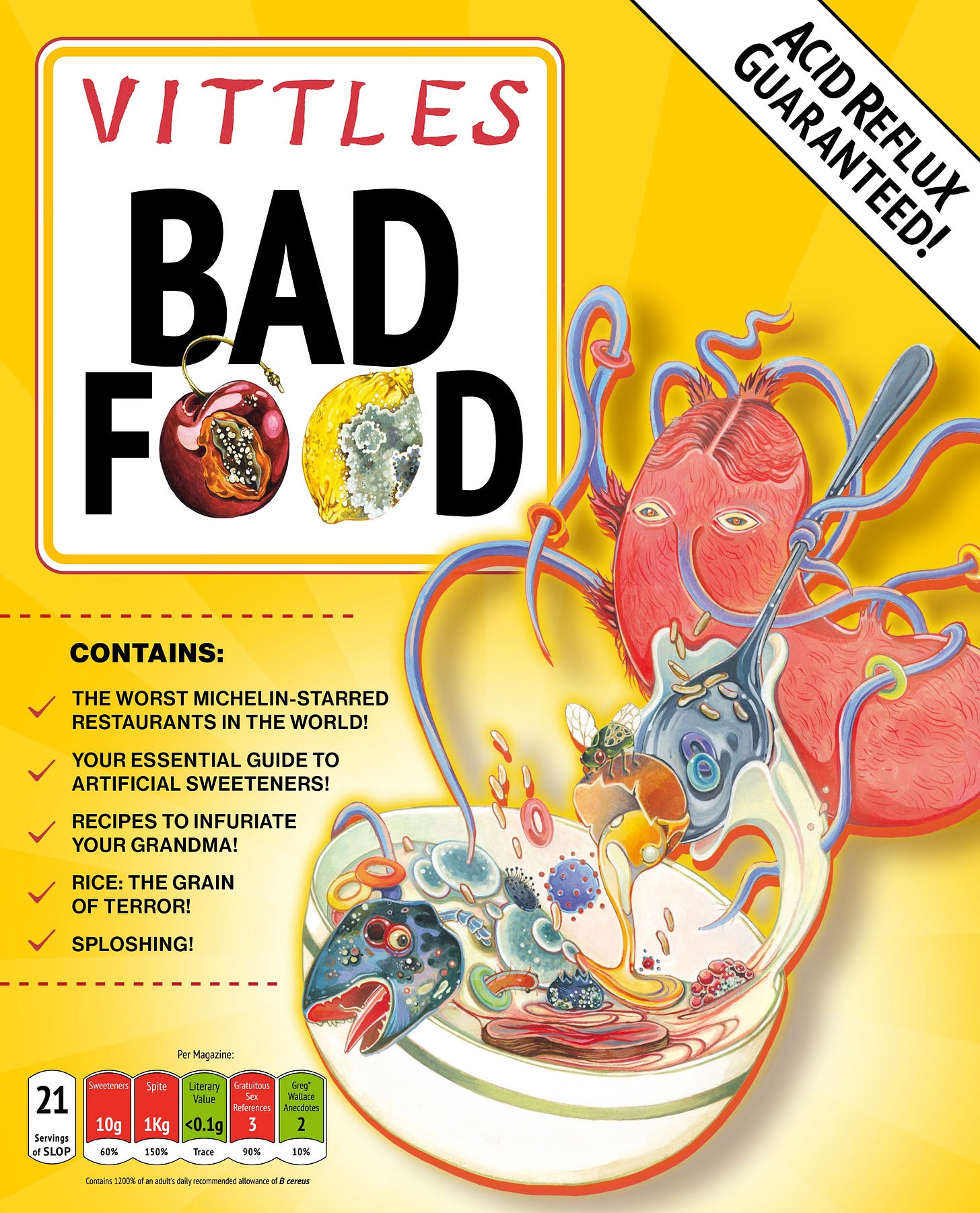

Good morning, and welcome to Vittles! Last week, we announced Issue 2 of our magazine – titled ‘Bad Food’ – which goes to print this week. We’re selling through the issue quickly, so if you wish to guarantee a copy, pre-order the magazine now. If you order before 1 December, you will receive it for a discounted price, with an extra discount for paid subscribers (see the original email for details).

In the summer of 1954, a beleaguered editor at the American publisher Harper & Brothers wearily drafted a telegram to the attorney general in Washington. He had been waiting months for Alice B. Toklas – the elderly widow of the writer and art collector Gertrude Stein – to send in the final pages of her well-overdue cookbook. Now, among the recipes that had finally arrived, was one that threatened to land the publisher in trouble. Its title was ‘Haschich Fudge’, and its ingredients included fruit, nuts, spices and Cannabis sativa. ‘This is the food of Paradise,’ proclaimed the accompanying text. ‘Euphoria and brilliant storms of laughter; ecstatic reveries and extension of one’s personality on several simultaneous planes are to be complacently expected.’ The attorney general, amused, replied that it was illegal to buy, sell, grow or indeed cook with marijuana leaves – but not to write about them. Erring on the safe side, the editor quietly cut the recipe from the manuscript. But his British counterpart let it through. When newspapers started to comment, delightedly, on the incongruous inclusion (some claiming it must offer a clue to Gertrude Stein’s avant-garde writing style), Toklas insisted she was not to blame: the recipe had been supplied to her by an artist friend, Brion Gysin, and she had no idea of the Latin name for marijuana. Friends told her no one would believe her innocence: she had pulled ‘the best publicity stunt of the year’. Her cookbook quickly became a bestseller, and the notoriety of her ‘hash brownies’ made Toklas an unlikely icon of 1960s counterculture (see the 1968 film I Love You, Alice B. Toklas, in which Peter Sellers stars as a lawyer who becomes a hippie after trying her recipe).

The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book remains a touchstone for personal, genre-bending food writing, built around a ‘mingling of recipe and reminiscence’, in Toklas’s words. Today, her name adorns celebrated restaurants, from Toklas in London to Alice B. in Palm Springs, and her work has been praised by cooks including James Beard, Alice Waters and M.F.K. Fisher (who described the cookbook as a ‘minor masterpiece’). But Toklas always insisted she was baffled by the book’s success, playing down the achievement with characteristic self-deprecation: ‘As if a cookbook had anything to do with writing.’

Yet The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book is, in many ways, an audacious literary experiment and an innovative form of autobiography. Toklas shot to international fame in 1933 after the publication of the bestselling Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, in which Stein adopted her partner’s voice to tell, from a cunning distance, the story of her own life – as a tastemaker who discovered Picasso and Matisse; the host of a starry salon who taught Hemingway and Fitzgerald how to write; and above all as a writer of genius, cruelly neglected by her contemporaries but destined for future recognition, once tastes had caught up. The real Toklas shunned the limelight as determinedly as Stein craved it. Since arriving in Paris from California in 1907, she had devoted herself to Stein – typing up her handwritten texts, screening visitors to the apartment, managing the household budgets, even setting up her own publishing house to print Stein’s books when no commercial publisher would touch them. At their regular open houses, she tended to remain silent while Stein confidently held court. After Stein’s death in 1946, friends encouraged Toklas to write her own memoir at last – but Toklas always refused. To position herself as the protagonist in her own life story felt, to her, impossible. But what she could write, Toklas finally conceded, was a cookbook ‘full of memories’, based on her extensive collection of recipes gathered from over forty years in France.

‘If a traditional autobiography narrates the adventures of a singular self, here life is pointedly presented as a collaborative enterprise.’

The cookbook is a fascinating recasting of Gertrude Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. Though the books’ titles – ironically – bear only Toklas’s name, both reveal two lives, two subjects, each impossible to conceive of without the other. Across thirteen themed chapters (‘Dishes for Artists’, ‘Treasures’, ‘“Beautiful Soup”’), Toklas presents snapshots of her life with Stein through the stories of meals they shared – spreads devised at home, signature recipes gathered from friends and food cooked for them on their travels – interspersed with idiosyncratic words of wisdom: ‘What is sauce for the goose may be sauce for the gander but is not necessarily sauce for the chicken, the duck, the turkey or the guinea hen’; ‘To cook as the French do one must respect the quality and flavour of the ingredients. Exaggeration is not admissible.’ Brisk recipes are prefaced by glittering anecdotes: a fish chargrilled outside, on an open fire, while bulls and flamingos roamed; hot chocolate, ladled from copper cauldrons by Red Cross nuns, during a stint driving ambulances around France as volunteers in the First World War; exploring the French countryside and perusing Michelin Guides in pursuit of the ‘gastronomic bulls-eye’ of a really good meal; a seven-month tour of America in 1934, eating steaks, soft-shell crab and ‘ineffable ice creams’ while Stein delivered lectures to packed-out houses.

If a traditional autobiography narrates the adventures of a singular self, here life is pointedly presented as a collaborative enterprise: Toklas reveals herself indirectly through the gradual unfolding of preferences discovered, friends made, senses awakened. The voice that emerges through the cookbook is wry, curious and quietly authoritative, as she moves subtly between firm instructions and sensual memories. Toklas’s recipes tend to come from other people: chefs, friends, her and Stein’s own household employees, old cookbooks. Yet the pages are peppered with intriguing personal recommendations, as though she’s letting the reader into a secret or subtly guiding them towards her own tastes: her love of garlic and basil, her approval of the French ‘national prejudice’ for butter, an occasional clipped declaration that a certain dish is ‘exquisite’. If she was known to the world primarily through Stein’s witty approximation of her voice, the cookbook reintroduces Toklas as herself.

‘The cookbook is, in many ways, a love letter to Stein, a subtle celebration of their queer domestic routines’

The idea of Toklas writing a cookbook had been a long-standing fantasy between her and Stein. A shared love of food was central to their relationship from the start, and the cookbook is, in many ways, a love letter to Stein, a subtle celebration of their queer domestic routines. Toklas describes how she first became indispensable to the household by making American dishes for Stein, who was homesick, in the tiny kitchen at 27 rue de Fleurus: cornbread, apple pie, fricasseed chicken, Thanksgiving turkey. Emboldened by some successes, she grew ‘experimental and adventurous’ and started to cater dinner parties for the artist friends whose paintings adorned Stein’s walls. One memorable dish was a poached bass for Picasso, decorated with mayonnaise and tomato paste, hard-boiled eggs, shaved truffles and a smattering of green herbs (the artist – whose dietary requirements often tested Toklas’s ingenuity – commented that the colours were more suitable to Matisse). As Toklas and Stein’s relationship developed, the pleasures of eating – often linked with sex – began to suffuse Stein’s writing, a coded homage to Toklas’s growing centrality to her life and work. During a period in Spain in 1912, Stein wrote one of her greatest texts, Tender Buttons, a raucous celebration of language, rendering objects in her immediate surroundings strange – almost Cubist – in an attempt to capture their essence without straightforward description. One section, entitled ‘Food’, presents an array of ingredients for aesthetic dissection. ‘Boom in boom in, butter,’ writes Stein; ‘Celery tastes tastes where in curled lashes and little bits and mostly in remains.’ Toklas, meanwhile, was busy researching varieties of gazpacho. Her cookbook presents recipes from Malaga, Seville, Cordoba and Segovia, offered like edible counterparts to Stein’s literary concoction, combining their complementary domestic arts into one shared and loving practice.

‘Toklas is a deliberately elusive narrator: the spectres of antisemitism and homophobia are evoked through deceptively simple anecdotes about devising menus in restricted markets and servants departing, appalled by the household’s “French ways”’

Some elements of Toklas’s cookbook are more disquieting. One chapter, titled ‘Murder in the Kitchen’, pays homage to Stein’s well-documented love of detective novels: in it, Toklas smothers pigeons and stabs carp, the connoisseur suddenly transformed into a bloodthirsty assassin who pauses only for a brief cigarette before stuffing her victim with chestnuts. Elsewhere, Toklas places these ‘sacrifices of the innocents’ in the context of a discussion of food in wartime, a peril which looms over the whole of the cookbook. It was during the occupation of France between 1940 and 1944, she explains, that she became fascinated by reading cookbooks, dreaming of ‘food there was no possibility of realising’ as a way to block out the ‘black cloud’ of persecution around them. It’s the closest Toklas comes to acknowledging her and Stein’s vulnerability as Jewish lesbians in occupied France, their safety contingent on the goodwill of neighbours and, possibly, on Stein’s long-standing friendship with a high-ranking Vichy official (whose protection – if offered – would nonetheless not have sufficed once the whole country was under Nazi control). Toklas is a deliberately elusive narrator: the spectres of antisemitism and homophobia are evoked through deceptively simple anecdotes about devising menus in restricted markets and servants departing, appalled by the household’s ‘French ways’.

Though Toklas selects her produce with an exacting eye and has an encyclopaedic knowledge of techniques, seasonings and flavours, relatively few of the meals in the book were cooked by her own hand. One chapter is devoted to recipes from a succession of domestic employees hired (with varying levels of success) at the rue de Fleurus, who carried out the bulk of labour in the kitchen. Stein and Toklas find their servants by turns intriguing and infuriating: the most rounded character in the book is Trac, the would-be restaurateur from ‘French Indo-China’ whom Toklas taught to make desserts. She portrays their mutual delight in one another as a simple fact; Monique Truong’s brilliant novel The Book of Salt, narrated by a Vietnamese cook working at the rue de Fleurus, offers a deeper analysis of the impact of colonialism for immigrant workers in mid-century Paris, and casts a sardonic eye over Stein and Toklas’s racialised assumptions.

The household was entirely organised around Stein’s art. Toklas moved daily between her position as manager to the servants who prepared most of the meals (she retained control over the menus, and the selection of produce at the market) and her roles as dutiful secretary, cheerleader and lover to the genius at work. All these roles tended to the invisible, ephemeral: Toklas always insisted her achievement lay in creating the conditions under which Stein could produce the writing both women fervently believed would change the course of literary history. Yet all Stein’s writing – just like Toklas’s cookbook – is testament to their domestic collaboration, a complex, intimate bustle built on an absolute and shared commitment to each other, to the life they made together and to the significance of that work. Toklas devoted her life to feeding and nourishing her partner – both figuratively, by encouraging Stein at her lowest ebbs, and literally, through her meals. Food – when she did cook – was a realm in which Toklas could both serve and create, a domestic art which allowed her to retain the subordinate position she seems to have preferred, yet which also enabled her to forge her own creative path. Toklas continually reminds her readers that the cookbook should not be considered a work of literature – yet, at the same time, she makes a firm case for cooking’s status as a mode of self-expression on a par with painting or writing. The cookbook is full of shapes and colours – of food designed for and by artists – and presented with an eye to high drama: food, here, is art, is history, is language, replete with hidden meanings and subtle codes.

All of this means that attempting to actually cook from The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book can be a risky endeavour. One ‘strange and exquisite’ recipe, acquired by bribing the cook of a prominent surgeon, calls for a week spent injecting a leg of mutton with a marinade of orange juice and cognac through a surgical syringe, while another for sloe gin requires seven years’ infusion. Some are plain bizarre, like the ‘aspic salad’ made by suspending vegetables in a chilled solution of gelatine and Heinz tomato soup, or the whole cold cauliflower with giant prawns tucked between its florets. In June, at a special dinner at Toklas restaurant to mark the publication of a new biography of Stein I had written, Alex Jackson created a Provencal feast from recipes in the book. His menu began with Toklas’s speciality, ‘mushroom sandwiches’, alongside Oysters Rockefeller (served on a bed of sand, as it was in a New Orleans restaurant where Toklas discovered the dish) and ‘Eggplant a la Provençale’: a plump, fried aubergine slice topped, exactly per Toklas’s instructions, with a dab of tomato sauce, the thinnest slice of lemon, and a single black olive wrapped in an anchovy. Then there was a seabass slathered in green sauce (cress, chervil and tarragon) and surrounded by splodges of pink purée (potato, cream and beetroot), followed by chicken served with mashed potatoes and fresh peas. The grand finale was Mâcon cake, a three-tiered buttercream extravaganza, layers infused with kirsch, mocha and pistachio. The original cake was the house speciality of a small hotel in the southeast of France, which Stein and Toklas happened to pass on their way to visit Picasso on the Côte d’Azur. To eat it now is, for a moment, to be transported to a rural French inn in the 1920s, and to be cast into the company of a visionary couple to whom food was art.

Credits

Francesca Wade is the author of Square Haunting (2020) and Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife (2025).

Ella Bucknall is a writer and illustrator based in SE London who specialises in graphic narratives. Ella is currently working on a graphic biography of Virginia Woolf and studying for a PhD in Creative Writing at King’s College London. Ella’s clients include the FT, BBC, and TLS, amongst other publications.

The Vittles masthead can be viewed here.

She is one of the most intriguing people - I wrote much less extensively about her (https://lizhaughton.substack.com/p/alice-b-toklas) and feel she and Gertrude were a beacon and an inspiration in the world then, and still now, living such rich lives. Thank you for this fascinating piece.

" the ‘aspic salad’ made by suspending vegetables in a chilled solution of gelatine and Heinz tomato soup"

Eleanor Roosevelt tried, unsuccessfully, to get FDR to eat this Jello-like pastiche.