The Curious Case of the Beano Cafes

How a network of Turkish-owned cafes became a Kent institution, by Rosella Dello Ioio

Good morning and welcome back to Vittles! We have an unusual story for you as our first newsletter of the year - a very fun investigation by Rosella Dello Ioio into the proliferation of cafes with the word ‘Beano’ in their name across Kent.

Our second magazine, Bad Food, is available on our website and at our stockists, along with prints from our favourite illustrators and photographers. We are planning to hold some in-person events related to the magazine over the next few months, including some where you may be able to get the last few copies of the now sold-out Issue 1. In the meantime, we’ll be releasing a few special features from the mag soon, along with online only content from the Bad Food Extended Universe. Keep your eyes peeled!

The first time I noticed a Beano cafe was in Westgate-on-Sea, a small town near Margate on the Kentish coast. It seemed unremarkable: an old-school cafe offering fry-ups alongside beige banquets, under the signage ‘The Best Beano Cafe & Restaurant’. But as I made my way down the high street, I soon passed the more modestly named ‘Beano Cafe’ and ‘Beano Kebab’ within a few doors of each other. All this in a town of under 8,000 people, with one pharmacy and no proper supermarket.

For those who didn’t grow up in the UK, The Beano is a comic that originated in Scotland. During the 1990s, its characters Dennis the Menace and Gnasher were as ubiquitous as Ronald McDonald. Back then, The Beano was circulating millions of copies per month. They were the halcyon days of magazines, when Smash Hits and Girl Talk filled the shelves. But that was all a long time ago, and these days you rarely see a copy of The Beano outside of a charity shop. Now it conjures hazy images of old-fashioned British boyishness, mischief and simpler times.

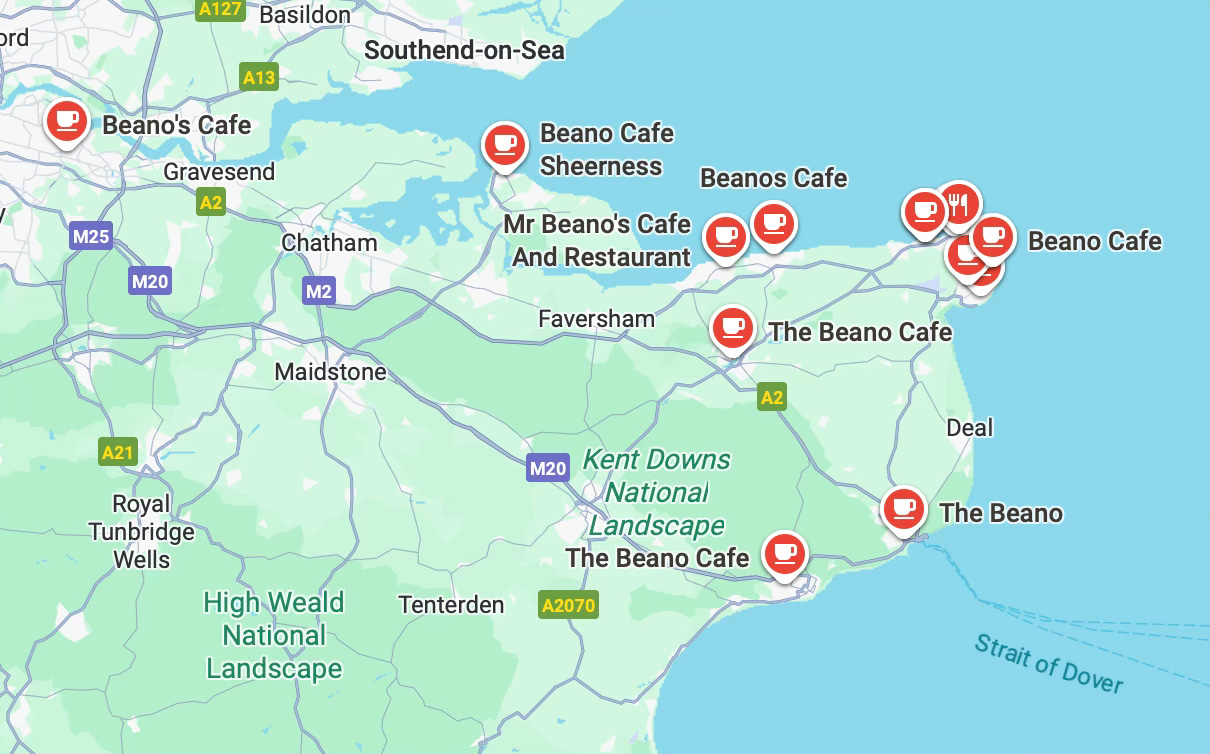

As the weeks went on, I couldn’t help but notice versions of the Beano cafe everywhere I went – from Ramsgate to Canterbury, Sheerness, Broadstairs, Folkestone and stretching as far as the London borderlands in Bexleyheath. Mr Beano Coffee Shop. The Beano. Beano’s Cafe. Beano Family Cafe. I counted fourteen variations in total, all located in Kent (or places which are at least spiritually Kent). Then there were the signs. Some with painted bold red and yellow highlights that echo the nineties comic, others with unrelated 3D lettering and chrome frontage.

My curiosity was piqued. What did a string of cafes have in common with a comic about a spiky-haired menace with roots 500 miles away in Dundee? Was it related at all? Or could it have something to do with the ‘Beano’ coach trips, named after the Scottish slang word for a celebration, which ferried day-trippers from London to the Kent coast in the 1950s and 60s (a concept immortalised in a 1989 episode of Only Fools and Horses, where Del Boy and Rodney go on a Beano to Margate)? Who was behind them? Was it a coincidence, or some kind of franchise? A Kent Live article from 2023 also highlighted the phenomenon and attempted to find the answer, but gave up somewhere between the bacon sandwich and builder’s tea. I decided to get to the bottom of it.

My investigation began at The Best Beano Cafe and Restaurant in Westgate-on-Sea, the first branch I had noticed. It’s one of the larger Beano outposts, with brown and butter yellow signage, a pink feature wall, a diner-style counter and an old black-and-white picture of Westgate-on-Sea, juxtaposed with an Uber Eats sign. It was here I met the Turkish-born owner Gencay Yilmaz and his daughters Dilber and Gizem, who were happy to chat.

We sat down in a red corner booth and they gave me the first insight into the history of Beano. The sisters told me that Gencay moved to Kent from Aksaray, a province in central Turkey, in 1998. The nineties were a time of deep economic and political trouble for Turkey, with high unemployment and soaring inflation. Men like Gencay arrived in the UK, Germany and Italy in search of better opportunities, at a time when immigration routes and work visas were easier. You could perfect a Full English and send some money home. It took five years for Dilber and her mother to join Gencay in Westgate-on-Sea. Gizem was born a year later.

However, Kent’s first Beano establishment wasn’t Best Beano, but the Beano Cafe a few doors down – a modest caff on Station Road, where Gencay first found work. There he learned the rituals of the trade: crispy bacon, runny yolks and strong tea. A few years later, when it was time for him to move on, he decided to start his own cafe, just down the street. He called it The Best Beano Cafe & Restaurant. ‘The cafe name never got trademarked, so anyone can open a Beano,’ Gizem told me. ‘We’re all from the same part of Turkey, in Aksaray. We know each other, but there’s no official business connection, and we’re not a franchise.’

‘Is it a competition?’ I asked Dilber, sensing some intra-Beano rivalry.

She smiled. ‘I suppose you could say that. My uncle in Margate likes a bit of competition. He called his place “The Best Beano Cafe”, too.’

Each new revelation seemed to reveal another, older incarnation of Beano Cafe, like a set of Beano Russian nesting dolls. With two new cafes to investigate, I took the one-minute walk from Best Beano to Beano Cafe, with its laminated Dennis the Menace menu, hoping to learn more from owner Zia Koksal. But he wasn’t keen to be interviewed. ‘My father came to the UK and started a cafe. End of story,’ he told me before returning to work.

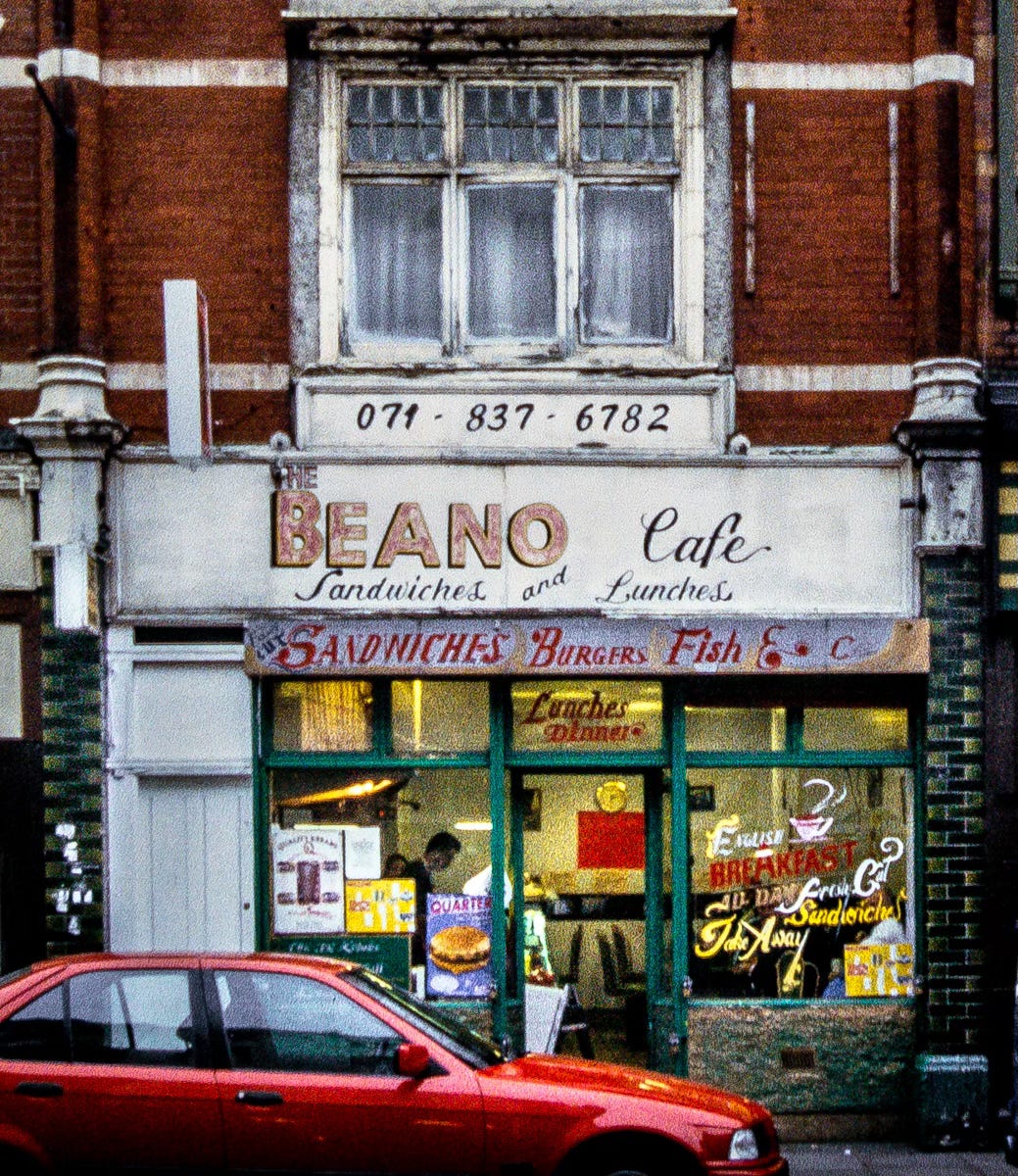

On a second visit, Zia told me that if I wanted to know the full story I should go to Broadstairs to speak to his brother, Zafer. So I headed to Broadstairs, to (yep, you’ve guessed it) another Beano Cafe. It was here I met Zafer Koksal, who told me about the true origins of the Beano Cafe lineage. Beano didn’t start in Kent, but in London. ‘The first Beano Cafe was on Caledonian Road in King’s Cross,’ Zafer told me. ‘My father Mustafa opened it around 1991.’

Formerly a red-light district, Caledonian Road was an attractive spot to start a business in the early 1990s owing to its affordable rent, working-class community and transport links. The dilapidated coal yard (now Coal Drops Yard) had given way to an industrial area full of workers who needed substantial, no-nonsense meals on a budget. This was in the days before chains, when cafe culture was still the land of independents. At the time, Turkish fare had yet to hit the mainstream, and workers wanted bacon and eggs, not döner kebabs. The bar to entry was low, demand was high, and Mustafa found himself in the right place at the right time.

After a few years, Mustafa sold the London location to new owners, setting his sights on life by the coast. He moved to Kent at the turn of the millennium, where he opened the area’s first Beano Cafe in Westgate-on-Sea with his brother. From here, the Beano cafe expanded, with family and friends opening similar ventures. ‘The Beano in Margate, by the clock tower, is my brother-in-law,’ Zafer told me. ‘The Beano Cafe in Westgate [the original Kent Beano] is run by my brother Zia, and the one in Canterbury is my cousin. Business-wise, we’re all independent.’ Still, there are a couple of outliers with no connection whatsoever. ‘Some have sold the businesses and the new owners have kept the same names, so we don’t know all of them,’ Zafer explained. One such place is Happy Cafe & Family Restaurant in Cliftonville, which sports the signature black, red and yellow signage but has no official link to the others.

But why the name Beano, I ask? Zafer shrugs, ‘My father just really loved the comic.’

I was reluctant to accept that the answer could be this simple. I revisited my theory about the Beano coach trips, but on closer inspection, I found that they tended to depart from East London, not Caledonian Road. Besides, by the time Mustafa opened his cafe in 1991, Beano coach trips were already dying out.

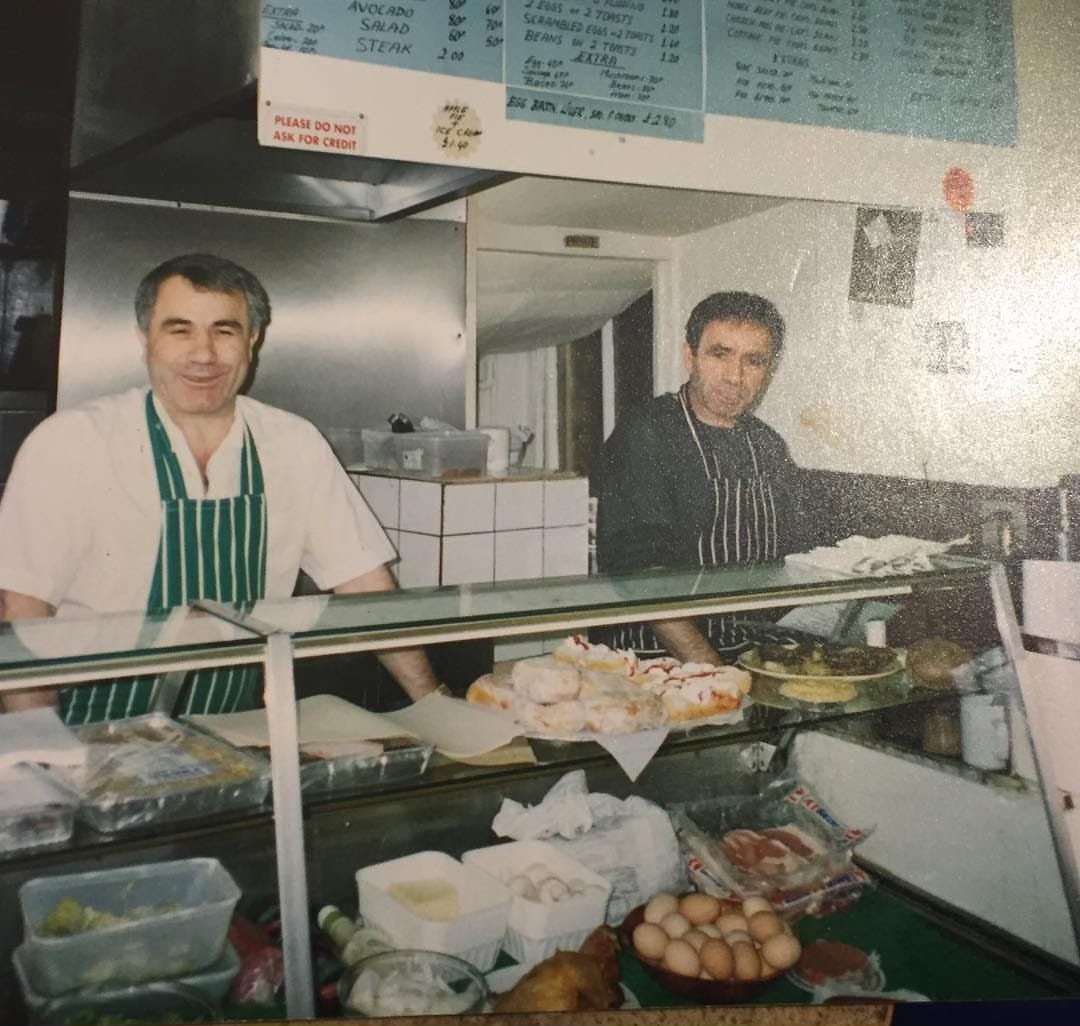

Unfortunately, Mustafa has passed away, so I couldn’t ask him about his intentions for Beano directly. His picture is now etched onto the signage of Beano Cafe Westgate and features on some of the menus and staff uniforms – a reminder of his legacy. Other cafe owners I spoke to kept coming back to the comic as the main motivation for the name and signage. Sometimes, it seems, the simplest explanation is the right one.

Despite the lack of uniformity across the fourteen cafes, two commonalities I found in all the Beanos I visited were, firstly, a deep connection to the community, and also near-identical menus of hot and filling food, the majority of which would leave you with change from a tenner. The clientele are mostly locals, with some tourists in the summer. ‘We’ve had the same customers for over twenty-five years,’ Dilber tells me. ‘First we knew [the] mums and dads, then their kids, now their grandkids.’

I returned to Best Beano Cafe Westgate during a heatwave in the school holidays, and the place was packed with young and old, families, friends and tourists. I passed a group of stylish Gen-Zers hunting for a fry-up and was surprised to overhear one proclaiming, ‘We have to see if Beano has room before trying anywhere else.’

Beano caffs also seem to exist apart from other greasy spoons in the area, which have put a lot of focus into marketing themselves as sort-of museum pieces. Some regularly post reels advertising their latest breakfast innovation. The Dalby Cafe in Cliftonville, for example, has a mega breakfast challenge that has drawn the attention of influencers (infamously, Pete Doherty once took part in it). But the Beano cafes I visited seem to exist in a cultural vacuum, mostly without an active social media presence and unconcerned about appealing to FoodTokkers.

Margate in particular swells with the weight of small-plate restaurants and wine bars, but not everyone has the means or inclination to pay £13 for a plate of anchovies swimming in olive oil. Many want the familiarity of what they grew up with, the straightforwardness of a beef roast dinner with all the trimmings for £8.50, cooked by a person they know by sight, and who has memorised their order.

‘The people around here know us as Beano,’ Gencay tells me. ‘They see me at the cash and carry or out and about in the street, and they shout, “Hey Beano.”’

As an ageing population with a taste for British comfort food continues to decline, the Beano cafes have an uncertain future. Beyond the food, even the name of these establishments feels like an anachronism. The Beano magazine, which once circulated several million copies a year, now distributes around 40,000 per issue. More significantly, there’s the question of succession. These are family-run establishments. Who will succeed the owners?

‘The next generation don’t want to be running a cafe,’ Dilber says. ‘My dad came over in the 2000s and had to get a car, get a house, make a living. We have choices. We were born here.’ Gizem only works at the Beano during the summer holidays when she is on a break from university. Similarly, in Broadstairs, Zafer’s sons only help out at the weekends – one is training to be an electrician and the other is thinking about becoming a plumber. These cafes represent a moment in time, a bridge between old and new Britain, that may not survive another generation.

In Reform-controlled Kent, as in the rest of the country, there is currently a toxic narrative being peddled by the far-right, who want you to think that immigrants are ‘taking over British culture’. But here are Turkish families serving their local communities, maintaining traditional cafe culture for a predominantly English clientele. They’re keeping a slice of British history alive that might otherwise have vanished and become a betting shop.

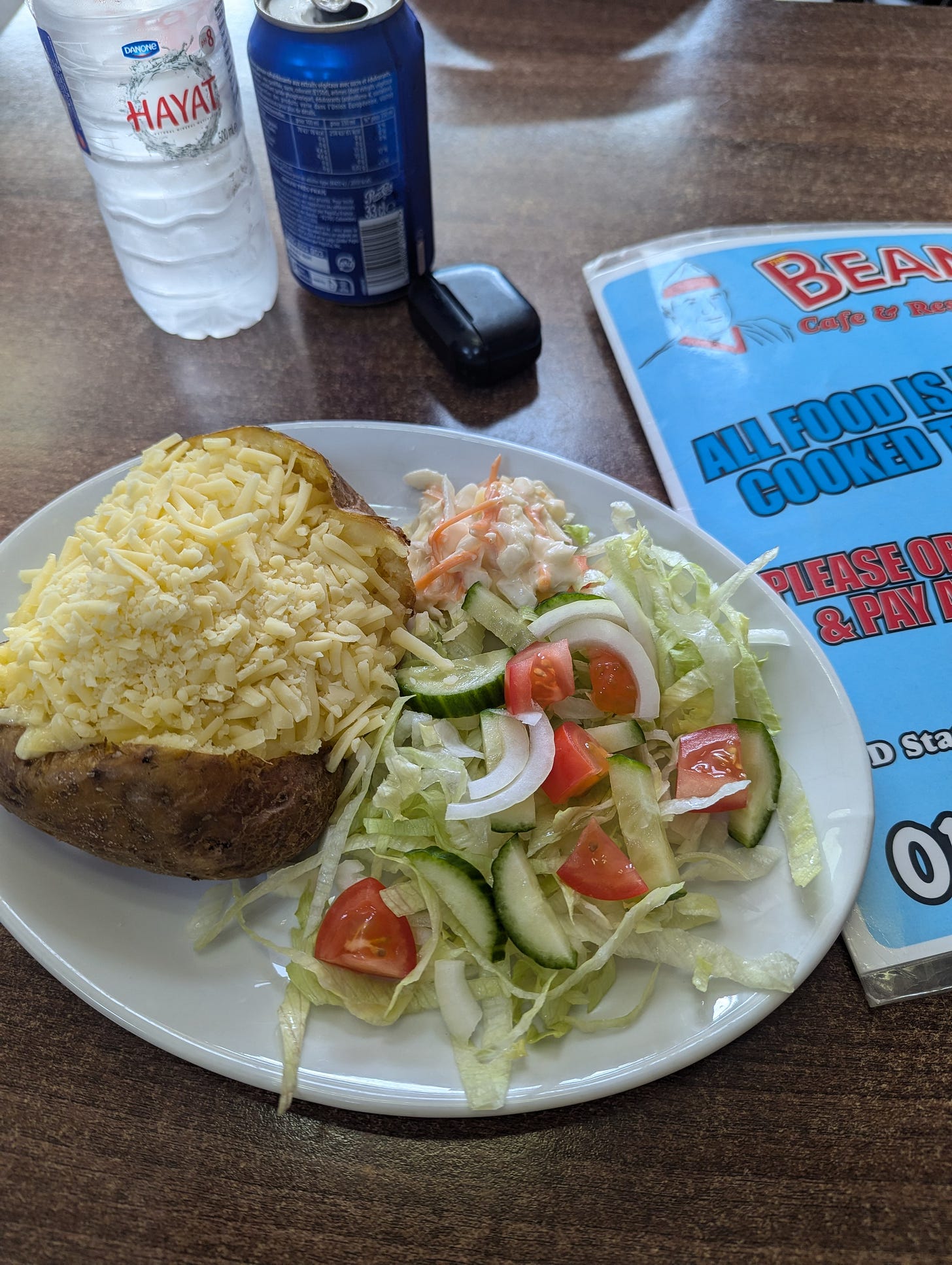

In the end, the name Beano doesn’t really matter. These cafes could have been called anything. What lingers in the mind is their enduring ability to satisfy appetites, not aesthetics. Back at the original Beano Westgate branch, I order a jacket potato for £5.50 – less than a pint at most pubs. It arrives under a heap of butter and grated cheese, which is slowly melting from the heat of the potato. Perfectly crisp on the outside, fluffy on the inside. Shredded iceberg, onion and half-moon tomatoes take up half of the plate, with a dollop of coleslaw for good measure. It takes me back to visiting cafes with my mum in Wales as a child and polishing off jacket potatoes in the same fashion (funnily enough, my order at Ocky White’s cafe in my hometown of Haverfordwest was also called ‘beano’). I look around at the tables filled with chatter from three generations of families, hear the familiar clink of cups and saucers and the hiss of the coffee machine. I lift my knife and fork, and tuck in.

Credits

Rosella Dello Ioio is a Welsh writer based in Kent. She’s interested in food culture and its eccentricities, and is currently working on her first novel.

The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

A “Beano” is an old slang term for a feast - or a treat - as in “let’s go out for a jolly good beano!” so the comic was called “the Beano” implying “a feast of a read” -

My father moved from Pakistan in the late 70s and opened one of the first kebab vans in Oxfordshire in the early 80s. It was called Desperate Dan, the kebab van, named after a comic character from The Dandy. Coincidentally, also a Scottish comic magazine around the same era as the Beano.

People used to see my dad around the town and called him Dan. His name is Abdul. 🤣

I'm seeing him this weekend. Thank you for prompting me to ask him why it was ever called that. I never asked.