The Paradox of the Restaurant Cookbook

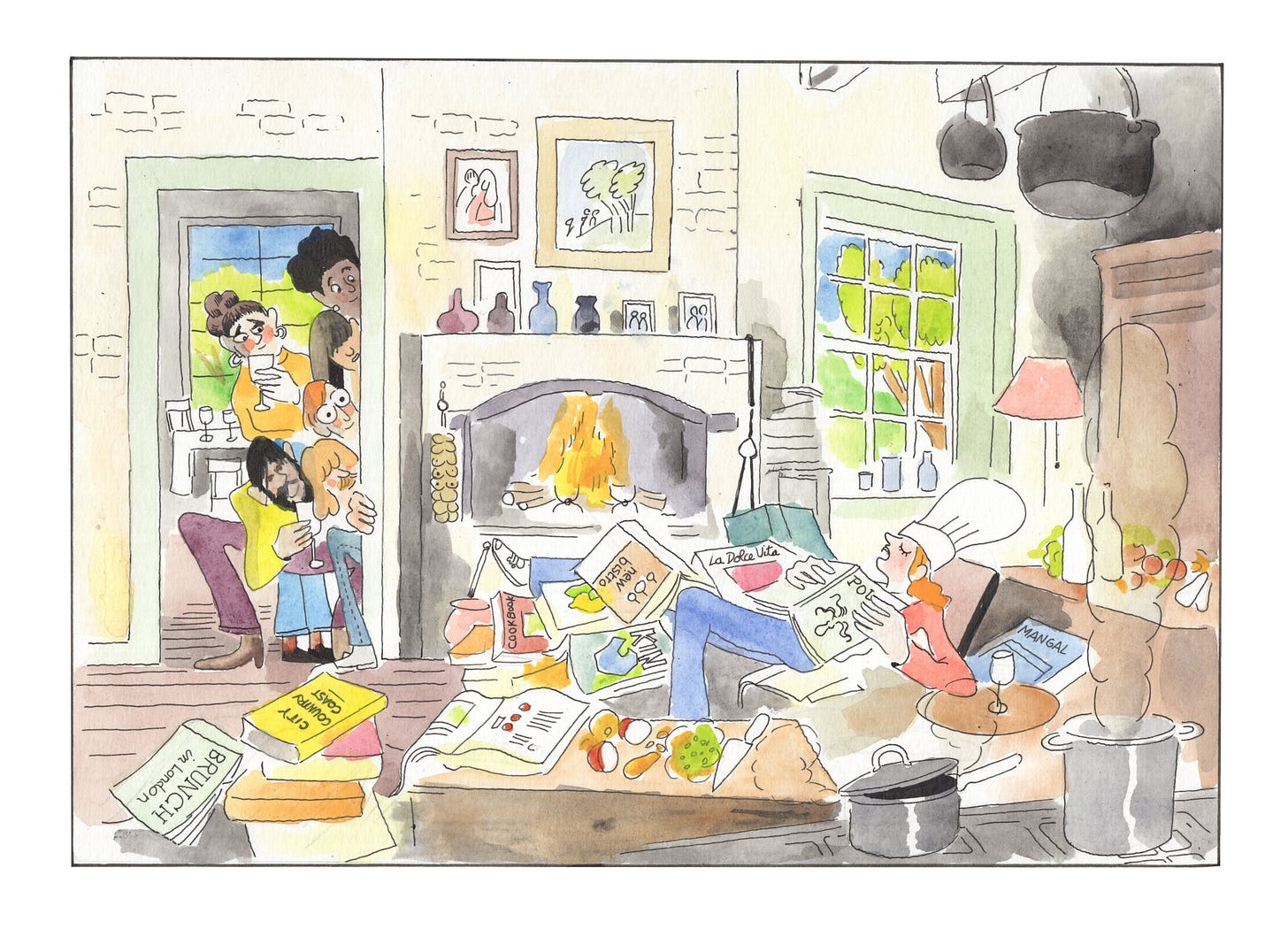

Siobhan Phillips on the contradictions of restaurant cookbooks. Illustration by Antoine Cossé.

Good morning, and welcome to Vittles! Today, Siobhan Phillips writes about the paradoxical genre of the restaurant cookbook – from The French Laundry Cookbook and The River Cafe Cookbook, to the Mangal II and Café Cecilia Cookbook – and weighs up their contradictions and pleasures.

Issue 1 of our magazine is temporarily out of stock while pre-orders are being sent this week. However, we are still selling prints from the issue by illustrator Sing Yun Lee and photographer Michaël Protin, which you can find here.

Consideration of the restaurant cookbook might begin with a concession: these texts are paradoxical. A restaurant justifies its existence, at least partly, by not being its patrons’ home. The restaurant cookbook, then, seems to impose on its readers an assignment they can’t complete: to replicate an experience that won’t ever emerge from a list of ingredients and instructions. Recently, a friend gave me a fat pile of these impossible volumes, ‘purchased after great meals’, she texted. She was culling shelves, cutting losses, and letting go of fantasies. I remained a (somewhat self-aware?) fantasist, by contrast, happy to try my hand, as I delightedly received books of dishes from places to which I’ve never even been. They’d slip easily into a shelf of titles from River Cafe, Dishoom, French Laundry, Café Cecilia, Zuni Café, St. JOHN, Chez Panisse – and more I’m interested in, more I’d love to have, on and on, fill in your own dream.

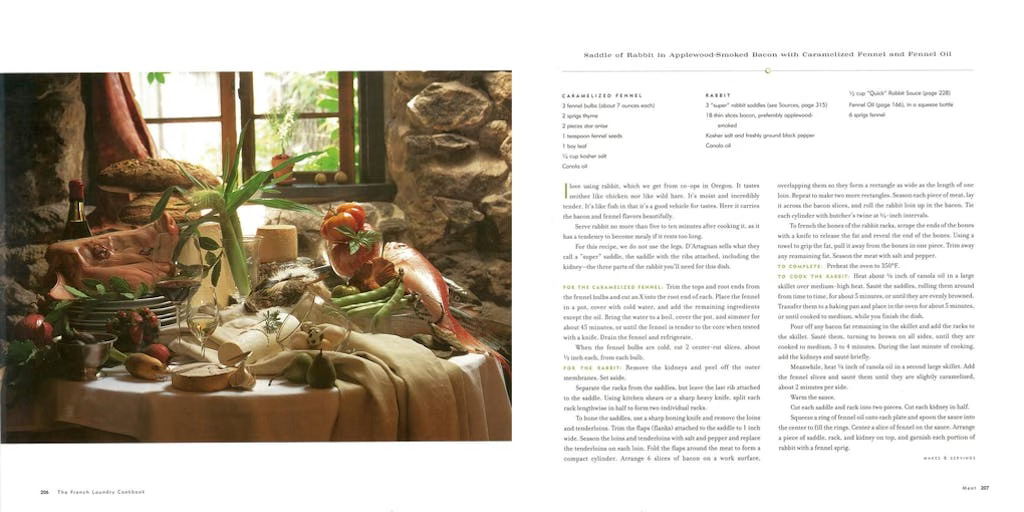

But if restaurant cookbooks can’t erase their defining difference – between a hospitality business and a domestic residence, between a chef and an amateur cook – they find their style in how they manage the gap. Two poles emerge. In one, the restaurant cookbook that refuses to concede a single rung of fine-dining elevation. These texts scrupulously detail what it would take for mere mortals to recreate part of their divinity. The paradigm may be The French Laundry Cookbook, published in 1999, which walks through well-known dishes from Thomas Keller’s Napa Valley restaurant. The book’s sales figures suggest that a perhaps surprising number of home cooks were ready to slice sushi-grade tuna into a carpaccio or turn fresh black truffles into ‘chips’ – or maybe just to read about doing so? Volumes like Keller’s, with their beautifully pristine photos, may be more akin to the well-lit hour of a television cooking competition than the smudged, broken-spine pages of other cookery instructions. They allow the reader to assume collegiality with what is likely to be unreachable skill.

The other extreme of the restaurant cookbook genre makes its common ground from more apparently common stuff. It assures readers that culinary professionalism was never the goal or the source of good tastes, even (especially) for culinary professionals. Instead, these books promise, chefs want to go home, to their family kitchen, which is where they began. It is no accident that the restaurant chefs who put together books of this type tend to be women, people of colour, or both; nearly a decade ago now, in his essential study The Ethnic Restaurateur, Krishnendu Ray pointed out how cooks of non-European descent are confined to a narrative of familial authenticity even if they run successful food establishments and boast culinary degrees. He contrasts The French Laundry Cookbook with another 1990s volume, Suvir Saran’s Indian Home Cooking – it was co-written, like Keller’s, by a Michelin-starred chef, but you wouldn’t know that from a quick skim.

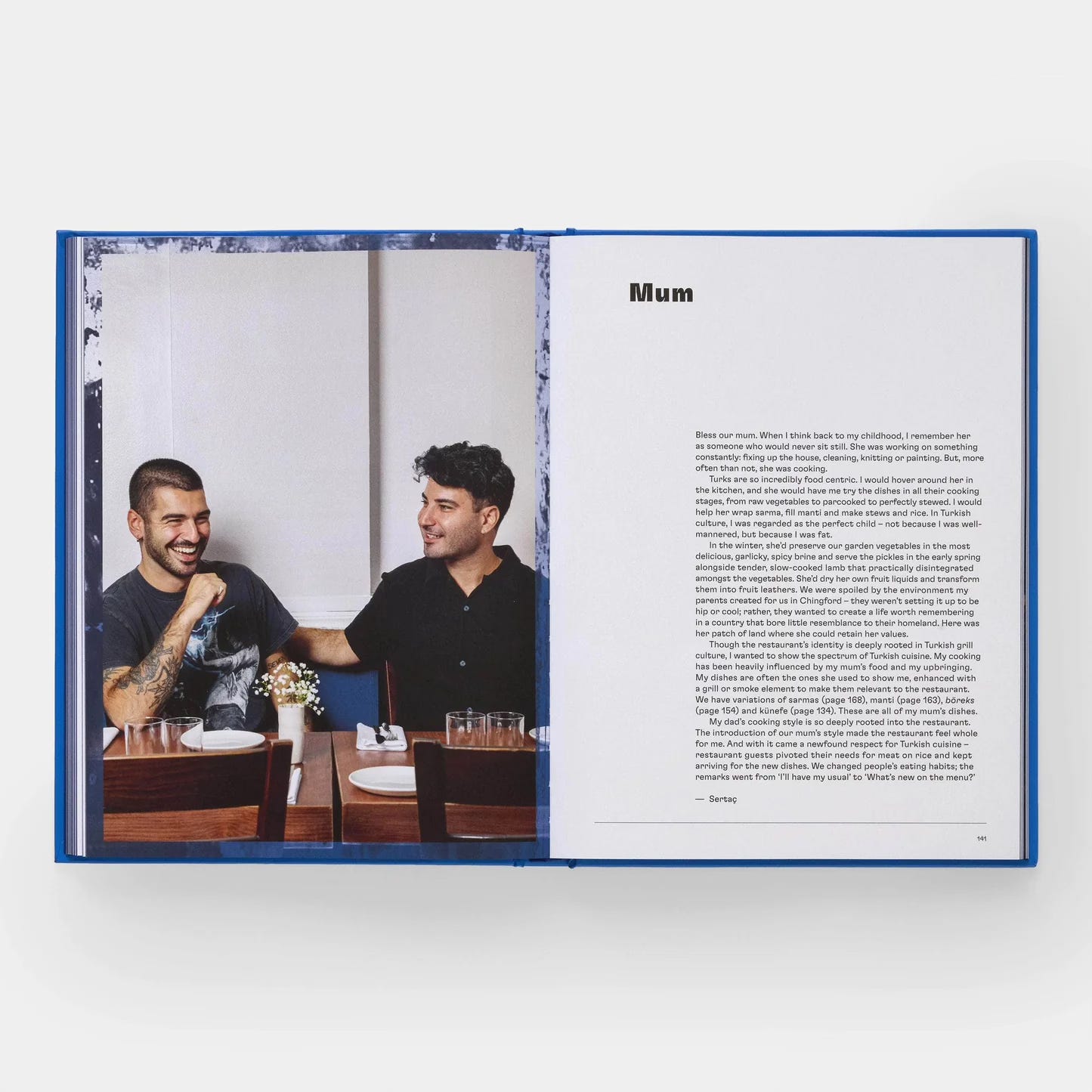

Tastes and tropes may have changed since Ray’s argument – a bit, not enough. The two options I’ve outlined here no longer seem so far apart. (On culinary shows now, aspiring chefs are often ready with perfect French-indebted technique and a tale of their own inspiring origins.) Mangal II: Stories and Recipes, one of last year’s most interesting examples, dips into narratives of professional perfectionism as well as family lineage – we hear about Sertaç Dirik’s punishing apprenticeship in Copenhagen, and we also hear his homage to the cooking he learned from ‘Mum’. But in restaurant cookbooks, the restaurant-chef-as-repository-of-special-heritage may be no less of an imagined ideal than the restaurant-chef-as-repository-of-rarefied-skill. Readers are again invited to relate as equals with an extraordinary cook. And if one kind of text flatters us with the thought that, of course, we need just a little help to awaken our singular genius, the other says that, naturally, we need just a nudge to recognise our dynamic tradition.

I’m not against either flight of fancy. Both have legitimate use and bring real joy. Yet even together, they don’t quite exhaust – or pinpoint – my own relish for restaurant cookbooks. As I page through the ones I really want to spend time with, as well as cook from, I realise I’m looking for more than proximity to great cooks, or even access to great food. I’m also seeking the satisfaction of process, the feeling – as I cook for myself or my family in my resolutely ordinary home kitchen – of being part of the professional, well-run workings of a restaurant team.

‘In restaurant cookbooks, the restaurant-chef-as-repository-of-special-heritage may be no less of an imagined ideal than the restaurant-chef-as-repository-of-rarefied-skill’

Where to find that paradigm? In The River Cafe Cookbook, published in 1995, the Michelin-starred chefs Ruth Rogers and Rose Gray mention family traditions and professional strictures, yes, but emphasise above all their philosophy of ‘a small open kitchen, a menu that would change for every meal, and the unconventional idea that the waiters and kitchen porters would be involved in the preparation of the food’. And the book’s most compelling images show people at the restaurant preparing stuff to eat, in everyday, serious, this-is-our-job sorts of ways: passing behind each other, holding a knife or a loaf, standing attentive over a cutting board or grill, climbing precariously onto a piece of kitchen equipment to maybe look at some ducts, moving rags around the floor with their feet to clean up. It’s in this spirit that readers are encouraged to approach the book – not as a client or guest partaking of the results, and not as a chef or elder presiding over the results, but as one of a group of competent workers executing dishes.

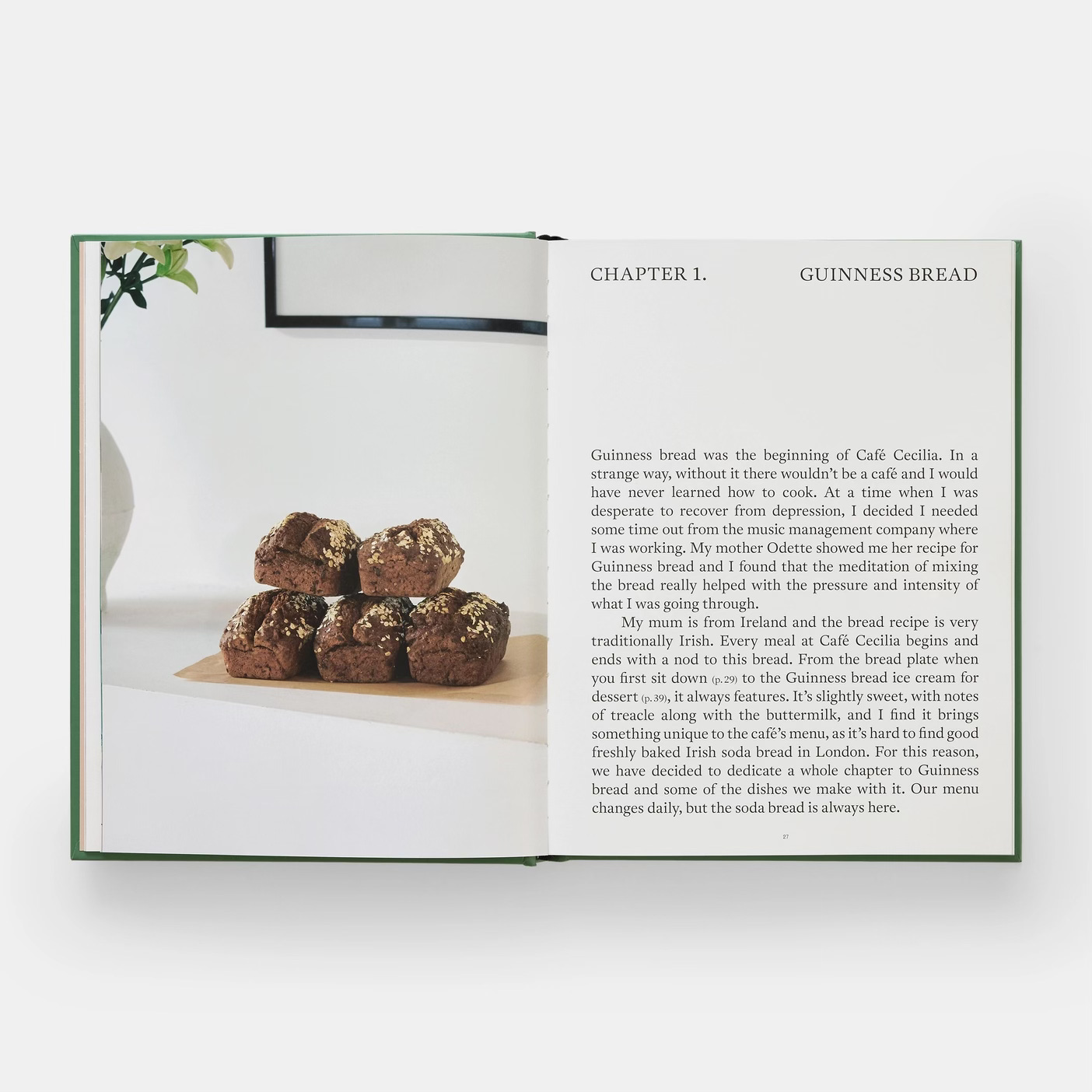

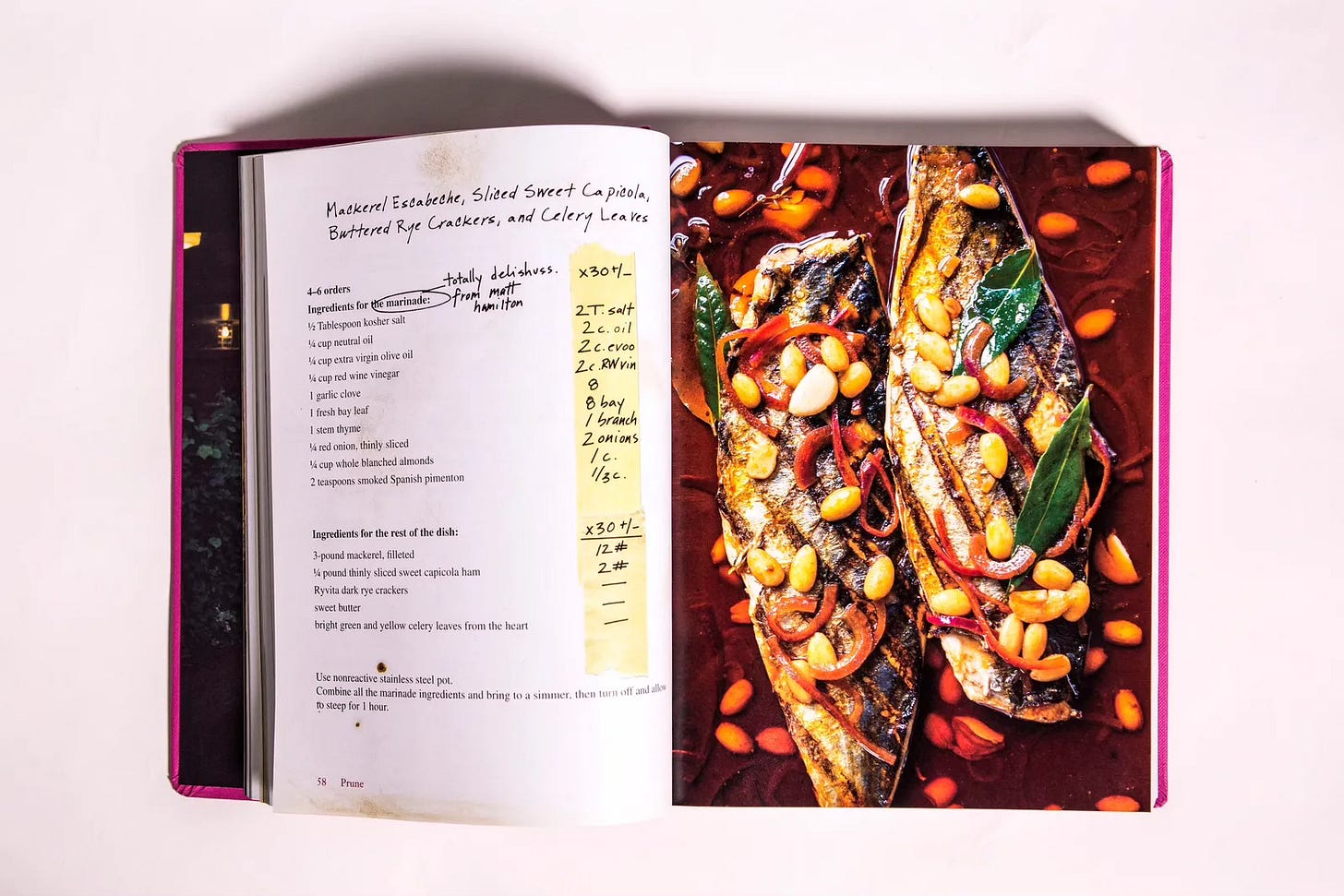

The emphasis on communal competence, or effort, makes The River Cafe Cookbook a particularly potent example of what I like best among restaurant cookbooks right now. In last year’s Café Cecilia Cookbook, for example, Max Rocha explains his hope ‘that the café have a warm environment and that the team be supportive of one another.’ A final section of photos showcasing restaurant employees and suppliers declares that, ‘When the team are strong and feeling positive, it really shows in the food on the plate.’ Rocha learned this approach, he writes, from ‘working at legendary London restaurant The River Café.’ Rocha takes the name of his place from his grandmother, and deploys skills he developed at some of the best restaurants in England, but Café Cecilia’s ethos of camaraderie depends on something other than family roots, something different from chef-y renown. I warmed to a similar teamwork in recent or recent-ish cookbooks from Prune, Superiority Burger, The Four Horsemen, St. JOHN, and others, books that gesture to the reader – come eat this food, yes, come admire the genius behind this food, sure – but also, above all, come spend time among all of the people charged with its production. As I mixed Café Cecilia’s famous Guinness bread, for example, I could feel myself part of the gentle first-person plural that told me, invitingly, how important the daily bread-making was to all of us – even as I slid my own solo loaf into a decidedly non-professional oven.

Does an air of process and invitation make it less impossible for home cooks to create restaurant dishes? Maybe a little. Does it mitigate the unromantic reality of a restaurant cookbook cashing in on the allure of a place or person? Hardly at all. Before the air escapes from this particular meringue of an ideal, however, it may be worth pausing on its strangeness – and significance. The restaurant was established to prevent a blurring of preparation and consumption, eating and cooking. Of course that judgement depends on what one means by restaurant – I’m talking about the contemporary label, begun in 1760s France. Rebecca L Spang, in her important book The Invention of the Restaurant (which I’m indebted to), charts how restaurants distinguished themselves from other options – like the table d’hôte, or traiteur – by promising that one could choose a meal from listed options, according to one’s taste, and eat it undisturbed, alone. The point was hardly just the provision of extra-domestic food, since cities have always offered as much; the allure was rather a privacy-in-public, an individualism in public. That adds some nuance to the story often told (taken from Jürgen Habermas, basically) about food establishments helping to build a busily conversational ‘public sphere’ in Enlightenment Europe. In cafes or coffeehouses people ‘read newspapers, and thought about the world around them,’ as Spang writes, but in restaurants, ‘customers read the menu, and thought about their own bodies’. Restaurants predict a gastronomy that is apolitical and egoistic, directing people’s attention inward: one’s own sensations, not other people’s needs and thoughts.

And not other people’s work and wages, either. The restaurant promoted a vision of citizen as consumer, a vision that has long accompanied and shadowed the modern division of public and private. The typical diner in this scheme can ignore the gender-bound work of the domestic kitchen as much as he (and the typical diner in this scheme is a he) can overlook the class-bound work of a restaurant station. That much is baked into Western European and North American society at this point. But as more than three centuries of politics and activism demonstrate, we desperately need a different model if we are to avoid the worst of inequality and atomisation that comes with modern capitalist culture. Instead of citizen as consumer, perhaps we might think of citizen as labourer – an ideal that makes plain the activity of the household as much as the activity of commercial establishments. Restaurants obscured just this clarity, as Spang explains, when they established a chasm between making food and enjoying it. They supported the prominence of the chef, in his rarefied no-place of vision and skill, and the uniqueness of the gourmet customer, in his egoistic bubble of taste and righteousness, but erased the existence of staff, who served the vision of one and the appetite of the other.

‘The restaurant promoted a vision of citizen as consumer, a vision that has long accompanied and shadowed the modern division of public and private’

So when restaurant cookbooks spotlight the making of food, they signal a subtle historical or ideological shift. Not all restaurant cookbooks have followed suit, of course (at least not all quite as much), but it’s there in the photos of Balthazar, from that restaurant’s 2003 text, as the images move between dining room and the spaces of preparation; it’s there in the extensive introduction to the cookbook from The Four Horsemen, published last year, which again pays homage to ‘Rose and Ruth’; it’s there in the no-fuss ‘we’ of The Book of St. JOHN, from 2019 (‘our kitchens are open,’ the book declares); it’s there in the narrative of an ‘incredible crew’ at Mangal II creating their sourdough pide recipe; it’s there in the ad hoc instructions to staff, reproduced in a handwritten font, that pepper the Prune cookbook of 2014 (which prints an ‘employee manifest’ in its endpapers). My pleasure in these books feeds on their matter-of-fact rejection of the restaurant as an institution of individualism and prestige. (And while labels don’t mean much anymore, it seems un-accidental that Rocha’s restaurant, like Rogers’s and Gray’s, is styled as a ‘cafe’, that The Four Horsemen at first labelled itself a ‘wine bar’; Mangal II, meanwhile, draws on the communality of the ocakbaşı format.)

These books turn the restaurant away from Habermas’s theory of privacy and publicity and toward Erving Goffman’s theory of social dramaturgy, which describes how people move between various versions of a ‘front region’ and a ‘backstage’ as they go about daily life. We all have to perform, continually. But amid the wear of such performance, we all get those treasured ‘backstage’ moments of alliance, commiseration, and teamwork. Restaurant cookbooks in the vein I’m describing give us that ‘bond of reciprocal dependence’ that Goffman identifies in the ‘backstage’ regions. If this is so, moreover, these volumes are not so compromised after all. They’re not attempting to wrangle some second-best version of a restaurant patron’s or restaurant chef’s experience; they’re offering a different experience altogether – one you can enter, imaginatively, through a book more completely than you can through any brick-and-mortar establishment.

‘They’re not attempting to wrangle some second-best version of a restaurant patron’s or restaurant chef’s experience; they’re offering a different experience altogether’

But what about the actual goings-on in such establishments? Restaurant work is not, as plenty of first-hand accounts have testified, a haven of shared effort. More often it’s a hell of top-down hierarchy and harassment – many times, racist and sexist harassment. Sometimes chefs who admit to sustaining horrible working conditions write highly lauded cookbooks. Not those chefs and cookbooks in which I’ve found the Goffman-esque paradigm I’m describing here, but that probably doesn’t matter much. The economic structure remains fairly consistent across the industry, and brutal in its basics: restaurant jobs pay poorly, profit flows to stars and owners, and privilege generally dictates who has a chance of financial control. Max Rocha, for example, comes from a ‘successful family’ – he discusses this frankly in the introduction to his cookbook – and thus ‘had a leg up’ even as he was ‘working as hard as I can’.

So, the communal labour to which I’m pointing, among the pages of some restaurant volumes, might accurately be described as façade – one more story these books are selling. The story of escaping from the selling. But I could also (and this is where I’m trying to land) take it as an aspiration: a reminder of our basic yearning for common activity towards a shared necessity. The ways we currently tend to prepare and eat food – at home or in a restaurant, for ourselves or for others, as a professional or as a home cook – may not feed all our needs and hopes. When I make that Guinness bread from the Café Cecilia Cookbook, or the focaccia from The Four Horsemen, or the pide from Mangal II – or any number of other restaurant dishes out of books – I don’t improve the reality of food labour. But I might be honouring the desire for something better, as the complex restaurant-cookbook alchemy of reader and text sustains an appetite for what cooking and eating may yet mean. Which is not nothing? Also: the Guinness bread and focaccia and pide are delicious.

Credits

Siobhan Phillips is the author of the novel Benefit as well as various nonfiction works. She teaches at Dickinson College.

Antoine Cossé is a French illustrator and cartoonist living in London. He regularly contributes to The New York Times and The New Yorker, and his graphic novels are published internationally.

The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

Not all restaurant cookbooks are the same nor are they intended for the same purpose. Many of the fine dining persuasion are coffee table stacks intended for the restaurant’s (or more likely, the chef’s) ardent fans.

Ownership is a matter of pride for the purchaser and their publication is a status symbol of achievement for the subject. (Cynically, it’s not bad PR). For example, Noma, Centrale and Gordon Ramsay’s totemic sleeved cookbook for this eponymous London three star.

Realistically, owners do not cook the food. Instead they gain a printed insight like pulling back the veil to glimpse behind the scenes.

Then there are the everyday restaurant cookbooks which are more accessible and I’d argue those are more influential on the culture of cooking and the public at large—Ottolenghi and The Silver Palate makes that point.

A really interesting analysis with which I mostly agree. Sourcing restaurant-style Ingredients, rather than method, presents the most obvious dichotomy. Where does the home cook find quantities of fresh langoustines or even proper spinach?

But, as a restaurateur, I was dismayed to read that old trope about staff being paid poorly while owners accrue vast wealth. It is simply untrue. Even in the countryside, a middle-ranking person can earn £50k-plus while, after five years of trading, April was the first month we took anything — a princely £3k.