The Story of Japanese Food Told Through Four Arts

Pottery, Manga, Literature, Printmaking. Words by Kambole Campbell, Hugo Brown, Jelena Sofronijevic and Jonathan Nunn

Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 6: Food and the Arts.

All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £600 for writers (or 40p per word for smaller contributions) and £300 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations. Vittles subscription costs £5/month or £45/year ─ if you’ve been enjoying the writing then please consider subscribing to keep it running and keep contributors paid. This will also give you access to the past two years of paywalled articles, which you can read on the Vittles back catalogue.

If you wish to receive the Monday newsletter for free weekly, or subscribe for £5 a month, please click below.

The Story of Japanese Food Told Through Four Arts

1. Pottery: How Japanese Food Became Everyone’s, by Jonathan Nunn

When I used to work in tea, one of our favourite things to do when there were no customers in the shop was to watch YouTube videos, mostly of old food adverts from the early 90s, like the Tango advert that led to a real-life spike in slap-based assaults, or the Gino Ginelli advert which was ahead of its time in its rejection of Italian food orthdoxy (sample lyrics: ‘Take home a Gino Ginelli ice-creama piazza Italia’). I can’t remember how many videos deep we were when we came across an account that scoured online videos of people conducting Korean tea ceremony, and denouncing them as inauthentic. Whenever anyone did something that the narrator disapproved of – using an electric kettle, pouring the tea in the wrong order – the Queen song ‘Liar’ would play, while the word ‘FAKE’ flashed up on screen.

Debates over the correct preparation of tea – like debates over the correct preparation of any other food – are so often a proxy war for something else. In this case, the account was run by a right-wing Japanese nationalist who saw the ceremonies as a Korean encroachment on what he considered to be a purely Japanese art. These review videos were playing into a long history of distrust from Japan to both Koreas, one that has been exacerbated in recent years, with Shinzo Abe (Japan’s prime minister from 2012 to 2020) repeatedly making revisionist statements about Japan’s colonial role on the peninsular, and appearing to minimise war crimes. Yet the Japanese right-wing distrust of Korea is not just historic; there is an increasing paranoia about North Korea’s geopolitical aims, as well as a kind of jealousy at the popularity of the Hallyu – the cultural wave of Korean influence, from TV dramas to K-pop, that has done for South Korea today what Nintendo and Studio Ghibli did for Japan in the 90s.

Yet even as these videos impotently raged against the Korean ‘appropriation’ of the tea ceremony, they ignored that there was once another Korean wave, back in the Koryŏ era (918–1392 CE) during which both tea and ceramics, as well as Japan and Korea, were completely entwined in a shared history of exchange and colonisation. Tea, before it became the most consumed beverage in the world, was once an obscure Chinese medicine, and it was only during the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) that consumption of Chinese tea became elevated into something close to an art. Tea expert Timothy d’Offay writes that in this time ‘the cultivation, processing and preparation of green tea became a skilled practise and art with its own set of protocols.’ Before this, tea would have been steamed and compressed into a cake, or drunk as an infusion with adulterations like salt, cloves or fruit peel.

During the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE), green tea in China evolved again, starting to be ground into a very fine powder and whisked into milky-white froth. This pale proto-matcha was one of several factors that influenced the more limpid style of ceramics which emerged from the Song period. Chief among them was the development of celadon, a glossy, pale green-blue glaze conjured through iron oxide, which had the added attraction that it could show off the colour of the white frothy tea. Over in Korea, meanwhile, where loose-leaf tea and its attendant ceramic tradition had spread through the movement of Buddhist monks, the Koryŏ intelligentsia codified more elaborate ways of drinking tea, utilising ever more beautiful celadon bowls with decorative patterns to drink their tea. The ceremony of drinking tea in Korea became multi-sensory, with aroma, taste, colour and texture all in harmony; a celebration of nature and craft, as well as religious and philosophical ideas. The most sought-after potters were the Jungkooks of their day.

As the Koryŏ era faded, neo-Confucianism supplanted Buddhism as the dominant way of thinking. Buddhist temples (and, by extension, Korean tea drinking) went into decline. But the Korean influence on tea culture and ceramics left a lineage in another, unexpected, way. In the late sixteenth century, when Japan invaded Korea, many of the most skilled Korean potters were forcibly removed to go work in Japan, where ‘Korai chawan’ (Korean tea bowls) had become highly prized. It was through these potters that many styles of pottery now considered to be Japanese – for example, mishima and karatsu – were first produced. It has even been suggested that Tanaka Chōjirō, the founder of the Raku line of potters (perhaps the most prestigious pottery lineage in the world) and a close collaborator of Sen no Rikyū, who codified the Japanese tea ceremony, may have been the son of one of these potters. At the same time, that Chinese frothy white tea – through refined shading techniques and processing – started to resemble the emerald-green matcha we know today, and can now be found in lattes and dessert bars across the world. This tea is not just the cornerstone of Japanese tea ceremony, but the entire kaiseki meal that precedes it, which itself has gone on to influence the aesthetics of every Michelin-starred restaurant in the UK, France, Scandinavia and the US – from the lighter techniques of cooking it advocates, to the plating and the use of glazed and unglazed ceramics to present food. The next time you eat something too austere to enjoy, from a plate that cost more than your monthly rent, you know who to thank.

Japan’s tea ceremony, like its cuisine, is not pure, even if Japanese culture is so often essentialised – both by foreign Nipponophiles who insist that everything about Japan is special and unique as they talk in hushed tones about their favourite shokunin, as well as right-wing Japanese historians who see Japan as an isolated and exceptional island surrounded by inferior cultures (where have you heard this before?). Many cuisines of countries that have been colonised are euphemistically described as ‘confluences’ – French and Vietnamese, Portuguese and Goan – while the cuisines of the coloniser are considered to be pure. Yet so much of what we believe to be uniquely Japanese has its origins somewhere else, whether it’s the tea ceremony which was refined in Korea, ramen that came from China, or even its recent rural nostalgia for traditional foods which, as Rachel Laudan points out in her excellent book Cuisine and Empire, was part of a backlash against foreign imports like pizza and fast-food burgers.

Today’s newsletter is a compilation of stories about Japanese food told through its art, but it is also a compilation of stories that emphasise the influence of the outside, whether it’s Jelena Sofronijevic on Hokusai’s documentation of Chinese food production techniques, Hugo Brown on American food in post-war Japanese novels, or Kambole Campbell on Ainu food in the manga Golden Kamuy, and Japan’s indigenous population who are treated as peripheral. Each shows that the urge to see any cuisine as pure and untouched is not just strange, but a kind of myth-making – this is true of Japan as it is of the UK, Greece or Italy, and anywhere that food becomes sucked into culture wars. As Alberto Grandi pointed out in a recent Financial Times piece, ‘tradition is nothing but an innovation that was once successful’. I’d add that what we consider to be native to a food culture is nothing but the foreign that has become familiar. The story of Japanese food is maybe the greatest global food story of our time: a cuisine that was once foreign everywhere and is now as familiar as a meal deal. Like Italian food before it, it now belongs to everyone. I’m not saying we need to go as far as doing a Japanese Gino Ginelli, but I look forward to more abominations becoming new traditions.

Today’s intro is expanded from an essay originally commissioned by the Victoria and Albert Museum. To learn more about the Hallyu you can visit the V&A’s new exhibition in London here.

2. Manga: Ainu food and remembrance in Golden Kamuy, by Kambole Campbell

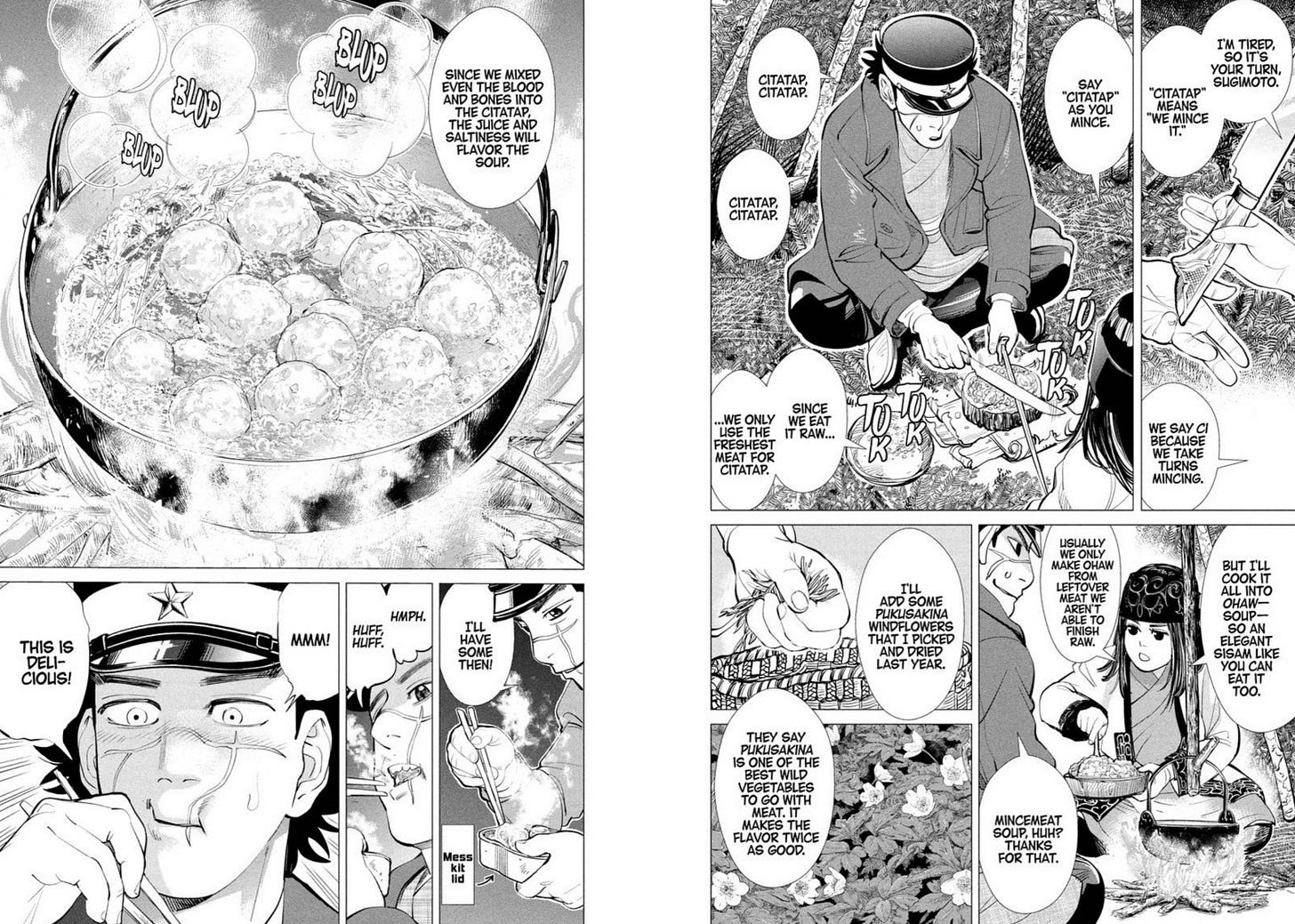

There’s no shortage of work dedicated to the pleasure of food in Japanese visual media. Bowls of ramen are evangelised in the comedy western-eastern romance Tampopo, while peripheral meals in Studio Ghibli anime are lingered over on fan sites as if they were main characters (Isao Takahata’s film Only Yesterday does, in fact, centre a cherished memory of family around a pineapple). But it’s a manga, Golden Kamuy by Satoru Noda, that contains some of the most striking depictions of food of all. Just look! Squirrel mincemeat soup cooked with windflower; orca fried into tempura; fresh animal brains eaten with salt.

This is not, however, Japanese food as it is typically known. Instead, it is a small part of the cuisine specific to the Ainu, a people indigenous to the area surrounding the Sea of Okhotsk (which includes the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido and the Russian-controlled Sakhalin and Kuril islands). By 1907, when Golden Kamuy is set, the annexation of Hokkaido by the Japanese state, and forced integration of the Ainu, were well underway. Over the preceding century, the Ainu population had plummeted as they were systematically disenfranchised through various methods: their land was stolen; hunting and fishing bans were put into place; forced marriages to non-Ainus were imposed; and they were made to take on Japanese names. The effects of these policies are still felt today, with a vast number of Japanese citizens unaware of their Ainu heritage due to lost ancestral knowledge, or having to hide their identities. Over the course of Golden Kamuy, depictions of food unlock a more expansive history and viewpoint of Japanese cuisine that is usually shown in nationalist narratives, highlighting the customs and culture which have been suppressed by imperialism and assimilation.

Golden Kamuy begins with the meeting of Saichi ‘Immortal’ Sugimoto – an impoverished and heavily battle-scarred veteran of the Battle of 203 Hill in the Russo-Japanese War – and Asirpa, an Ainu girl and accomplished hunter. After a bear attack forces them to team up, Asirpa and Sugimoto establish themselves as equal partners, then close friends. The plot follows their intertwined journeys across the land – a search for a hidden fortune of gold stolen from the Ainu that they both have their own reasons for needing. If you think this makes it sound like a Western, then you’re right: fans of the series colloquially refer to it as a ‘yaminabe Western’ (hotpot Western), in homage to Sergio Leone’s ‘spaghetti Westerns’ (which, in turn, are a homage to Akira Kurosawa).

In the first volumes of Golden Kamuy, which were published in 2014 and drawn in black-and-white sequential panels, Noda renders Ainu food as inviting, warm and lush; while the characters’ faces are drawn with efficient and sometimes cartoonish elastic line-work, what they eat is drawn with meticulous and realistic detail. Noda uses the production of each dish as a way of foregrounding Ainu history and zoography: stews, soups and dishes of game and fish are tracked back to their source in Ainu hunting and fishing culture. Animals are caught using rawomap (wooden branch traps sunken in water to catch river fish throughout winter) and eagles by hook hunting – practices that row against the capitalist annihilation of various species via commercial hunting. The series goes on to unpack indigenous cuisine across the surrounding areas, like the Uilta (or Orok) and Nivkh people of Sakhalin (Japan’s Karafuto prefecture at the time), as well as the Ainu who also lived there. Noda dismantles monolithic ideas not just about Japanese food, but even within the Ainu (salmon fishing is key for the Karafuto Ainu, while Nivkh meals include ‘most’, a mix of fish skin, berries and fat, frozen in the outside cold).

Food is shown as a pathway to memory, both personal and historical. Sugimoto remembers the time before the ruinous war through the taste of persimmons, for instance, and through her hunting and cooking practices, which she teaches Sugimoto; Asirpa remembers her father, who taught her what she knows. The detail of these things was so important to Noda that he went as far as to eat fresh deer brain with an Ainu hunter so he knew how it tasted (like bland gummy sweets, apparently). Food is also the primary signifier of culture between Sugimoto and Asirpa. The first of the dishes that Asirpa shares, chitatap, becomes a frequent callback. The dish’s preparation involves each person chopping the meat into mince while repeating the word ‘chitatap’ (meaning ‘we mince it’), which becomes a hugely exciting social ritual to Sugimoto and his other travel companion Shiraishi. Asirpa also adapts her cooking so that, in her words, ‘an elegant sisam like you [Sugimoto]’ can eat it, cooking her chitatap into a stew rather than eating the minced meat raw as is custom. In another instance, Sugimoto adds miso to fish, beginning a long-running joke about Asirpa’s disgust at its appearance, and then reluctant enjoyment of its flavour.

Ainu cuisine is often talked about in the West (as well as in Japan) in terms of what it gave the Japanese: for example, kombu and the resultant umami flavour have their basis in Ainu cooking, according to Remi Ie, Director of Slow Food International Japan, and Hiroaki Kon, an Ainu chef and owner of the Kerapirka restaurant in Sapporo. But there are moments in Golden Kamuy – even if it’s just sharing miso and frying whale into tempura – which represent a kind of wish fulfilment of what could have been: a genuine exchange between cultures, rather than the erasure of one by the other.

Golden Kamuy was so popular within Japan that it helped catalyse a new ‘Ainu boom’ – similar to what happened with manga in the 1950s and 60s, when there was widespread resurgence in Ainu cultural practices and language, as well as organisation. It inspired famous mangaka to focus on Ainu protagonists, like Osamu Tezuka in his work Brave Dan, or Yoshiharu Tsuge with his epic Iomante no Otome. Books that have long been out-of-print, such as Harukor by Ishizaka Kei (which was made to heavy resistance in the 1980s) have since been reissued.

But there are downsides to this new boom, a subject broached in the 2020 film Ainu Mosir, in which the Ainu and their lands are used as a tourist attraction. Noda is conscious of this tension: ‘I’m a wajin [the majority ethnic group in Japan], so I’m always striving to remain neutral within that space’, he once said. Noda sought to represent the essence of how the Ainu lived, rather than only how they were made to suffer and assimilate. In an interview with his editor Ookuma Hakkou and his Ainu-language consultant Nakagawa Hiroshi, Noda talks about when he met the Ainu – they ‘only once told me what to do: “Please do not write about miserable Ainu, [instead] write about strong Ainu for us.” That was all.’

The presence of Ainu cooking in Golden Kamuy is part of this resistance to the erasure of indigenous cultures, a procedure of recollection. A note in the fourth volume of the book says that the Ainu favour oral storytelling over written folktales or history. If we continue to speak of this knowledge, their history continues.

3. Literature: The Bar Food of the Economic Golden Period by Hugo Brown

For Japan, as for many countries, the years following the Second World War were filled with great change. For those of us whose perception of the war is framed through the European theatre, it’s easy to forget that it wasn’t until 1952, seven years after the end of the European conflict, that the American occupation of Japan ended. During the war, Japan had already endured the destruction caused by atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki; economic hardship following the invasion of South East Asia (due to industrial redirection to the war effort); and mass starvation caused by US trade embargoes paired with domestic economic and agricultural practices. After the war, the Japanese army was demobilised, Emperor Hirohito lost all power as the country moved from Imperialism to democracy, and Shinto, the national faith, was separated from the state.

Despite this period being a time of cultural upheaval, the decades following the war – from the late 1950s until 1992 – were those deemed the economic ‘golden period’. During this time, through American occupation and a more open foreign policy, Japan also accelerated its import of a certain kind of Western influence, one that had begun in 1868 with the beginning of the Meji period. After the war, American aid meant that wheat, bread, flour, corn and milk were more prevalent, with a shift in ingredients also leading to new dishes – curries, spaghetti, fried cutlets – and the popularisation of ramen. This gave further rise to yoshoku – Western-style Japanese food which uses Western ingredients in a way that is familiar to Japanese palates, like, for example, Omurice, chicken karaage, chicken fried rice, chicken cheese katsu and curry ramen – which was again rooted in the Meji period. An uptick in purchasing power, and an increase in urban population, meant that many more people in Japan started to eat out. Yoshoku’s emphasis on easy-to-prepare set meals and combos using inexpensive ingredients made it popular in a casual dining-out culture based on a multiplicity of dishes.

It is, in other words, the perfect solo bar food.

It’s possible to argue that this movement in Japanese dining culture allowed for a certain style of literature to emerge in the twentieth century (particularly in the 60s, 70s and 80s) – one which dealt with the themes of love and loss, isolation and union, dissatisfaction, and detachment, often using the medium of food. Writer Kenzaburo Ōe touched on this in 1964 with his novel A Personal Matter, where his isolated narrator Bird drinks to excess and is horrified by food, and the tradition survived all the way up to writers like Hiromi Kawakami, whose novel Strange Weather in Tokyo (2001) is catalysed by a meeting in a bar. It was the explosion of bar culture, changing gender roles and new ingredients and cuisine that were at the heart of this literary trend.

In novels, writers used yoshoku as a contemporary cultural catalyst to propel their isolated Japanese narrators into the world. We see this in Haruki Murakami’s Norwegian Wood, for instance, and in Banana Yoshimoto’s 1988 book Kitchen, which is contemporaneously set. In Kitchen, there is a scene where narrator Mikage realises she is in love, and she uses a yoshoku dish – the katsu don – to declare this, taking it to her lover Yuichi. ‘That’s how I came to find myself standing alone in the street, close to midnight, belly pleasantly full, a hot takeout container of katsudon in my hands, completely bewildered as to how to proceed’, Yoshimoto’s narrator muses.

In the latter half of the twentieth century, the gaze of writers and their often-young narrators moved away from the home towards bars and restaurants. In books like A Personal Matter, Kitchen and Yoshimoto’s Moonlight Shadows, plus Murakami’s 1Q84 and Hear the Wind Sing, characters inhabit food establishments in the city as if they were their homes, drinking excessively in bars whose bartenders often occupying an almost parental space. Bird from A Personal Matter is perhaps the most morally compromised example of this. ‘Bird had hoped at least to achieve a little humour in his vomiting style, but his actual performance was anything but funny’, Oe writes about his narrator, who has once again publicly drunk himself to destruction while avoiding the birth of his disabled child. Murakami, who owned a bar himself, uses these spaces to depict the changing culture of Japan. Things like The Beach Boys, Hawaii Five-0, Cutty Sark whisky, cooking spaghetti and the Beatles appear frequently in his books. His first novel Hear the Wind Sing is set largely in a bar which serves only French fries: ‘The chill of the air conditioning met me when I backed my way as usual through the heavy door of J’s bar, the stale aroma of cigarettes, whiskey, French fries, unwashed armpits and bad plumbing all neatly layered like a Baumkuchen.’

The novels of the economic golden period also depict female protagonists who drive plots in ways previously uncommon and therefore unconventional. Yuko Tsushima’s 1978 novel Territory of Light presents a flawed protagonist: a separated single mother who struggles with depression, drinks too much and is neglectful when looking after her daughter. In Kitchen it is Mikage who seeks out Yuichi, and this tradition continues in Hiromi Kawakami’s Strange Weather in Tokyo, where it is protagonist Tsukiko who approaches and pursues Sensei, her former teacher and love interest. Both Mikage and Tsukiko use food as a means to declare their agency and reverse traditional gender roles.

The bars in these novels, and the food they serve, are now everywhere in contemporary Japanese culture. In the TV series Midnight Diner, for example, we see plenty of yoshoku. The characters, who range from boxers to Yakuza bosses, singers, strippers, pachinko parlour workers and shop workers, order these now-canonical dishes, which often have sentimental value. Today, there is the sense that this kind of food has always been a part of Japanese culture, because we think of the country as one that has a massive cultural reach but a largely inward gaze. Yet curries, katsu and ramen demonstrate the impact of the war on Japan – the change it caused and the manner in which Japan responded – all while creating a new food culture.

The weight of narrative given to food in these books might not be noteworthy to Western readers, but framed in the context of the starvation and hardship endured during the Second World War, and the radical cultural shift in the years that followed, this makes sense. For Japanese writers, whose work is so widely exported, this seems to be a way to say: Look at us; this is how things have changed for us, while also giving their characters space to move, change, reflect, fail. That all their dishes are unremarkable heightens this notion: through their presence, we get a sense of what Japanese people during this period were actually eating, a type of realism which might contravene Western interpretations of everyday Japanese cuisine, but one which is nevertheless true to life.

4. Printmaking: Edo food production in Hokusai, by Jelena Sofronijevic

Much of what we now consider to be contemporary Japanese food culture can be traced back to the Edo period (1603–1867) – the time of the Tokugawa shogunate, a military regime typified by samurai daimyo (Japanese feudal lords). The period remains stereotyped as ‘traditional Japan’, with washoku – the cuisine that was developed at this time – recognised as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2014. But despite what this singular name and award might suggest, Japanese cuisine has never been fixed – instead, it has remained constantly in flux and, much like art in Japan, it absorbs influences from across Asia and the rest of the world. No wonder, then, that it is the popular visual art of the Edo period that best traces the flows and tides of Japanese food culture.

During the Edo period, as the Japanese economy boomed, cities burst with newcomers that had new social appetites, and artists documented the burgeoning life they saw by the ocean, in the fields, and on the streets. Katsushika Hokusai was one of these artists, and is perhaps the most famous printmaker of Edo Japan. Born in 1760, towards the end of the Edo period, and best known for his monumental series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, Hokusai was an obsessive documenter of everything he saw, from passers by to fishing boats traversing the treacherous waves in the Sea of Japan.

Towards the end of his life, Hokusai’s ambition was to compile a vast printed encyclopaedia known as The Great Picture Book of Everything. For unknown reasons, the book was never published. But in 2019, 103 drawings, which would have been destroyed in the woodblock printing process if the book had been published, were unearthed, and a couple of years later displayed at the British Museum. Taken together, these illustrations provide an alternative history of the producers and consumers in Japanese food chains, and how it was individuals who were the agents in shaping cultural values and tastes through cuisine.

In one such picture, Three men brew rice wine on the orders of Yi Di, Hokusai shows three ordinary workmen following the instructions of Yi Di, one of China’s earliest rice wine brewers, in order to produce a batch for the legendary King Yu the Great of the Xia dynasty. In his characteristic fashion, Hokusai inverts the focus from the grand recipient to the producers on the ground. The result is a comic scene, where the three workers use their weight (and a rock) to crush a sack of rice grains, the juice pouring out into a gutter at the bottom to be brewed. Clinging onto the pole for dear life, they’ve even wrapped their ankles together. As Tim Clark, co-curator of the British Museum exhibition, says, ‘Hokusai manages to make it look as if it is happening right in front of you’.

Rice is central to Hokusai’s work – and like tea, this also came to Japan from elsewhere. It travelled from the regions that are today included in China, through modernising migrants who brought with them religion, plus the means and knowledge to cultivate the rice. In his work, Hokusai reveals how the production of rice wine started – not as a small porcelain cup of clear, slightly simmering Japanese sake, but the original mijiu, which was first produced from glutinous rice in ancient China around 1000 ʙᴄ before spreading across Asia, mutating into cheongju in Korea and sake in Japan.

Hokusai’s illustration hints at how ‘traditional’ Japanese methods and instruments were really foreign inheritances. But more than this, as British Museum curator Alfred Haft suggests, Japan was actively positioning itself as the preserver of ‘authentic’ Ming Chinese culture, rather than being passively influenced by or appropriating it. These prints are testament to the two-way flows of food and culture between both states.

Edo Japan is often mischaracterised as a time of severe restrictions, with farmers locked to their lands, a strict feudal class system and sakoku (an external travel ban); successive political regimes wishing to legitimise themselves as modern have often pointed to this. But Hokusai adds nuance, acknowledging the role of other cultures and traditions as part of Japanese modernity.

Take the series ‘Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road’, which charts the rise of domestic travel in Japan. We see Japanese tourists greedily savouring soba in Iwata, Shizuoka – a city now internationally renowned for its fresh white-flour noodles. In Shinagawa…, Hokusai shows three women hand-picking and stretching nori seaweed (laver) over slats, sun-drying the fronds to intensify their flavour. Travel circulated different modes of nori production. The traditional method of harvesting from wooden stakes at sea – the process that precedes that of ‘Fifty Three Stations...’ – persisted until the 1920s (when faster-growing bamboo replaced the wooden stakes to help keep up with demand). This Asakusa nori – likely named after the Asakusa (now Sumida) river from which it was harvested – quickly became an Edo speciality. It fetched a high price in the city, forcing other regions to rebrand their own nori with the Asakusa name in order to compete. As well as demonstrating China’s influence on Japan, Hokusai highlighted Japan’s own domestic foods; this series is a visual testament to rural, artisanal production, preserving, idealising, and advertising practices in the villages en route.

The drawings from this period also complicate the idea of ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage’, and the changes which were happening in the late Edo period. In the more politically subversive prints of , even the ‘immovable’ Buddhist deity Fudō Myōō is swept by the popular waves of Westernisation – a period when the consumption of meat, particularly beef, was promoted by the new Meiji government as a sign of prosperity. In the print Enlightenment of Acala, Myōō reads the government’s propaganda paper, News Magazine, redirecting his holy flames to warm his sake and beef stew instead. This blend of past and present finds its mirror today in the wagashi bloggers who tout mochi as Japan’s oldest processed food, and renewed interest in ‘traditions’ like tea ceremonies as both mindfulness practice and high art culture.

Exhibitions in Japan such as Hokusai and the Gourmets of Great Edo, Oishii Ukiyo-e: The Roots of Japanese Cuisine and the poultry market history captured at’ The Hokusai Bird Park which I saw at the Sumida Hokusai Museum this month, have done important work in showcasing the origins of Japanese cuisine. Yet outside of Japan, barring the fascination with food in Studio Ghibli films, the connections between Japanese food and visual culture remain underexplored. One exception here is Clare Pollard, curator of Japanese art at the Ashmolean Museum, who use Utagawa Hiroshige’s ‘Famous Restaurants of Edo’ series (1839–1842) to reveal how restaurants became a vital part of the urban infrastructure and sites of interclass interaction in the period.

Hokusai’s farmers; fishermen; cauldrons stoked by fire; Hiroshige’s restaurants; Kyosai’s fiery feast: all are vital clues which demonstrate how food was produced and eaten in Edo Japan. If these artists’ ambition was truly to depict everything possible, then the recurrence of restaurants, recipes, and real people across their work reinforces the centrality of food production for Japanese culture and history, speaking to the many heritages of – and continued influences on – Japan, highlighting how flux has always been central, and how its oft-othered culture is perhaps not so rigid or unique after all.

Credits

Kambole Campbell is an Anglo-Zambian freelance writer and film/TV/culture critic based in London, with written and audiovisual work appearing in Empire Magazine, Sight & Sound, Little White Lies, i-D, BBC Culture, The Independent, The Guardian, Hyperallergic, Thrillist, and Polygon and more.

Hugo Brown is a writer and editor based in London.

Jelena Sofronijevic (@jelsofron) is an audio producer and freelance journalist, who makes content at the intersections of cultural and political history. They are the producer of EMPIRE LINES, a podcast which uncovers the unexpected flows of empires through art, and historicity, a new series of audio walking tours, exploring how cities got to be the way they are.

Vittles is edited by Jonathan Nunn, Sharanya Deepak and Rebecca May Johnson, and proofed and subedited by Sophie Whitehead.

Very interesting read, could devour endless Japanese food culture content. It's a shame though that for an article exploring food "through four arts", the accompanying visuals are so limited and generally poor quality / resolution. What's the reason for this?

Another top quality newsletter, and one of great personal interest. A pleasure to read.