To Slay, or Not to Slay?

Adriann Ramirez on the tyranny of rainbow cakes and corporate Pride for queer bakers. Illustration by Gabriel Mafféïs

Good morning and welcome to Vittles! In today’s essay, Adriann Ramirez (aka Gay Nigella) explores the complicated feelings that arise every year when requests from corporations for Pride-themed bakes start to flood their inbox. (If you’re thinking, ‘But Pride is months away’, we’re publishing this piece now to coincide with LGBT+ History Month in the UK. That’s our story, and we’re sticking to it.)

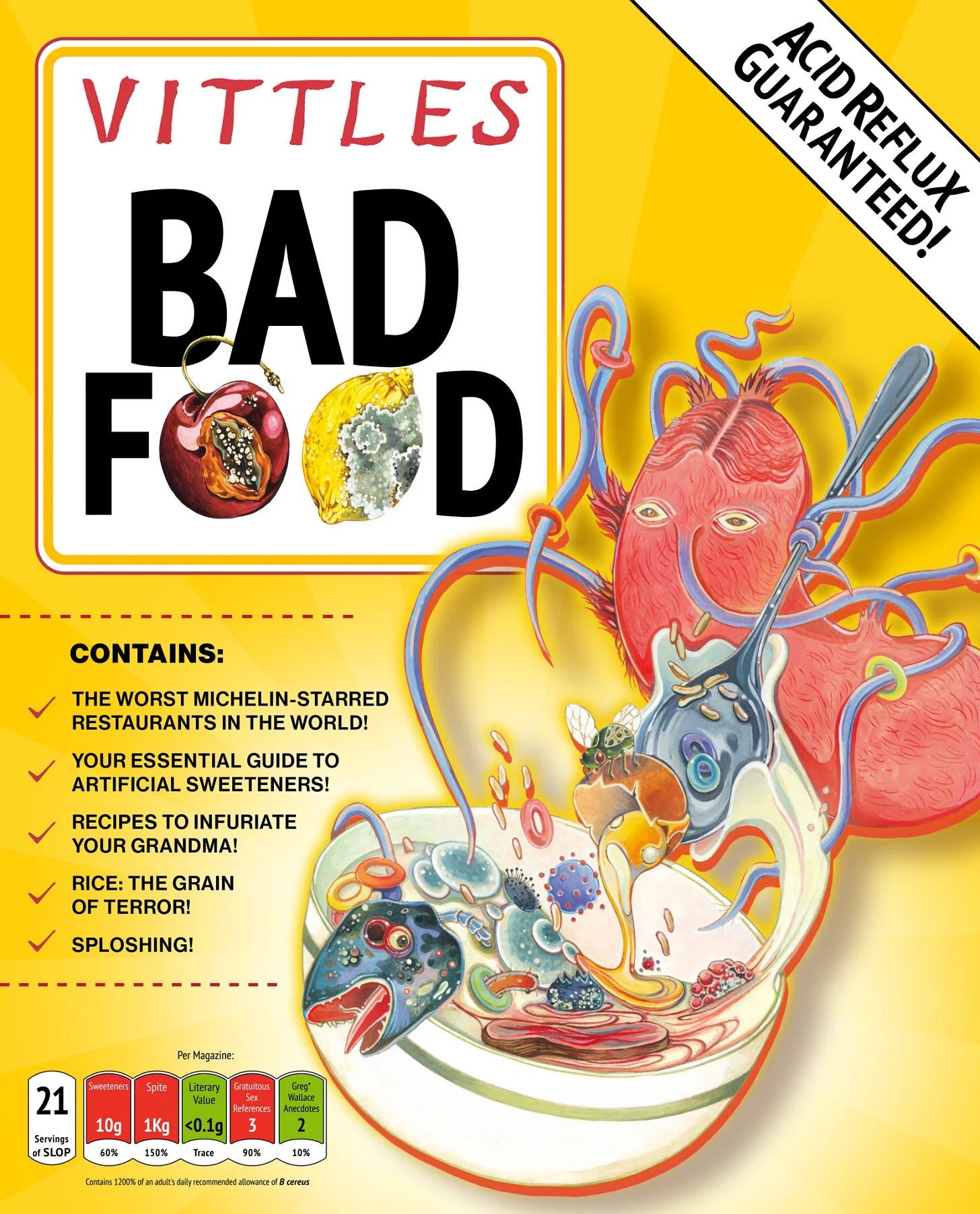

Issue 2 of our print magazine, on the theme of Bad Food, is still available and is very queer, with contributions from Johanna Hedva, Morgan Page, Alim Kheraj, Lauren J Joseph and many more. You should order a copy.

One Tuesday afternoon last June, one of the hottest days of the year, I set out on a mission: to try a slice of the Pride rainbow layer cake from Ikea. As the Head of Pastry at Fink’s in London and the self-proclaimed Gay Nigella, I felt it was my duty to try the cake professing its Pride credentials so loudly. It turned out that the only thing to feel pride about that day was Ikea’s new central London location at Oxford Circus – a dead twenty-five minutes from my door to theirs, which at least minimised the inconvenience of tasting six layers of artificially coloured vanilla sponge and buttercream. As suspected, the rainbow cake was unambiguously shit: dry, with a saccharine, cloying sweetness, lacking any real flavour or complexity. Flatpack Pride. In short: it was a fairly accurate reflection of contemporary mainstream Pride.

*

In the run-up to Pride Month every May, a slew of requests from companies I’ve never heard of fill my inbox. They’re looking for menus, quotes and custom cakes – all of which, they’re adamant, must be explicitly Pride- and/or rainbow-themed. Some queries are sweeter than others. Last year, Fink’s got a very last-minute request from a major corporation to create a menu of Pride-themed desserts. I came up with a bespoke menu, including brioche doughnuts filled with Gariguette strawberry jam and vanilla crème légère, cupcakes with buttercream made with seasonal fruit, and layer cakes (which this very magazine considered notable enough to write about), signing off my email with a, ‘While none of the desserts are Pride-themed, many queers make them, which is PRIDE plenty!’ I never heard from them again.

‘You are an LGBTQ+ owned business, which we are supporting during Pride month.’ This is the exact wording of a request I received. Supporting during Pride Month. And come 1 July? Chopped! I have an internal debate about whether to dignify these requests with a response. Being outwardly anti-LGBTQ has become increasingly acceptable once again, and efforts to exclude trans people from public spaces are being increasingly institutionalised. Am I complicit in pinkwashing if I enable a company to hold a singular Pride lunch, then happily ignore us for the rest of the year? Am I cosigning the actions of corporations who have shown us, time and again, that, when it comes down to it, they don’t have our backs? While there is no straightforward answer to this, and no one monolithic approach (thank God – if there were, all queers working in food would be forced into making rainbow cakes), it does strike me that, for the mainstream, there is a right and wrong way to go about it.

*

Last year, John Whaite – former Great British Bake Off golden boy, proprietor of Ruff Puff Bakehouse and Waitrose Weekend darling – shed his apron, along with a few more pieces of clothing and some brand deals, to pursue an OnlyFans career. (Note: the account had been up since 2022, but he went whole hog with the endeavour in the summer of 2025.) It was an audacious move. The intentional and overt sexualisation of his image was at odds with the sanitised versions of queerness that tend to populate UK media outlets, which still don’t like to acknowledge that deviant sexualities are generally premised on deviant sex (or, to put it another way, they like to separate the fudge maker from the fudge packer). Risking the loss of mainstream media and consumer support to create porn was at least somewhat subversive – and in my opinion, quite chic. What’s more, I’ve done my due diligence (I’m still wondering if I can expense this to Vittles as research) and, take it from me, the boy is blessed: think Tom of Finland meets Mr Kipling.

Unfortunately for John – and despite his significant gifts in this new career strand – it has been a tumultuous and very public journey. He went from giving interviews about his refusal to be censored (alongside photoshoots demonstrating this point) to dramatically U-turning. In September, he left OnlyFans completely, crediting his work at Ruff Puff with giving him ‘a true sense of purpose again’; a few weeks later, he announced that the real reason for his departure was steroid addiction (although he is now back on OnlyFans and has closed the bricks-and-mortar bakery).

‘sanitised versions of queerness … tend to populate UK media outlets, which still don’t like to acknowledge that deviant sexualities are generally premised on deviant sex (or, to put it another way, they like to separate the fudge maker from the fudge packer)’

While I haven’t dipped my toes in the waters of public exhibitionism via OnlyFans, John’s experiences have made me question how I fit into the greater landscape of food, commercial or otherwise. Am I, like John, only acceptable to the media and corporate powers that be when proffering commodified, acceptable versions of queerness that fit the narrative they want to put forward? In terms of my visibility as a queer chef, I don’t believe I have much choice in the matter of how I present myself – the last time I was mistaken for straight was when I was thirteen, and even at the time that was a shock. Now, rarely does a day go by where I’m not clocked for being the fag I am; I suppose the short shorts and long, painted nails are a dead giveaway. But for me, it’s important to be perceived as queer – it feels vital.

I was recently asked to be a guest chef on Sunday Brunch. I thought long and hard about what I was going to wear. I wanted to be authentic to myself and also let it be known on national television, to Barbara in Sheffield or Mickey in Shrewsbury, that I was queer (and unapologetic at that), but I didn’t want to wear something flashy and brightly coloured. I opted for a simple outfit: navy high-waisted trousers, a cropped white tee and a dark grey cardigan slung low on my shoulders, finished off with six-inch olive-green platform boots and terracotta blush on my cheeks – from Rhode, no less. The response to my outfit and appearance was largely positive, though someone on Twitter did ask what that bloke had on his feet. Fair play to him. Sunday Brunch did, however, send a list of things I wasn’t allowed to do, such as swearing, using innuendo or glamourising drinking, and while those things aren’t necessarily inherent to queerness, some of them do make it a whole lot more fun. I managed to fare well without breaking any rules, have a nice time and look hot while being the only queer among a group of lovely – but deeply heterosexual – guests and hosts. I was asked back. While it may not have been radically different from the queerness we’re used to seeing in the mainstream, it did make me feel that maybe there was space for someone like me.

*

At Fink’s, over 50% of staff company-wide are queer. On one level, managing our team is not dissimilar to a workplace with a majority of heterosexual chefs: there are arguments; people become close; there are romances and dalliances; close bonds are formed and broken; and really good food is created and cooked. That part is universal. However, to have the shared language that comes from being queer, with people you work with so intimately, is special. I was recently speaking to a newer colleague who told me that, in her two years working at a catering kitchen before joining Fink’s, she’d never once mentioned that she was gay. I found that shocking, but maybe it’s not.

Throughout my eleven years in the food industry, encompassing both front- and back-of-house roles, I’ve experienced a bevy of homophobic treatments. In service kitchens, the male chefs and kitchen porters made sexually suggestive jokes at my expense, groped me, and were outright homophobic. While this sometimes made me feel small and could be intimidating, I didn’t let it deter me. I learned to use my queerness as a weapon of its own. Firstly, I learned how to cook, and I learned how to do it better than them. My knowledge of ingredients and provenance, plus my unique relationships with suppliers and other great chefs in the field, gave me an upper hand – or, at the least, evened the playing field. Secondly, my wit got sharper. I stopped letting myself be made fun of, and I began to make their heterosexuality the butt of the joke. It confused some and made others back off. Sometimes it meant people didn’t take me as seriously in those spaces, but that was a price I was more than happy to pay.

‘I was recently speaking to a newer colleague who told me that, in her two years working at a catering kitchen … she’d never once mentioned that she was gay’

My body, my clothing, my appearance, my humour, my sexuality, my work as a pastry chef. All of it is wrapped up in a messy package, tied with pink satin ribbon. Queerness, in its essence, is a bittersweet experience. I am shaped by the smoke that filled every corner of the room after offal was grilled over hot coals when I worked as a server at Black Axe Mangal, and by the delicacy of the petals that adorned the cakes when I worked as a personal assistant and sometimes-baker at Violet Cakes. My queerness is now in the juxtaposition of the bitter and the sweet that I bring to my baking and leadership at Fink’s. It is always difficult to choose to be the most authentic version of yourself: it can alienate you from family, friends or colleagues. There’s always something to lose, but when you realise the biggest risk is losing yourself, it’s important to take the chance. And finding your people is special and so affirming. My queerness is the sword by which I die, and also, it is what I use to defend myself, to cut out the niche I occupy as a pastry chef and human.

Compromising in this life – capitalist or otherwise – is currently necessary in whatever career you choose, so depending on the commission and how good the money is, there’s a pretty good chance I’ll help you out (although I do have my hard nos: J K Rowling and anyone who denies the genocide in Palestine can get fucked). I won’t fulfil your idea of what a queer baker should make for Pride, but I will use the best damn ingredients I can find, decorate it tastefully, make something you’ll actually want to eat and charge you appropriately for what it’s worth. Ultimately, I’ll give you what you want, but it’ll be on my terms. I defend the rights of queer people wanting to get their bag and take the money of people looking to pinkwash. I defend the right of John Whaite to show his ass off while also continuing to be a successful and talented pastry chef (famously, the two are not mutually exclusive – I mean, look at me).

I even defend those queer bakers who willingly choose to make shitty rainbow layer cakes because they like them! I’m optimistic that there’s space for all of us. I’m still wondering where exactly I fit into this system, but maybe I don’t need to have it all figured out. If I’ve learned anything in my decade of being in the industry, it’s that authenticity is what strikes the deepest chord with most people. The path less travelled is harder but often more rewarding, and you might even find a rainbow at the end of it – or a slice of rainbow layer cake. But please, do not ask me to make you one.

Credits

Adriann Ramirez is the Head of Pastry at Fink’s London and a multidisciplinary artist whose work expands across writing, performance, dance, filmmaking and food writing. Their debut book of poetry and photography titled, Hot Tears Through Velvet Rage, was published in 2021 by Polari Press.

Gabriel Mafféïs is a Paris-based freelance illustrator and comics artist. Through colorful, narrative images, he creates scenes where imagination and reality overlap, exploring themes of community, identity, and relationships.

The Vittles masthead can be viewed here.

Further Reading

Hannah Levene on the role of food in lesbian feminist literature

Waithera Sebatindira on the erotic and emancipatory potential of the Eucharist

Francesca Wade on the Alice B. Toklas Cook Book

A fantastic read!

Reminds me of Jenny Lau’s wonderful article and all the ‘Tang Jackets’ being hawked all over Instagram by every brand and their lazy creative director™️. I wonder who amongst us is yet to feel their identity commodified, and if we aren’t, do we even have any worth to western capitalism anymore?