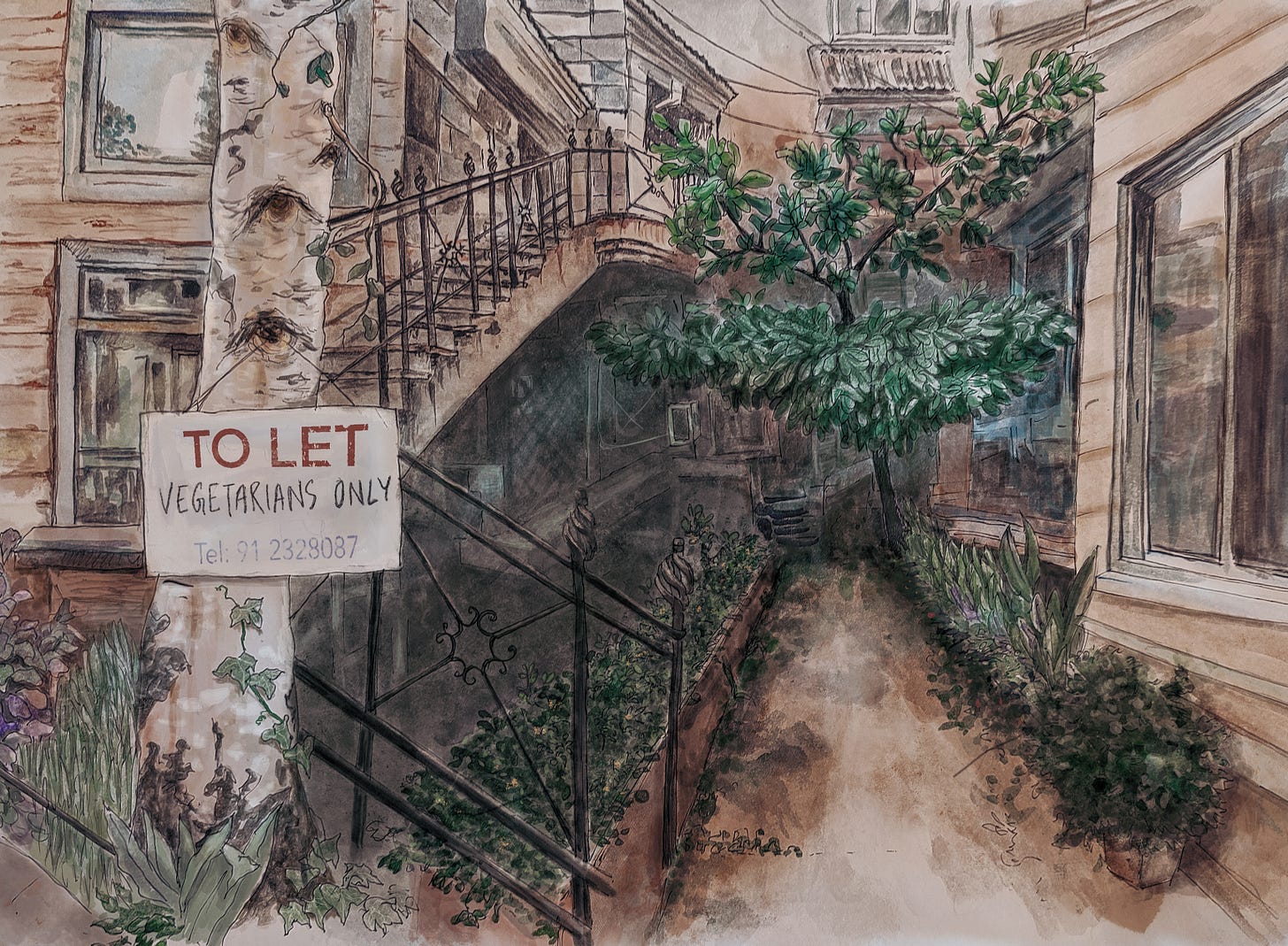

Vegetarians Only

In India, diet-based surveillance prevents Muslim citizens from finding secure homes. Words by Sara Ather. Illustration by Asfa Sabrin.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles. Each Monday we publish a different piece of writing related to food, whether it’s an essay, a dispatch, a polemic, a review, or even poetry. This week, Sara Ather writes about dietary surveillance by landlords and real-estate agents in India, and how, under the Hindu-nationalist BJP, meat-eating is used as a litmus-test for belonging, preventing Indian Muslims from finding places they can call home.

If you wish to receive Vittles Recipes on Wednesday and Vittles Restaurants on Friday for £5 a month, or £45 a year, then please subscribe below – each subscription helps us pay writers fairly and gives you access to our entire back catalogue.

Vegetarians Only

In India, dietary surveillance prevents Muslim citizens from finding secure homes. Words by Sara Ather. Illustration by Asfa Sabrin.

In December 2023, Anam, a single Indian-Muslim journalist, found her ideal home in South Delhi. It was on the third floor of a modern building in a moderately upscale neighbourhood, equipped with a lift and close to her workplace. Anam was excited about the balcony, a space where she could sit after a long day of work – a luxury in a densely packed city like New Delhi, where the streets belong to men and balconies can be a refuge for women. This spot, she thought, could be her sanctuary, perhaps even to host friends and serve them her favourite chicken and fish dishes. Her excitement waned after a conversation with her prospective landlord, when she was asked, ‘Do you eat non-vegetarian food?’ Taken aback, she admitted that she did. ‘But if it’s a problem, I can avoid cooking it here’, she said, ready to make any concession necessary. When we spoke, Anam recognised the desperation she had felt when she thought of compromising on her diet for the flat. ‘I had started to imagine my life there, planning how I’d manage without cooking my usual meals, but it would have forced me to adopt a way of life that I cannot call my own,’ she said.

While Anam’s is a personal story, it is not an isolated incident. Aqsa, an artist who lives in Mumbai told me that house-hunting was long and arduous, and a ‘rough ride’. She finally found a flat she liked with three Hindu friends, but her neighbours lodged complaints about chicken bones that they saw in the trash. ‘The next day, our landlord came over and lost it when he found out I was Muslim,’ she said. The same week, Aqsa and her flatmates left the property, concerned about her safety. In another conversation, Zara, a Muslim woman who also lives in Mumbai, told me about how once, her neighbour complained about previous Muslim tenants in their apartment complex, mistaking her for Hindu. ‘She said that they “polluted the entire atmosphere with their strange-smelling food and unhygienic living conditions; the entire building reeked of it”.’ To Zara, who considered the woman to be friendly, this was a shock. ‘I felt both endangered and degraded. At once, I knew I couldn’t belong there.’

For Indian Muslims like Anam, Aqsa and Zara, these experiences are extremely commonplace. Even though it is against the law to exclude potential renters because of their background, real estate agents and landlords - who are often dominant-caste Hindus - use diet as a way of refusing homes to Indian Muslims and other people from historically meat-eating communities. (Although this article examines the effects of this surveillance on Indian Muslims, these methods are also used to exclude citizens from oppressed-caste and indigenous communities, and also those from India’s Northeast.) The concept of ‘purity’ that is embedded in the Hindu caste structure – espousing vegetarianism and demonising meat, especially beef – is consistently used to enforce hierarchies and to control the movement of Indian Muslims, preventing them from finding comfortable homes. In 2021, Mohsin Alam Bhat reported that a Hindu broker in a suburb of Mumbai found that ‘the right way to refuse people’ was to ‘simply [tell them] that he only has houses for “veg families”’, while a recent study found that being a meat-eater or ‘non-vegetarian’ made house-hunting a significant challenge for people moving to a new city. Over the last few decades, the policing of tenants has also extended into the online realm: Facebook groups frequently include dietary requirements in their listings, subtly discouraging Muslim applicants from searching for a home in neighbourhoods of mixed faith.

While segregation and surveillance have long been experienced by the poor and marginalised communities in India, for Indian Muslims, housing discrimination is not caste or class-specific. Even though working-class and marginalised-caste Muslims are doubly affected, this scrutiny impacts Indian Muslims across the board. It takes place in bastis (informal settlements) and smaller towns, but also in big cities and upscale neighbourhoods throughout urban India. Across cityscapes, signs proclaiming ‘No Non-Veg’ and ‘Vegetarians Only’ are as prevalent as the clustered buildings themselves. This combination of pre-emptive measures has created a language of exclusion and a system of ghettoisation that is constantly at play.

While social codes of exclusion have always existed in India, in the last decade, the rise of far-right Hindu nationalism under the Narendra Modi-led BJP has brought practices of discrimination into the mainstream. Denying Indian Muslims citizenship and dignity is a key priority in the BJP’s politics, and under their government – with support from the right-wing paramilitary outfit, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) – anti-Muslim pogroms and policies have taken over the country. The government has implemented various laws to demonise cow slaughter, and the selling and eating of beef, as ‘anti-national’ and a threat to the nation’s Hindu supremacist fabric, endangering those communities (working-class Muslims, and citizens from indigenous and oppressed-caste communities) whose livelihoods depend on the trade. Indian-Muslim communities are forced to self-censor throughout Hindu festivals; during the Kanwar Yatra, for example, butchers were forced to close or cover their shopfronts to ‘avoid hurting [Hindu] religious sentiments’, which is an excuse often employed to admonish Indian Muslims for simply practising their trade.

Even though severe acts of violence related to beef justifiably capture headlines, the more insidious ways these developments infiltrate the daily lives of Muslims remain largely underexplored. Across India, mob lynchings of meat-sellers and traders by Hindutva vigilantes are so common that there are now specific terms – ‘beef lynching’ and ‘cow vigilante violence’ (as many of these attackers operate under the pretext of religious ‘cow protection’) – to describe them. A vast majority of those killed in these attacks are Indian Muslim; since June 2024 alone, there have at least six such lynchings, like the killing of Afan Abdul Ansari in Nashik, Maharastra. Akash Bhattacharya, a historian and political activist, notes how these incidents have escalated majorly since the BJP’s rise to mainstream politics. ‘Since 2014, the spate of beef lynchings has instilled widespread fear around non-vegetarian diets. Culinary discrimination has now been codified into law, with laws like the Haryana Cow Protection Act [which prohibits the slaughter and skinning of cows, a livelihood for many people in marginalised communities] that was passed in 2015.’ Bhattacharya tells me that this law was ‘deliberately enacted to polarise communities and justify violence against Muslims based on their dietary habits’. The selective targeting of meat (and particularly beef) sale and consumption shows a broader, more sinister agenda by the majoritarian regime, and a strategy to redraw the social and cultural boundaries of India, dividing them by class, caste, and faith.

Muslims are also forced to live in segregated corners because of their food choices, only to have those areas come under intense scrutiny for the very same reasons they were segregated in the first place. In these circumstances, ‘punishments’ for meat-eating often include the bulldozing of entire homes in neighbourhoods. On 15 June 2024, for example, eleven Muslim-owned homes in the tribal-majority Mandla district of Madhya Pradesh were razed, allegedly as a part of a crackdown on illegal beef trading. Renting and buying homes for Indian Muslims has become more difficult than ever as well. Nazima Parveen, a Delhi-based research scholar explains how ‘Muslims are often compelled to pay a premium to purchase property in mixed localities, while their selling prices are devalued due to a lack of interested buyers, compounding the challenges faced by them in securing homes outside designated segregated spaces’. A small number of benevolent, secular-minded, and understanding landlords mean that finding a home is sometimes possible, but these are exceptions rather than rules. And even then the scrutiny continues. These repeated acts of diet-based discrimination eventually become a part of everyday life for Indian Muslims, in which the seclusion of spaces, and their consequent isolation, becomes a condition of the mind. Aliza, a Mumbai-based journalist told me that ‘This constant vigilance around food signifies the pervasive fear and discrimination Muslims face in cities. We’re always walking on eggshells.’

Ali, a graphic designer based in Navi (New) Mumbai who was rejected from multiple housing applications on the pretext that his family were ‘meat eaters’, points out how during Muslim festivals like Bakr-Eid (or Eid Al-Adha, a festival that involves a ritual of sacrifice), surveillance becomes heightened – even in close-knit, mixed neighbourhoods. In 2023, a Muslim family in a mixed housing complex were scrutinised for keeping two goats in their home, even when they clarified that the ritual of qurbani (sacrifice) would take place in a designated area, away from the complex. And during the same festival in June this year, several people from the Jain community in New Delhi raised Rs 1.5 million and disguised themselves as Muslims to buy over a hundred goats from a Muslim vendor; they claimed to be ‘saving [them] from slaughter’. (The Jain community prides itself on religious purity through its practised vegetarianism and has the support of the ruling BJP. Its members often call for bans on meat, ironically, on the grounds of ‘secularism’. Most recently, these bans have established the world’s first ‘vegetarian city’ in Palitana, Gujarat, also the Prime Minister’s home state. )

Meanwhile, on the days preceding Bakr-eid this year, images from right-wing accounts showing sacrificial blood flowing into the streets flooded the internet – an attempt to portray the festival as barbaric. Yet these claims avoid questioning why these spaces where working-class Muslims live have no municipal facilities like adequate drainage to conduct rituals, or even other daily activities, in a safe and clean way. These practices help to create an image of Muslims as a community that embodies savageness and impurity, in line with the political ambitions of Hindu nationalists. They are used to further alienate Muslims, who are not only deemed different, but also fundamentally incapable of merging with the ethos of the majoritarian nation-state.

These formations and developments have had a profound impact on the perspectives of Indian Muslims today, influencing how their future in the country is envisioned. There is the experience of almost belonging to a place, of living in it and yet knowing it only from a distance. At the end of the day, can you really feel at home in a place where there is perpetual scrutiny? In popular discourse, the segregation of Muslims in ghettos and separate neighbourhoods is often written off as a self-imposed practice. However, these structures have not emerged purely by choice: while there isn’t any explicit legal directive that prohibits people from different religious backgrounds from living together, neither are there laws that protect vulnerable people who face discrimination simply for how they live. Within these social codes of surveillance, everyday life in India is imbued with the way of thinking that was once specific to the conditions of riots. These are attempts, sponsored and set in place by the state, to make an entire community feel that they do not belong in any place – not even their segregated ghettos. Even as meat-based dishes like biryani and kebabs – owing to India’s Muslim history and present – are widely consumed and celebrated, the people who prepare these foods are relegated to the margins.

When I researched this essay, I observed that almost every Indian Muslim I spoke to had experienced this sort of discrimination. I talked to people who had given up studying at their university of choice, and others whose secure futures, promised by a new job, collapsed in an instant of them arriving in their new city. For young Indian Muslims, these are everyday negotiations: political isolation and the loss of dreams, big and small, are defining parts of life. ‘How can I convince my parents that I should travel far away from home?’ a young woman from Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh, told me, referring to her wish to move to Mumbai to study. ‘How can I ask them not to worry when they watch the news of hate crimes against Muslims happening every day?’ As for Anam, after months of searching, she finally found a flat she could move into in a middle-class building in Delhi; ‘the place is nice, too,’ she said, even as she misses the instant comfort of the earlier apartment, especially the balcony that she wanted. But at least in this flat there is no one watching what she is cooking in her kitchen, or inspecting what she is throwing in her trash. A small relief.

Note: Some names have been changed to protect identities.

Credits

Sara Ather is an architect, columnist, and an incoming PhD candidate of architectural history at Cornell University.

Asfa Sabrin is an Indian artist. You can find more of her work here.

The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

Many states in India, especially the ones ruled by the BJP have laws that stem from this. It’s a form of Apartheid backed by the state.

Last night I drove past an apartment building with a big sign that read "A BRAHMANICAL HOUSING COOPERATIVE." I think the thing about housing discrimination here that has surprised me the most is how open it is, how utterly obvious and shameless.