Who Makes the Rules?

The disobedient history of Pakistani sushi by Sanam Maher. Photos by Noorulain Ali.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles. In today’s special newsletter, we are sharing the second article from Issue 1 of our new magazine, a long-read by Sanam Maher on how sushi took over Pakistan, with photos by Noorulain Ali.

Issue 1 of our magazine is still in stock and you can order through our website here. If you would like to stock it at your shop or restaurant, please order via our distributor Antenne Books by emailing maxine@antennebooks.com and mia@antennebooks.com

When the seventeen-storey Avari Towers opened in Karachi in April 1985, it was the tallest hotel in the city. ‘It felt other-worldly,’ said one chef who worked there when he was a teenager. ‘It was there that I saw a swimming pool for the first time,’ he remembered, ‘and swimsuits.’ By December 1986, this $32 million building had another novelty to offer – Fujiyama, a Japanese restaurant at its summit, named in honour of the famous peak. For the first six Saturdays of that month, eighty of Karachi’s most powerful residents were hosted for a complimentary lunch party at the restaurant’s soft launch. There had been no advertisements for Fujiyama, and for those six weeks, the only way to get in was with an invite; these began to land in the homes and offices of the city’s bankers, businessmen, doctors, and other members of Karachi’s elite. By the new year, the restaurant was so busy it had waiting lists. There were now two kinds of people in the city of six million: those who had tried sushi and those who had not.

In the late eighties, a Japanese restaurant like Fujiyama was an expensive proposition: foreign chefs had to be hired, staff trained, and ingredients from wasabi to rice constantly imported. Sushi – raw fish – in a country where daal roti is a staple and vegetables are often cooked down until they lose their crunch. Who would take such a risk? And yet, somehow, it paid off. Fujiyama was the first place to serve Japanese cuisine in Pakistan, and it was where many Pakistanis encountered sushi for the first time.

Today, you can open your fast at a sushi buffet during Ramadan or host a wedding reception for a small (by Pakistani standards) gathering of a hundred or more at a Japanese restaurant. In Karachi, the most popular sushi reflects how the Japanese cuisine has been adapted for a Pakistani palate: deep-fried spicy prawn tempura rolls, crispy California rolls, and a chicken roll with garlic fried rice and spicy mayonnaise. When restaurants closed during the pandemic, waiters zipped across the city on motorbikes to deliver sushi. In May 2022, the cash-strapped government attempted to impose a ban on the import of ‘luxury items’ to Pakistan – including Norwegian salmon and nori from Dubai – but the finance minister later had to admit that ‘even though we had the ban … you could still find salmon and sushi in restaurants.’

While much of it may not be good – with gummy rice or chalky, bland wasabi – it’s clear today that Pakistanis want sushi. It is on the menus of fine dining restaurants in hotels, and in the many pan-Asian restaurants that have mushroomed across Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad. By the time I encountered ‘chapli sushi’ (a chapli kebab and cucumber maki roll) at a restaurant in Lahore, I wondered: How did we get here?

In order to understand the risks associated with bringing an expensive novelty like sushi to Pakistan, you have to understand the men of the Avari family. They were entrepreneurs – hustlers, really – of a kind we rarely see in present-day Pakistan.

Byram Avari – ‘Baba’ to employees of the Avari hotel chain and Fujiyama – lived by the same simple edicts as his father Dinshaw. A Zoroastrian migrant from Bombay, Dinshaw moved to Karachi as an insurance agent in 1929. ‘Rules are made for fools, and donkeys and mules, and children in schools,’ Dinshaw liked to say. Who makes the rules? You and I. Who can amend the rules? You and I.

In 1945, Dinshaw bought Karachi’s Bristol Hotel, which had until then been under the private management of Englishmen. However, as soon as the sale went through, the hotel was requisitioned by the army. Dinshaw approached Revenue Commissioner Sir Sidney Ridley, a friend from the Rotary Club, to intervene. Dinshaw wanted his hotel back – he had used all his savings and borrowed money to pay the Rs100,000 purchase price. ‘How can a bloody Indian run an English hotel?’” the provost marshal asked Sir Ridley. However, when Dinshaw said that he would reduce charges for lodging, the hotel was derequisitioned. Who can amend the rules?

Dinshaw was clever: he reduced the rates but doubled the charge for one peg of whiskey, then paid a sergeant Rs1 commission for each soldier sent to stay at the Bristol. Rooms were filled with up to six soldiers at a time. When Dinshaw saw that soldiers were stealing his imported crockery and ashtrays as souvenirs, he stamped them with ‘Stolen from the Bristol Hotel’ and put them up for sale. They were a hit. Dinshaw made back his Rs100,000 payment in the first year.

In 1947, right before India was partitioned, Dinshaw stood on Chinna Creek in Karachi and imagined a waterfront resort hotel on its marshy sands. There were many stories about the spot, like the time in April 1930 when Gandhi set out on his Salt March to protest British rule in India and Congress volunteers gathered salt from the marshes in solidarity (the salt was ultimately declared unfit for human consumption when several people who ate it ended up in hospital). At a reception for Lord Mountbatten in the days before partition, then-Chief Minister of Sindh, Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah, introduced Dinshaw to the viceroy thus: ‘Excellency, please meet the madman who wants to build a hotel where even the dogs won’t go, and who will later commit suicide in the creek next to it.’

‘Rules are made for fools, and donkeys and mules, and children in schools,’ Dinshaw liked to say. ‘Who makes the rules? You and I. Who can amend the rules? You and I.’

But Dinshaw was no fool. To stand out, he offered something different, and even though the creek-side hotel was on the outskirts of the city, patrons were curious enough to go. Beach Luxury Hotel opened on 21 March 1948, and its advertisements boasted that ‘There are 13 “A” class hotels in Karachi, but only one of them – Beach Luxury – is by the sea!’ Government officials dined there after meetings about the exchange of commodities between the newly partitioned India and Pakistan (an advert in 1951 declared that ‘All those who matter go to the Beach’). In the decades that followed Pakistan’s independence, the Beach became the place of New Year’s Eve balls, garden dinners (accompanied by European orchestras) and, by 1962, a nightclub named ‘007’ in homage to the newly released Dr. No. The thirty-five-room hotel, with its scenic palm-fringed waterfront gardens, was the site of many marriage proposals.

In certain quarters, a whiff of disapproval lingered over every one of Dinshaw’s new schemes. When he introduced the concept of buffet-style meals for guests, some papers wrote that he was making people eat like cattle. But, as Dinshaw, and later, his son Byram, would say, ‘A leader leads the pack.’ These edicts guided the Avari men as they took chances. They believed their ideas would catch on.

This is why, when Byram found himself mesmerised by a chef’s theatrics at Benihana, a Japanese restaurant in Hawaii in 1986, he trusted his intuition. A similar restaurant at the top of the new Avari Hotel would be a great draw, he thought. ‘It’s Japanese kat-a-kat!’ Byram’s teenage son Xerxes said with delight as he watched every flipped shrimp and silver flash of a knife. Even so, common sense dictated that raw fish would never be accepted in Pakistan – even Xerxes shrank away from the nigiri at Benihana. But Byram was determined, and travelled with his wife Goshpi to Dubai, Singapore and Hong Kong, where they ordered Japanese food for breakfast, lunch and dinner every day.

Over time, Byram’s notebook filled with names of dishes and notes on their presentation. ‘I was very excited,’ he said to me in 2022, ‘and more than that, my father was very excited and very happy.’ There was no doubt in the pair’s minds that this would succeed, because they knew what they were promising their customers: something niche, something to brag about. ‘Whenever we held French or Belgian food festivals at the Beach Luxury or the Avari Hotel, we would get quite a crowd,’ Byram explained. And it didn’t matter that customers may not have been familiar with the food. ‘You see, they wanted to say, “I went to the Avari for some French food”. It was a status symbol. A fancy thing to do.’

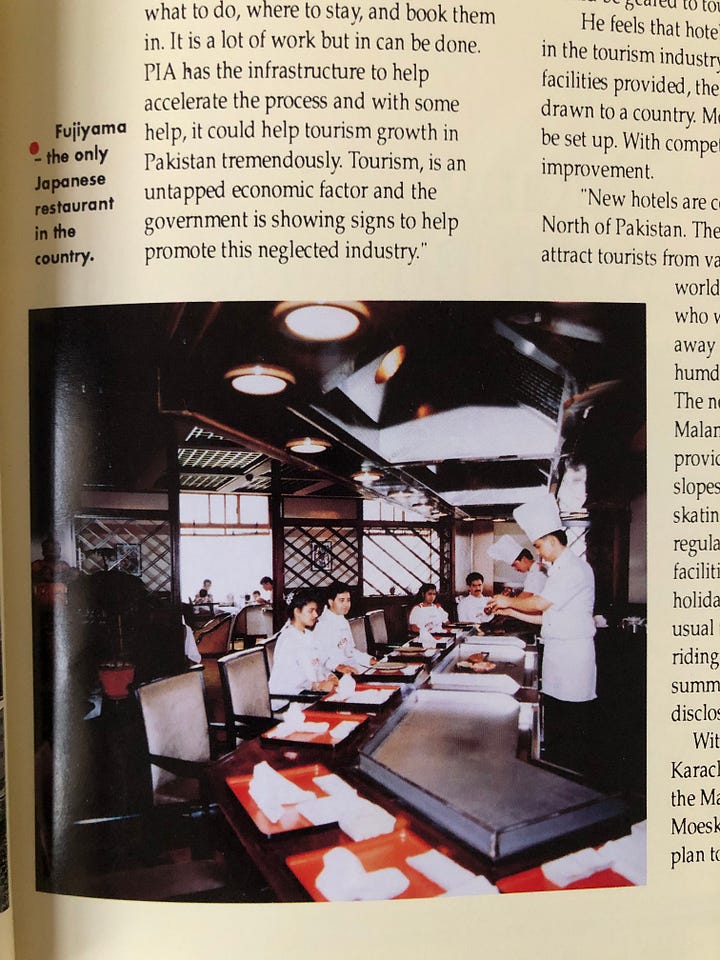

Byram wanted Fujiyama’s interiors and the quality of the food to match the aspirations of the customer. He poached a Japanese chef, Keni Hara, from a hotel in Dubai, and an interior decorating firm in Bangkok was hired to design the space. There were three teppanyaki counters, and the restaurant was intimate and dimly lit, keeping the city’s harsh sunlight out. It had soft pink linens, dark wood furniture, marble flooring, trellis partitions and a gently burbling water fountain. A private dining room with curtains offered discretion. Waiters were hired and training commenced at the Avari Towers. ‘The chef’s wife, who we called Momo, taught us,’ Vincent Francis Rodrigues, one of the waiters at the time, recalled. ‘We learned about ojigi – bowing – and how to hold chopsticks, so we could show the guests.’ The chopsticks had a little fixture at the top so they were as easy to use as tongs.

The servers had to try the food so they could guide guests. Chef Keni offered sashimi. ‘Kachhi machi?’ the waiters asked, and some refused to eat the raw fish. Vincent had never tasted anything like it. His Goan family regularly made prawn curries or fried surmai; white and black pomfret; mackerel and sole. But this? It was at once salty and a little sweet, a soft yet yielding bite that made his eyes water. The servers were sometimes given leftovers from large banquets or weddings, and they would have relished the tender meats and barbequed chicken. Many of them would have wondered if the raw food was even halal, but to turn it down could mean losing the opportunity for work. Chef Arshad Mehmood, now forty-seven, started his career as a sixteen-year-old banquet waiter at the Avari. On his first day in the Pakistani banquet kitchens, he was given forty kilograms of onions to dice. When he was moved to the Fujiyama kitchens, he was carving rosettes with cucumbers and carrots. He saw a pink fish – salmon – for the first time. Why give that up? When Chef insisted he eat tuna sashimi, Arshad closed his eyes, read the Durood Sharif and put it in his mouth. Momo taught the waiters to make table-side shabu-shabu and sukiyaki. Arshad showed me the sketches he made as he learned to plate meals. He matched the Japanese names of dishes to Urdu words to remember them: teriyaki was ‘tarri’, the gleam of the sauce like the film of oil skimming a saalan.

‘When Chef insisted he eat tuna sashimi, Arshad closed his eyes, read the Durood Sharif and put it in his mouth’

For the first six weeks, there was a set menu, and Byram, Goshpi and their sons would go from table to table, chatting to their guests. This was just a taste of what was on offer, and Vincent remembers that despite the high prices, the restaurant was often booked out once it opened to the public in January 1987. Fujiyama’s windows looked out onto the great expanse of the city, but its noise and heat and crowds were a world away, because up here was something totally different to anything you could find out there. In this room, you would learn that a sliver of sheer pink ginger cleansed your palate so you could appreciate the difference between the Norwegian salmon and the sweet crab. Byram found that people sitting in the private dining room would request for the curtains to be opened so they could ‘see and be seen’.

‘If you can’t go to Fujiyama, you can’t talk sushi and wasabi and gyoza,’ said Ayaz Khan, who worked as a Food and Beverages Manager at Avari Towers a decade after Fujiyama opened, and is now the proprietor of Okra, one of Pakistan’s best restaurants. A demand had been created. A leader leads the pack.

In the thirty-eight years since Fujiyama opened, sushi has gradually gained popularity and adapted to Pakistani culture. In 2001, Chef June Gallo joined Sakura, one of the top Japanese restaurants in Karachi, and found that staff were throwing away salmon roe, bought for £140–160 a kilo, because it expired before it was ever ordered. Customers did not know what it was. The Sri Lankan chef who had previously run the kitchen had trained in Japan for four years, and at Sakura he diligently recreated the simple, fresh flavours he encountered there. But customers complained: the food was bland. When that chef resigned, Chef June began to experiment. He tempered everything with red chilli powder, sugar syrups, soy, tabasco and togarashi. Octopus and lobster were taken off the menu. Sakura went from forty covers a night to sixty, and then up to 180 – all in the space of three months.

Today, customers in Pakistan’s major cities do not have to visit fine-dining restaurants in hotels to get sushi. While we don’t have the grab-n-go maki of convenience stores or the bright plates of nigiri rolling by at sushi train restaurants, the chefs at upscale sushi restaurants – most of them Filipino – have taken recipes with them as they move from one establishment to another. This means that the garlic rice you pay Rs1290 (£3.70) for at Sakura can now be eaten for Rs620 (£1.80) at Cocochan, a pan-Asian restaurant in Karachi. The difference is the quality of ingredients (is the wasabi from Japan, or is it a powder from Dubai?). Some spots even try to lure customers with novel experiences: is your sushi brought to your table, or does it arrive – as at the Karachi-based restaurant Nori – on a ‘sushi boat’, bobbing along a makeshift river? At Chop Chop Wok, a chain of restaurants modelled on Wagamama (down to the menu’s design), the salmon nigiri and sashimi are the priciest dishes on offer, and sushi will often be ordered as a side dish alongside the popular Korean fried chicken or crispy beef with broccoli.

‘Byram found that people sitting in the private dining room would request for the curtains to be opened so they could ‘see and be seen’’

As sushi has become ubiquitous at mid-tier restaurants in Pakistan, high-end ones are seeking new ways to maintain its allure. At Sakura, for instance, select dishes have been named after special requests by loyal customers. There is the ‘Asif Maki’ (beef, wasabi, crushed peppers), the ‘Amna Maki’ (salmon, crab, cucumber, teriyaki and spicy mayonnaise), and the ‘Hameed Haroon salad’ (gomuku salad with tuna, pickles and a wasabi dressing). Meanwhile, Karachi-based fine-dining restaurant Izakaya caters to the kind of customer Fujiyama may have attracted in 1987: moneyed, and seeking experiences that make for good cocktail-party stories. Until recently, Izakaya was accessible solely to members – who could only join through another member’s reference – for an annual fee of Rs100,000 (and this did not include meals).

Izakaya, which opened in 2022, is all marble floors and designer furniture, with pieces from Art Basel and Japan. Each of the six rooms follows a theme. There’s the ‘Shah Room’ with a baroque chandelier hanging low over the table, while the secret ‘Polo Lounge’ reveals itself behind a bookshelf. Each room has a dedicated server, private music system, butler, and chef. In its first year, Izakaya had a hundred members, including corporations. Among customers here, eye-watering prices are welcomed. Anyone can pay Rs4700 (£14) for nine pieces of salmon nigiri at a pan-Asian restaurant; only a select few can drop Rs36,000 (£103) for the twenty-course ‘experience’ at Izakaya’s omakase bar.

This is what Izakaya’s proprietor, Mustafa Sardar, told me when I visited his restaurant to try and understand the allure. Thirty-one-year-old Mustafa is the grandson of the singer Madam Noor Jehan, and a graduate of Le Cordon Bleu. When we met, he was dressed in a pristine cream shalwar kameez and black Hermès slides. Izakaya is located in a residential neighbourhood, and there is no sign outside. A house across the street displays angry signs reminding people that commercial activity is not allowed in such a neighbourhood. But if you know the right people and have enough money, a sign is easy enough to ignore, with several thousand rupees slipped into the palm of a policeman or city official so they turn a blind eye.

At Izakaya, the food is secondary. ‘[Of] the people that have the money to come here, 95% of them don’t know what a Michelin star is,’ Mustafa said. He has served truffle foam only to have customers query, ‘Ye jhaag kya hai?’ (‘What is this foam?’) Give them tuna sashimi and they say, ‘Thora saa jalaa do’ (‘Char it a bit’). I asked Mustafa if this was frustrating. ‘I miss being around people who like food,’ he said. ‘But I like money. You want fried rice? I don’t give a shit. I’ll make you fried rice.’

I asked about Mustafa’s earliest encounters with Japanese food. As a teenager, he would visit Sakura after school to have lunch before tuitions. ‘I’m hella spoiled,’ he said. As a freshman at college in the US, he flew to Mykonos for a break and encountered ‘food theatre’ at NAMMOS. There was drama to the whole thing: chefs presenting him with knives to cut the Angus beef, the still-wriggling fish displayed before it was salt-baked. ‘That’s what Izakaya is,’ Mustafa explained, ‘an experience’.

Izakaya was not the first experience Mustafa pioneered: after his stint at Le Cordon Bleu in London in 2017, and work experience at restaurants in London and Antwerp after that, he returned to Pakistan for a break. Then the pandemic hit and, bored in Karachi, he converted the basement in his mother’s home into a kitchen and restaurant and invited friends and family for elaborate plated services. Word spread and he was summoned to politicians’ and celebrities’ homes to cook. ‘Gangsters, underworld dons, people who can’t just turn up to a restaurant – no, I can’t tell you who – would give me a call,’ he said. ‘The most wanted criminals. That’s who I was cooking for.’ And what do dons and criminals like to eat? ‘I make a mushroom rice and a garlic rice with mushroom stock – they love that sort of thing,’ Mustafa told me. ‘They’re actually very nice, simple people.’ For these meals, Mustafa charged up to Rs20,000 (£58) per head, often serving thirty or forty people for a party. His business boomed and, while he won’t disclose how much he made, he does show me photographs of two Italian mastiffs he imported to Pakistan. He was able to buy horses and start playing polo: a boyhood dream come true.

‘I miss being around people who like food,’ he said. ‘But I like money. You want fried rice? I don’t give a shit. I’ll make you fried rice.’

Mustafa wanted to replicate this privacy and exclusivity at Izakaya. ‘Imagine you’re at the fanciest restaurant in Karachi, enjoying some wine and cheese with your girl, and then you see the girl’s uncle,’ he said. ‘You gotta hide that bottle of wine! Or if you lied to someone about being sick so you couldn’t come to their party, but they see you out for dinner. Awkward! I thought there had to be a better way to have a night out.’ Members can bring their pets to Izakaya – one gentleman dines alone with his pet parrot – and there’s a dog walker and Filipina nanny available on request. Mustafa gets calls from mothers wanting to send daughters and their friends for a dinner – the girls want to dress however they wish without being ogled by strangers. ‘Izakaya is a “safe space”’, he said.

Thirty-eight years after the invite-only parties at Fujiyama, Izakaya has brought back something we crave more than the meal at a high-end restaurant: the ability to brag that we were there. Until recently, Izakaya’s Instagram did not feature photographs of the restaurant, and menu updates were shared only via Instagram stories, disappearing after twenty-four hours. Patrons often take photos in front of the restaurant’s distinctive duck-egg blue door – you’d recognise it if you’d been. ‘People want to show off,’ Mustafa shrugged. #IYKYK.

With all the talk of Norwegian salmon and nori imported from Dubai, it is easy to forget that Karachi is a coastal city. On a December morning last year, I joined thirteen people on the docks at Ibrahim Hyderi, a fishing harbour on the outskirts of Karachi, for the mahigeer boat tour through the mangroves (‘mahigeer’ means ‘fisherfolk’ in Urdu). The tour was led by Fatima Majeed, an activist and member of the community, and her father Abdul Majeed. While father and daughter told stories about the community and their history, others prepared a meal of fried fresh fish, prawn biryani and prawn karhai. The winter sun warmed our backs as the boat gently wound along Karachi’s coastal mangroves. Two men sat in a small space below deck, oil bubbling in a wok on a stove at their feet. They coaxed fillets of mushka (croaker fish) into the oil. Fatima tore warm roti into pieces, spooning chutneys onto them as she talked. ‘These mangroves, this water, they are the auliya and wali (protectors) for the people of Karachi,’ she said.

‘Members can bring their pets to Izakaya – one gentleman dines alone with his pet parrot – and there’s a dog walker and Filipina nanny available on request.’

Between 2010 and 2022, the WWF estimates that 200 hectares of mangroves in Karachi were lost to coastal land reclamation and commercial projects, leaving the city vulnerable to windstorms, cyclones and flooding. Fisherfolk have been protesting the deforestation for years, to little avail. Despite its potential impact on the city, the problem feels removed from the average Karachiite’s life, and this sense of disconnection spills over into how we eat; we ignore our coasts as worthy providers of the foods we consume. In Karachi, most people are hesitant to cook fish, which they have not grown up eating regularly. Crucially, good fish can be expensive, so the average household budget prioritises chicken or meat.

‘We do not eat like we are a coastal city,’ Asad Monga, a Karachi-based chef, told me when we spoke. ‘We don’t have a connection to our sea.’ Until 2022, Asad worked at buzzy new restaurants like Test Kitchen (sister cafe to Karachi’s fine-dining restaurant Okra). Then he quit his job and began to take trips with local fisherfolk, learning about the fish in Karachi’s waters (surmai, boi, tuna, ghissar, parrotfish, barracudas, squid and prawns). He would cook for them, using a fatty fish like snapper to make sashimi seasoned with lemon, salt and chillies. They loved it. This was the kind of cooking Asad had not been able to do in any of the kitchens he’d worked in – using entirely local ingredients from the city in which he was raised.

One day, Asad gathered seaweed and clams at Karachi’s most awaami (popular) beach, Clifton Beach. He dipped the seaweed in a batter of besan, salt, chilli, and sesame seeds and fried it up. He called these ‘seaweed pakoras’. Then he added the clams to mayo to make a dip, which he used to top the pakoras. He shared the dish on Instagram and took orders for two days, selling boxes for Rs700 (£2) each. It was such a hit that Asad made a higher-end version for a charity benefit at Izakaya (I laughed when he told me this: the patrons of Izakaya would never set foot on the trash-pocked sands of Clifton Beach). At Izakaya, the dish was modified to fit: the delicate wafer of a webbed pakora was topped with sashimi and served with prawn-head mayonnaise.

There have been other attempts in Karachi to encourage us to appreciate local ingredients. In 2021, siblings Anum and Mustafa Karim opened Fishop, a hole-in-the-wall restaurant on Karachi’s Boat Basin ‘food street’. Fishop sold fresh and marinated fish – like red snapper, lobster, eel, calamari, tuna and pomfret – alongside English-style bekti fish and chips, fish burgers, nuggets and sushi. The siblings were keen on giving the city something different: affordable, good-quality sushi (you could get tuna maki rolls for Rs 1000, or £2.50). ‘We’re so used to eating budget-friendly sushi abroad, and we wanted to have sushi that was accessible for everyone,’ Anum explained. ‘You don’t always have to dress up to eat it or spend a lot of money on it. Why should it be so expensive when the fish is from your own shores?’ Anum and Mustafa’s father Tariq Salim operates fishing trawlers, and they sourced their fish directly from the catch, choosing the ‘A-grade’ seafood that would otherwise be snapped up for export. They knew from their family business that only 10% of the trawlers’ catch ended up in the market or frozen food aisles of supermarkets. ‘We wanted to see if we could create an appetite for the best local seafood,’ Anum told me.

While other restaurants in the area served barbecued tikkas and kebabs, paratha rolls and broast chicken, the fourteen plastic tables outside Fishop filled up on weekends with people trying sushi for the first time. Fishop was a deliberate far cry from the air-conditioned environs of Fujiyama or Sakura. Often, people from the nearby Ismaili Jamat Khana would stop by on their way home and order platters of sushi to take away (the crispy California rolls accounted for almost 50% of all orders). By 2023, however, Fishop had closed. Between their day jobs and the demand for sushi, Anum and Mustafa were unable to give the restaurant the time it needed.

While these attempts to celebrate the local and seasonal find some curious customers, they have not been consistent enough to build a movement or change the ingredients found in most high-end restaurant kitchens in Karachi. Whereas sushi is prized for the freshness of its ingredients, the patrons who have the money to keep such businesses going like to know how far food has travelled to get to their plates: rice from Okinawa, tsukemono, wakame, and wasabi from Japan; nori and king crab from Dubai; and octopus, lobster, eel and yellowfin tuna available on demand from around the world. In Pakistan, the local is ordinary and, often, suspect. ‘We would rather pay for foreign ingredients than our own,’ Asad explained. ‘We assume our own Pakistani produce is third-rate.’

In 1986, the thrill of something new lured people through the doors of Avari Hotel – just as in 1948, when Karachiites were curious about the first water-front hotel in the city. But now, four decades after Fujiyama first opened, there is a generation of globalised mobile consumers in Pakistan for whom very little is truly new. Chefs like Asad Monga and Mustafa Sardar understand that to keep these Pakistanis’ interest piqued, you must present them with something novel in the most familiar settings. Seaweed from a local beach; a hole-in-the-wall restaurant serving up the freshest tuna sashimi in the city; a members-only restaurant with no sign, tucked away in a residential neighbourhood.

‘We do not eat like we are a coastal city,’ Asad Monga, a Karachi-based chef, told me when we spoke. ‘We don’t have a connection to our sea.’

In 2024, Fujiyama reopened after an extensive three-year renovation. The Avaris hope this revamp will draw curious people in. ‘We’re the new kid on the block now,’ Byram’s son Dinshaw Jr. told me. ‘Well, the old new kid.’ When I visited Byram in 2022, his three Labradors – Blondie, Barney and Buddy – ambled around the office and snoozed as he told me stories about his father. Byram remembered playing at his father’s feet with a trowel and pail as he surveyed the land and dreamed up a creek-side hotel. ‘All of this,’ Byram said, pointing out the windows to the palm-tree-lined hotel gardens, ‘all of this was barren land.’

Byram Avari passed away in 2023. His office at Beach Luxury Hotel has been left as it was, and his sons Xerxes and Dinshaw Jr., along with their children, continue to work in the smaller adjoining offices. Byram and Dinshaw Sr.’s edicts have been framed, and they now line the walls of the office. Who makes the rules? You and I, they read. Who amends the rules? You and I. They still guide the business today.

Credits

Sanam Maher is a journalist based in Karachi, Pakistan. She is the author of 'A Woman Like Her: The Short Life of Qandeel Baloch', named one of the best books of 2020 by The New Yorker and The New York Times.

Noorulain Ali is a photographer, currently based between Pakistan and the UK.

The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

This is the type of niche, super detailed reporting I live for. Incredible piece.

I finally made time to read the print issue of the the Vittles Magazine last weekend and this article blew me away. Such beautiful writing; I loved the stories, particularly the history of the Avari family whom I never knew anything about despite the hotel being the backdrop of so many stories I heard as a child. An incredible piece of journalism which was a joy to read. Thank you !