'You want to imagine what this tastes like? Fuck you, says AI'

Georgina Voss on how AI-generated images impact the way we look at photographs of food. Illustration by Ibrahim Rayintakath.

Good morning, and welcome to Vittles! Recently we announced Issue 2 of our print magazine on the theme of Bad Food which is selling quickly. The issue features more than 150 pages of all-new features, interviews, essays and restaurant content. You can read more about the contributors and content here. If you pre-order the magazine before 1 December, you will receive it for a discounted price, with an extra discount for paid subscribers. Pre-order now!

Today we have an essay by Georgina Voss about the proliferation of AI images of food and what this means for how food is documented – and our appetites.

The first image was in the window of a Subway on Bethnal Green Road: a high-res photo of two bread rolls overstuffed with meat and cheese, raisins studded through the dough, one roll cheerfully attempting to mount the other. The accompanying text identified the buns as ‘HOT CROSS CHEESY BACON BUN TOASTIES’. This was back in April. I was running late to meet friends, but the poster stopped me in my tracks. It had the energy of AI slop, but was in the actual window of an actual fast-food outlet. I took a photo. A week later, a second image presented itself in a McDonald’s in Southwark: a poster depicting a bright ocean of swirling cream, dotted with glossy green and white cuboids. The text described the dish as a ‘Minecraft McFlurry’. I took another photo and went on my way.

AI-generated images have their tells – strange light sources, repeating textures, disjointed gravities, an abiding aesthetic of the basic – but I found it impossible to determine if the pictures on these posters had been created with cameras or if they were computationally synthesised. The flat lighting and neat curves of the McFlurry had the weightless feel of something churned out by an AI engine; the raisins in the toastie could easily have been summoned with a text prompt. The longer I looked at the photos, the less sure I was about what I was looking at.

This uncertainty bothered me: I’d been hunting for AI-generated photos (so-called ‘synthetic images’) of food in the wild for several weeks. The internet is awash with fake snacks – pizza-flavoured KitKats; KitKat-topped pizzas – and I was curious about whether any of the swarms of digital images filling my phone existed away from a screen. AI-generated images are a patch of damp on the wall: annoying, spreading, and causing structural damage to the infrastructures through which they move. As ‘slop’, they are well-named, implying some gross weirdness, a viscous pool of stinking liquid seeping through social media. But I hadn’t banked on the stone-cold weirdness of seeing an image which had the hallmarks of synthetic generation selling something empirically real.

There are darker fears about AI images. If, and when, the technology becomes capable of creating truly photorealistic pictures, it will precipitate an epistemic breakdown of reality; unable to determine what is real and what is not, we will fail to know the world for what it is. To which a food photographer might say: Hold my McFlurry. While photography is commonly seen as a faithful depiction of the real, it has always been a nod and a wink to the relationship between representation and reality, and food photography delivers this uncertainty backwards and in high heels. This is a craft that transforms blobs of dense mineral oil into droplets of water on the surface of fruit, an industry in which photographers and stylists work their stagecraft to get the most captivating performance from a salad that desperately wants to wilt under the hot lights.

So, what happens if the food photographer and their arts are switched out for the chemical rush of the synthetic image? If it’s all illusion, then how does this shape how we look at food?

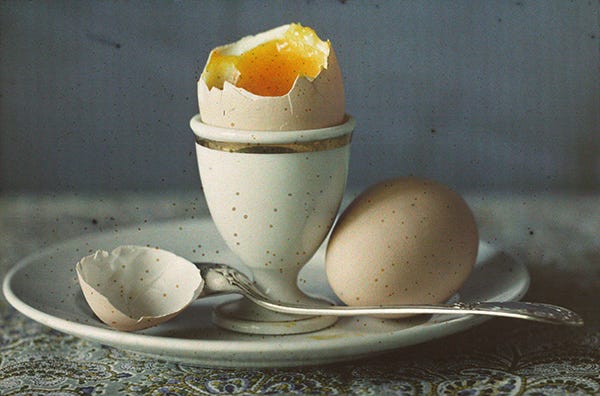

Consider two photos of eggs. The first is shot in 1910 by Wladimir Schohin, who used fragile autochrome techniques to create a delicately coloured photo of a soft-boiled egg, its yolk thickened into a deep amber. The second was created in 1940 by Nickolas Muray, using the three-colour carbro process to capture eggs cooked in peppers, the image brightly saturated, the yolks a lurid yellow. Is either of these photos more realistic than the other? What does an egg even look like, anyhow? Media scholar Rob Horning argues that things which look ‘real’ in photography are so because they meet our collective, cultural understanding of the way we expect those things to appear. An egg, therefore, looks like what everyone thinks it looks like.

From 1935, Nickolas Muray worked for McCall’s, the widely read American lifestyle magazine. His editorial photos show bountiful vibrant spreads – plump burgers topped with red circles of sauce next to pink radishes hasselbacked into stripy bumblebees. McCall’s’ large readership put the ‘mass’ into mass understanding of what food looked like in America. Muray’s images helped to shape a new visual language – bright, plentiful, dramatic, something which the viewer might want to lick.

Contemporary AI image technologies rely on these cultural forces that create collective belief. Their first principle is greed: a mass extraction, scraping and stealing of hundreds upon thousands of existing pictures. Text is attached to each image, describing what it shows (‘Egg’). Everything is poured into a computational Juicero, then squished. A machine learning model (MLM) then scans the description and numbers to feel out the relationships between the two – this is what an egg looks like? – and, eventually, statistically synthesises a new picture out of the data gloop using only a text prompt. But the synthetic image it produces can feel off, strange, like sand in the mouth. When I plug the prompt ‘Man eating cheeseburger’ into the DeepAI engine, it generates something unsettling. The burger exists in its own gravitational field and, though the cheese is molten and the man tightly grips the bun, the grease does not transfer to his fingers.

Yet even when strange, the cheeseburger is still knowable. When instructed to generate pictures of foodstuffs not widely represented in mainstream Western visual culture, however, the machine struggles: DeepAI translates ‘mapo tofu’ into thin tomato broth with carrot chunks, and ‘injera’ as dry cat food. Artists have addressed these biases; the collective Dimension Plus, for example, are working to enhance AI’s sensitivities about, and accuracy in representing, Taiwanese culture by feeding MLMs a curated mass of data about ti-hoeh-koé (blood cake). But beyond individual interventions, the main image generators continue to guzzle bricks of dominant culture and regurgitate them through their own didactic logics.

I’d initially assumed that if synthetic images of food existed off-screen, I would find them in places which sold MLM-knowable food: small cafes or burger joints with limited turnover, where it might be cheaper and easier to write a prompt than pay a photographer. But their presence continued to elude me. I started to feel foolish about my failed investigations: why would a cafe generate new AI pictures when a burger remains a burger? As summer approached, local eateries in South-East London stuck with their existing portfolio of stock images, sun-bleached photocopies and experimental Photoshop. These pictures weren’t always realistic – some appeared to have come out of a printer running low on cyan ink. But then again, as a customer, realism is not what I look for in photos of food. If I walked into a Subway and bought a Hot Cross Toastie, I know that my order would arrive smaller, flatter and sloppier than what’s on the poster, and still I would eat it.

The question was: when it came to really selling food, were AI images falling short?

The prime directive of commercial food photography is to make its subject appear tasty: as food photographer Patricia Niven tells me, ‘The magic is when it all comes together and you look at [the picture] and say, “Oh, that’s delicious!”’. Food marketer Melissa Cogo-Read is more direct about the aim of food photography: ‘It’s meant to make you feel really fucking hungry.’ There are some obvious visual tropes for producing a literal gut reaction – soft bread torn apart; obscenely juicy peaches. Working a shoot involves a collective of photographers, stylists, chefs and art directors who marshal their skills, coaxing food into the limelight.

Yet commercial food photography doesn’t necessarily allow for serendipity. In the UK, food advertising is tightly regulated, meaning that a shoot is defined as much by legal standards as creative vision – buns measured and meat weighed, the photography team working to a strict brief defined by an industry whose cultural power defines what food looks like and what looks like food.

On set, the creative team must commune directly with the food, bringing their understanding of both the appearance of a dish and how it behaves. Photographers and stylists know that, in reality, delicious food can look rough. Say you want to do a photoshoot for roast chicken. Chicken loses water as it roasts, becoming smaller, its skin shrivelling. To bring the feeling of hunger back and help maintain plumpness, stylists have been known to serve up a chicken half-cooked or even raw, its pink skin buffed to a glow with Marmite, soy sauce or (under lax regulatory standards) shoe polish.

Some foods are easier to manipulate than others. Easy enough to transform mashed potato into ice cream for camera, but far more difficult to beautifully photograph a simple egg, whose delicate, uneven shell makes it difficult to capture. Cooked, a runny yolk extends the challenge. ‘The food lives,’ art director Geneviève Larocque tells me; to shoot it ‘you have to be really fast but at the same time really slow. You’re waiting for the food – if you cut an egg and the yolk comes out, you have to shoot right away.’

If photographers are replaced by an MLM which has been instructed in the ways of the flesh, things go sideways. Plug in a prompt for ‘Delicious roast chicken’, and the system will retch up a raw, round bird, glistening in a pool of fake tan and digital schmaltz. AI hype-mongers treat the technology that produces this culinary kayfabe as a marvellous gain – a sack of spangles that, even if a little shaky, should be marvelled at (while simultaneously steering our eye away from that which the technology aims to replace).

As I looked at artificial pictures of roast chickens, I thought about David Cronenberg’s film The Fly – using physical special effects instead of CGI, it tells the story of scientist Seth, who, after a failed teleportation experiment, transforms horribly into an insect. Early in the film, Seth cooks a teleported steak for his lover, Victoria. After she spits it out, describing the flavour as ‘synthetic’, Seth realises:

The computer is giving us its interpretation of a steak. It’s translating it for us. It’s rethinking rather than reproducing it. And something’s getting lost in translation – the flesh … I haven’t taught the computer to be made crazy by the flesh, the poetry of the steak.

The MLMs which run through the computers that are here, now, don’t give a shit about the poetry of the steak, nor the work and skills that construct deliciousness: not the lighting experiments conducted by Cogo-Read’s team to encourage a tray of sugar-dusted croissants to bloom, nor the time food photographer Uyen Luu had to polish, by hand, five kilos of coffee beans after the client spotted one that was dull. Though AI image influencers boast of incantations of nostalgia warmth, editorial shadows and ultra-crisp texture to construct perfect pictures, the resulting images are flattened objects summoned from databases crammed with stolen photos. To me, the flavourless nature of synthetic images comes from the fact that, in order to make them anywhere near believable, one must discard that combination of skills and serendipity, telling the system loudly and slowly, ‘EGG. BROWN SHELL. SOFT YOLK. NOSTALGIC.’

Yet it is also true that in corporate photoshoots creativity is already subsumed, as artistic intent is whittled down and flattened by committee. The process that creates pictures in these settings is structurally closer to the way that AI images are generated. With this in mind, my confusion about the origins of the McFlurry and Hot Cross Toasty made more sense. None of the photographers I spoke to for this piece had used AI in client work, but everyone was aware of its lurking presence, and of the damage it could cause when clients begin to switch out art workers for proprietary software.

In her essay ‘The Photo Does Not Exist’, media scholar Avery Slater describes how a photograph of a shiny surface might contain a tiny reflection of the photographer. But a similar image made with generative AI also shows a reflection. ‘The generator has learned there will be something vague localised at the center of the shiny lenses,’ Slater writes, ‘but [in an AI image] that photographer is not opposite the subject. There is no subject: no one took its picture.’ When it comes to AI images, the system patches together an approximation of all those who came before, their craft and labour mulched down into a cold library of dead-eyed prompts, while offstage some poor sod with the job title ‘hunger engineer’ must now remind the machine that melted cheese causes stains.

Summer arrived and, finally, unhappily, AI images of food began to bloom in the wild, their tells lurid and unmistakeable. I regretted ever wishing for their presence. In a cafe in Mile End, a taped-up poster of biryani in which star anise morphs into a chicken leg. In a Brockley fast-food joint, a parade of glowing burgers, the jalapeño slices on the ‘Super Charger’ too evenly spaced on cheese triangles, making them look like an Elizabethan ruff. In neither venue did the workers know where the pictures had come from. ‘Printed off the internet?’ one member of staff offered cautiously.

Every image forces a reading, but reading images is slippery. Luu tells me how menus in Asia often have cut-out photos laminated onto them to showcase the dish. Luu’s mum and her friends ignore the aesthetic of the pictures – lighting, staging – and instead view them through their own experience as people who have prepared and eaten similar dishes. ‘It’s underdone’, they say when they look at the photographs on the menu. ‘It’s got too much pepper.’ AI photos sever this relationship. They say ‘Fuck you’ to what the body knows, what it may have learned over time. ‘You want to imagine what this tastes like? Fuck you’, says AI.

In reality, there is no perfect photo of food. The thread that links professional food photographers’ craft and the fantastically deranged photos of roast dinners outside my local caff – where different stock images of plates, condiments and sliced beef are all frankensteined together onto laminate – is that the creators of each are somewhat free of a system which places technical limits how an image can be made. Maybe, off-screen, AI food pictures can be humbled when they are forced to exist within the physical infrastructure of hospitality: faded paper, sauce splashes, even sitting alongside actual photos of actual food. Synthetic images are dangerous when they become the stock image, setting the terms for what a good photo of food looks like – an immaculate image of a hovering burger, forever fixed in aspic.

Down in Greenwich, a Nepalese food stall has a picture of a family gathered around a table of momos, the dumplings impossibly neatly stacked, everyone smiling with the shark grin of the machine. ‘My manager made it,’ the server tells me with a slight eye-roll. What do customers think? ‘The children love it,’ he says, ‘they come and point: “Ay ay ay! ChatGPT ChatGPT!”’

Credits

Georgina Voss is a writer and artist, whose work explores the presence and politics of large-scale technology and heavy industry. She is author of Systems Ultra: Making Sense of Technology in a Complex World (Verso). Her work has been exhibited and performed at institutions including transmediale, STUK, TAC Eindhoven, Deutsches Technikmuseum Berlin, and the Design Museum. Georgina was co-founder and director of the creative studios Strange Telemetry and Supra System Studios. She lives in London with a handsome cat.

Ibrahim Rayintakath is an illustrator and art director based in his coastal hometown of Ponnani, India. His editorial work, which explores themes of culture, politics and mental health, has appeared in various outlets like the New Yorker, the New York Times and nbc.

The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

This all reminds me of Baudrillard, talking about the difference between Simulation and Representation.

AI slop does not attempt to represent the food you will receive. It is a pure Simulation. It’s verisimilitude is irrelevant. Much like the AI Minecraft McFlurry - the fact that the ice cream bears no relation to the picture is almost the point - we are meant to care about the concepts and the conflation of them. But only at a surface level. The picture is to the McFlurry what the McFlurry is to “real” food.

I read and share this seasonal article about Baudrillard and Pumpkin Spice annually as we plough through the information crisis that is the enshittoscene

http://www.critical-theory.com/understanding-jean-baudrillard-with-pumpkin-spice-lattes/

It’s relevant here.

An incredible essay-- thank you!!! Also the DeepAI cheeseburger image is really selling the idea of just eating an extra piece of cheese on top of your cheeseburger. Think the algo is on to something.