15 Cookbooks That Changed Everything

The most influential British cookbooks of the last 75 years; for better, or for worse, by Ruby Tandoh.

This essay is part of our supplement Too Many Cookbooks and is best read on our website here. To read the rest of the series, please click below:

Reinventing the Hexagon, by Jonathan Meades

Machiavelli in the Kitchen, by Rosa Lyster

‘There is no recipe, take it or leave it’, by Yemisí Aríbisálà

Cookbooks in Translation, by Guan Chua, Christie Dietz, Anissa Helou, Ibrahim Hirsi, Saba Imtiaz, TW Lim, Lutivini Majanja, Meher Mirza, Marie Mitchell & Rachel Roddy.

It is 75 years this year since Elizabeth David’s A Book of Mediterranean Food was published. It was her first book, and the one that, if Food People are to be believed, set in motion a complete change of attitude in British food. It has been credited – sometimes dubiously – with introducing us to the idea of the Mediterranean, to boeuf en daube, and to olive oil. But whether or not any of these claims hold up, the most important thing Mediterranean Food undoubtedly did introduce us to was the idea that a cookbook was capable not just of bringing in new flavours, but also of bringing about a genuine change of taste.

In the decades since, Britain’s food has transformed. ‘Let’s face it,’ future Food Programme broadcaster Derek Cooper wrote in 1967, ‘food is not something you talk about.’ Today, we are more omnivorous, we know more about ingredients and cuisines, we do talk about food – sometimes to the point where I wonder if we might even have gone too far. Food writing, and specifically cookbooks, have been integral to this change. In the 1960s, journalists noted with alarm that 100 new cookbooks were being published in the UK every year. Now the figure can run into the thousands. Most genuinely aspire to change our food lives for the better – but it turns out that we almost never agree on what ‘better’ means.

For the last few years, I’ve been working on a book about modern food culture, in which I’ve had to dig into what ‘influence’ really is, and where it comes from: the contorting forces of tech, new media pathways, supermarkets, migrations, marketing and industry. We talk a lot about influence, but we seldom clarify what, or whom, that influence acts on. Last year, T: the New York Times Style Magazine published a list of ‘The 25 Most Influential [American] Cookbooks From the Last 100 Years’. I love all the books on that list – from Edna Lewis’s The Taste of Country Cooking to Molly Katzen’s Moosewood Cookbook – which is how I knew something was up. Afterwards, the writer and historian Jessica Carbone pointed out that: ‘For the Times list, an “influential” cookbook offers narrative, rather than culinary, innovation.’ What this really means is that these are the cookbooks that changed cookbooks, which are not always – or even often – the cookbooks that changed cooking.

The reality is that it is difficult for cookbooks, by themselves, to transform the way we eat. But at the right time, with the right backup, deployed at the right pivot point in the culture, they can change things. This list is about 15 books that have played a part in reinventing food culture in Britain – by means noble or nefarious, for better or for worse.

1. Great Dishes of the World, by Robert Carrier (1963)

The book that invented the luxury cookbook as status symbol

Eleven million copies. That’s how many Great Dishes of the World is supposed to have sold, although this is so obviously not true that I can only assume the numbers came from Carrier himself – a lifelong PR man who described himself as ‘the most successful media cook in the world’. Here’s what we do know: it contained more than 500 recipes, weighed over 2kg, and cost 85 shillings, which is the equivalent of almost £100 today. The recipes ranged from lobster à l’Américaine to duck à l’orange and choucroute garnie. If Carrier had sketched out the ‘world’ he was talking about, it would have looked like a medieval mappa mundi, except with Provence, not Jerusalem, at the centre.

And yet the 11 million myth does capture something about the outsized influence of Robert Carrier. There are famous chefs, and there are celebrity chefs. Carrier was the latter – a larger-than-life figure who got around by helicopter. After the success of the book, he opened a restaurant and became a TV star. But this first book is where his essence is most concentrated. Within the first few sentences, he references the Medicis, the collapse of the Roman empire and the Crusades, then moves swiftly on to foie gras in brioche. ‘Culture,’ he wrote, ‘stems from the stomach as well as the brain.’

Huge, wildly expensive status cookbooks – like some of those published by Phaidon today – were almost unheard-of before Carrier, and the ones that did exist definitely weren’t mass-market. Great Dishes of the World moved the dial. But the magic of this book is that, for all the camp, at its core it remains a highly usable collection of recipes. You’re not supposed to fantasise about the bombe au chocolat, you’re supposed to make it, and Carrier gives concise but robust instructions for doing so. You could travel the whole world from your kitchen, he insisted. Or at least, the world according to Carrier – and maybe that’s just the same thing.

2. Pressure Cookery, by Marguerite Patten (1977)

The book that changed our relationship to new kitchen technology

With more than 150 cookbooks published, and cumulatively tens of millions of copies sold, Marguerite Patten is perhaps the most prolific – and useful – British cookery author of the last century. She worked as a home economist for fridge and electricity companies, and was a radio broadcaster during the second world war, sharing practical recipes for a nation on rationing. By the time she started writing cookbooks in the 1950s, she had the approach down pat: she was a demonstrator, saying only as much as was needed to communicate the basics of a recipe. If her books tell a story, it isn’t through their words.

Patten’s best-known book is Cookery in Colour from 1960 – a chromatically overcomplicated book with lurid photos and rainbow pages. It spoke to the realities of the time, even covering TV dinners, and within five years it had sold 800,000 copies. You could make a case that it made inexpensive colour cookbooks the new normal. But where Patten really flexed was in her crossover work with kitchen goods: recipe pamphlets for kitchen scissors and Turmix food processors, becoming an honoured member of the Microwave Association. What better way to influence how people cook than to change the equipment they do it with?

Patten had always been a pressure-cooker advocate, but Pressure Cookery, which somehow managed to make these machines relevant to everything from taramasalata to beef olives, was a turning point. It kickstarted a late-70s pressure-cooker movement that you could compare to the air-fryer boom today – brands got involved, money was injected, more cookbooks were made, more cookers were sold. It joins the many gadget and appliance cookbooks that have transformed perhaps not what we eat, but how we cook it: from Mary Berry’s Aga books to my grandmother’s cottage pie recipe from a late-1950s Belling electric oven cookbook – a book that is slimmer than a Screwfix catalogue and has about as much charisma. This is where the power is, for better or worse: air-fryer cookbooks accounted for more than half of the top 10 best-selling cookbooks last year.

3. A Sainsbury Cookbook: Cooking with Herbs and Spices, by Josceline Dimbleby (1979)

The book that changed the diversity of supermarket ranges

Food writers have long been troubled by a loveless truth: the reason people eat what they eat is, more often than not, because that’s what the supermarkets sell. You can write against this, or you can use it to your advantage. There have been many supermarket cookbooks. In the days before supermarket recipe magazines, you could buy these in-store at the same time you decided which ingredients to pick up a few aisles away.

Cooking with Herbs and Spices was one of the earliest, and the most ambitious. Josceline Dimbleby talked about the root-to-stamen school of medieval flavourings, how the Victorians fumbled basic seasoning, and the mission to bring spices back. She wrote recipes for lamb’s liver with paprika and cumin, spiced eggs with cucumber and Marrakech meatballs. ‘They were a little worried,’ she explained later. ‘This was 1979, and then they still only stocked little drums of mixed spice, mixed herbs, and thyme.’ But the book did so well that Sainsbury’s expanded their range. The books inserted themselves into real-world systems of supply. As food historian Polly Russell put it to me recently, supermarkets went from selling products to selling taste.

Over the next 15 years, Sainsbury’s commissioned a couple of dozen cookbooks, covering everything from Chinese cookery and regional French cuisine to cooking for one. The authors included Jane Grigson and Ken Hom. The spice range continued to grow, and packets of wok-ready noodles rose through the shelf hierarchies to eye level. These books are just one part of the negotiation between retail and writers: Delia’s red button through to Sainsbury’s HQ; Jamie Oliver’s supermarket ads; Claudia Roden consulting for supermarkets; Rosamund Grant advising brands. The recipe dreamers and the retail tacticians – the heart and the head.

After the paywall: Jamie, Delia, the books that changed our relationship to Chinese food, to chefs, to British produce; books that changed how we talk about food, how we feel about food, and more.

4. Delia Smith’s Complete Cookery Course, by Delia Smith (1982)

The book that raised the base level of British cooking skills

The success of Delia’s Complete Cookery Course is that it gave neophobic British cooks the things that they liked, all in one place, and with absolutely no room for misinterpretation. When you make the English salad sauce, you boil the eggs for ‘exactly nine minutes’. You simmer gently. You cover and uncover pans when Delia says so. Ingredients are calibrated down to the quarter-teaspoon. Delia speaks to risk-avoidant British cooks on a soul level. We avoid surprises at all costs, even if they might be good ones. And so a cookbook of reliable recipes will fare better, among home cooks here, than one of potentially – but not provably – delightful ones. Luckily for us, Delia manages to be both. The only books that have spent more weeks in the bestseller charts in the last 50 years are Men Are From Mars, Women Are from Venus and A Brief History of Time. The cosmos, the unfathomable science of heterosexual gender relations, and then Delia – here to remind you that a soft boiled egg takes a minute at a simmer, then another six minutes off the heat.

5. Ken Hom’s Chinese Cookery, by Ken Hom (1984)

The book that changed our relationship to Chinese food, and to food TV

Ken Hom wasn’t the first cook on the BBC, but he was the first cook the BBC truly made. Delia had newspaper columns before she went on television, Madhur Jaffrey was an actor, Mary Berry wrote for Hamlyn, but Hom was an American who, until Chinese Cookery was filmed, was totally unknown. The television preceded everything – including, or especially, the book. There was the world-building TV show, through which you got the feeling of Chinese cuisine – touring a Hong Kong fishing village, eating in a dim sum restaurant – and then the cookbook, which unpacked how to recreate this stuff at home. ‘[TV] is a medium of emotion and general impression, but not a medium of detail,’ as TV exec and Ready Steady Cook mogul Peter Bazalgette put it, and so ‘the programmes axiomatically give rise to the need for recipes’.

And the recipes are great – this is what sets Hom’s book apart, and pulls the Ken Hom media empire’s centre of gravity a little back towards the written word. He discusses the regional dishes of China and gets into the morphological differences between woks. Northern-style stewed beef and kidney and beancurd soup run alongside the Cantonese dishes that British people would have been more familiar with. It’s a thorough cookbook, ambitious and unpatronising. It kickstarted a 15-year period of Ken Hom domination; by 2001, it had sold well over 500,000 copies.

There had been earlier advocates for Chinese cooking, not least Kenneth Lo, whose books and cooking school popularised Chinese food among the 1970s and 80s foodie class. But Hom went further, through TV shows and books, through personal appearances, through a mail-order Chinese ingredient kit and Ken Hom-branded steamers. When he put his own name to a wok, it came with a 64-page booklet and a cassette tape. The secret of his influence was to create an entire extended culinary universe: all interconnected, all purchasable.

6. The Observer Guide to British Cookery, by Jane Grigson (1984)

The book that changed our perception of British produce

When people talk about Jane Grigson’s greatest work, they might tell you about the Fruit Book, which lovingly addresses everything from how to deal with quince skin to Louis XIV’s pineapples. Others choose Good Things, a collection of food love letters to strawberries, asparagus, rabbit, chicory and more. I was on a train once reading Food with the Famous (an esoteric collection of literary recipes, with sources from Austen to Zola – it is Grigson’s own favourite work) – and somebody interrupted to say that his butcher used to quote him passages from English Food, the 1974 masterwork in which Grigson mined old cookbooks for precious, and near-forgotten, traditional recipes.

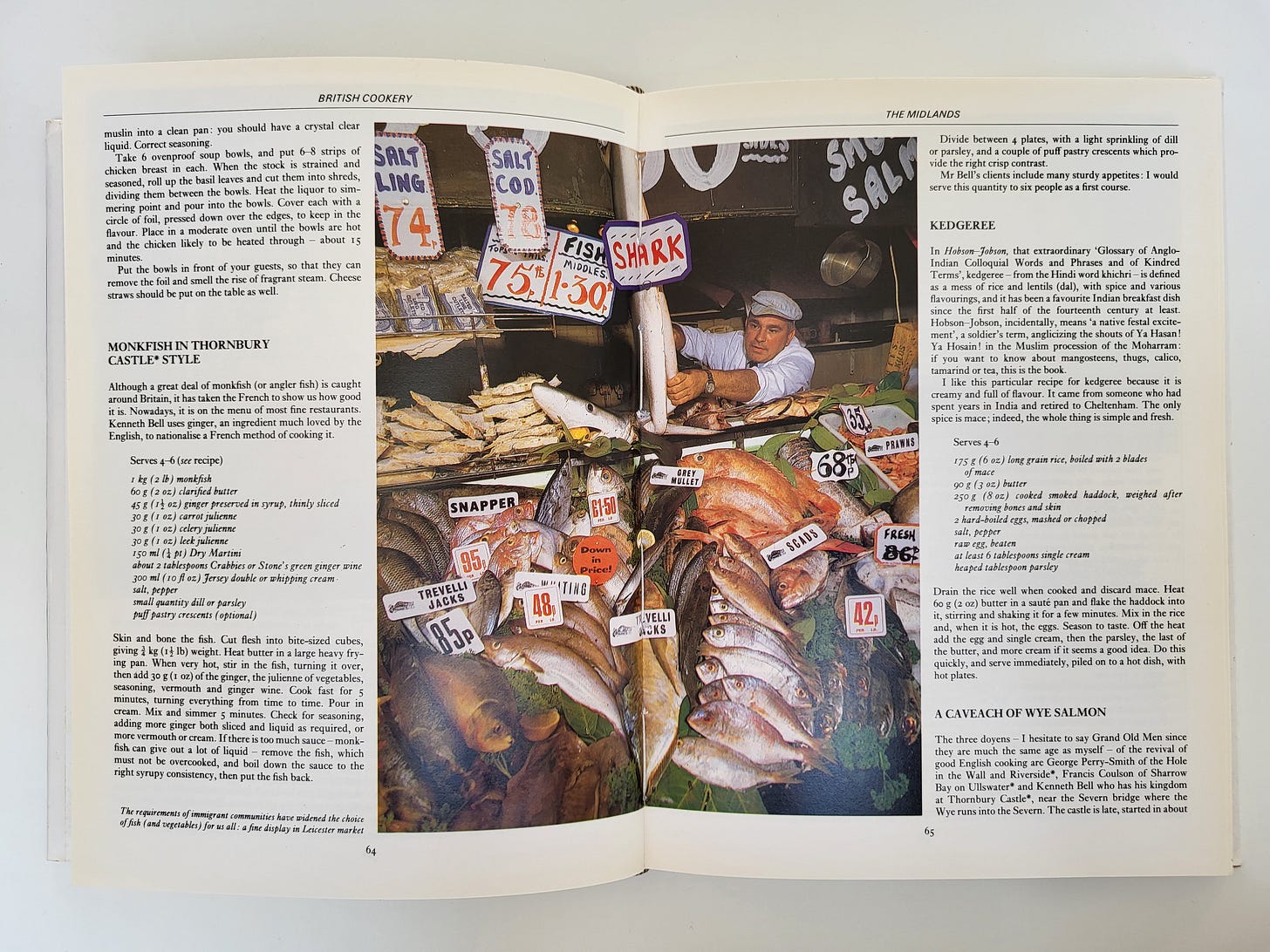

What people tend not to bring up is The Observer Guide to British Cookery, a clunky, exhilaratingly outdated tie-in to an Observer series that Grigson wrote in the early 80s. And yet this is her greatest book. She begins in the south-west, writing about medieval fish weirs and mud horses and Tamworth pigs. There is West Country mustard. There are the improbably steep lanes that twist through the Lyth valley until you reach a farmhouse where local lamb is served with damsons. She writes about the herring fishermen of Loch Fyne, and speldings cured on the pebbles of the beaches of the Moray Firth. She writes about the people and places where these foods are grown and made. If English Food is the theory, then British Cookery was the praxis. It provided practical answers to a follow-up question: once you know what our indigenous cuisine is, how do you keep it alive? ‘I used to think, when I started writing about food 20 years ago, that salvation lay in improved cookery,’ Grigson wrote in the book’s introduction. ‘Now I conclude that salvation lies in shopping.’

Grigson joined a wave of foodies (the term was hard-launched in the UK that same year) trying to fix the problem – as they saw it – of industrialised food. Patrick Rance’s Great British Cheese Book, the book that revived traditional cheesemaking, was published in 1982. A real food counterculture was rising. And then, in perhaps the most intense year of food cultural discourse in living memory, Grigson’s Observer guide came out. You can see its influence in the Good Food Directory by Drew Smith and David Mabey in 1986, and in a landmark Telegraph series a couple of years later. Henrietta Green, often credited with resurrecting the farmers’ market scene, dedicated her Food Lovers’ Guide to Britain to Grigson. ‘The Observer Guide to British Cookery is seminal,’ food writer Jenny Linford told me. She recently referenced it herself, in her upcoming Great British Food Tour.

In 1985, Elizabeth David called the guide Grigson’s ‘latest and to date bravest book’. It would also be her last. She died in 1990, and although she’d been tweaking English Food in her final years, the Observer guide was already long out of print. More than any of Grigson’s other books, this is a book about people. It isn’t a timeless book – this is why it could make a difference, because it spoke to the moment. Food writers often get lost in words, referencing books that reference other books, accidentally creating a food-writing ouroboros that has almost nothing to do with life. The Observer guide breaks the cycle. Nettle soup, mutton pies, ackee and saltfish, apple amber, brandy angel cream mousse – and the people who make them come true.

7. Caribbean and African Cookery, by Rosamund Grant (1988)

The book that changed the way we talk about diasporic food

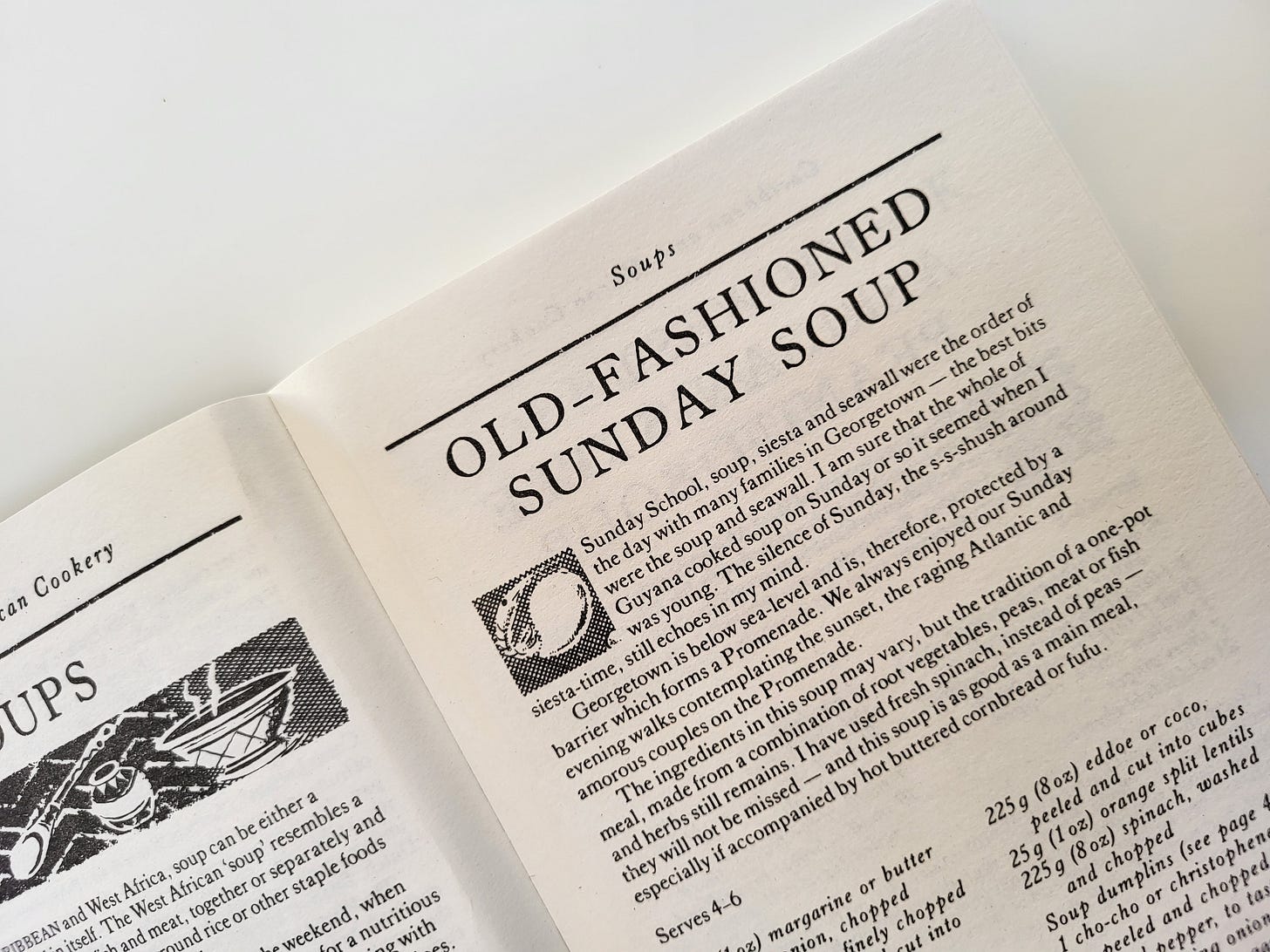

‘I am sure that the whole of Guyana cooked soup on Sunday, or so it seemed when I was young,’ Grant begins in Caribbean and African Cookery. ‘The silence of Sunday, the s-s-shush around siesta time, still echoes in my mind.’ Born in Guyana, Grant had been fine-tuning her recipes for years, through a catering business and a co-operative restaurant in north London called Bambaya. Having run cooking classes, a cookbook was a natural next step. ‘I didn’t finish my teacher training’, she told me, ‘but I wanted to teach.’ And so she wrote.

Grant wends her way from a prawn palava, inspired by her travels in Ghana, to Senegalese yassa and ital rundown. She recites the ‘colourful names’ of Guyanese fish: banga mary, flounder, queriman, ice fish, yarrow, snook. She gives a summary of all the advice she has ever been given to tamper the intense bitterness of corilla. ‘The end result has always been the same,’ she notes. ‘It remains bitter.’ Barely a recipe goes by without Grant explaining who and where it came from. It’s a rare cookbook author who cites their influences, but Grant fills the pages with secondary characters, from a cousin in New Orleans to siblings, friends and Prince. Maya Angelou wrote the foreword. She spoke about the myth of a classic cuisine, self-contained and virginal: ‘Happily Rosamund Grant’s new cookbook makes no such unappetising claims.’

Caribbean and African Cookery was the first cookbook published in the UK not just to talk about Caribbean or African cookery, but to tell a rich and nuanced story through it. At the time the book came out, the UK’s pre-eminent author of Caribbean cookbooks was Elisabeth Lambert Ortiz, a glamorous writer who was, all the same, from Harrow-on-the-Hill. Even the more insightful books took a narrow view, seeing modular islands and not an archipelago. Grant wanted to reconsider things, connecting the food of the islands and of Guyana outwards, along the lines of influence created by the Transatlantic slave trade, commerce and migration. ‘It’s not about the countries,’ she explained to me, ‘it’s about their harmony and connections with Africa.’ Writers follow her lead even now – sometimes knowingly, at other times just moving happily through the furrow that Grant ploughed nearly 40 years ago. You see it in a detail of a recipe, or in a particularly thoughtful treatment of these interconnected food histories. It’s a small proof that you can, as a Black author, write a cookbook your way. ‘To give a sense of oneself to a dish,’ she wrote, ‘is as important, to me, as getting it right.’

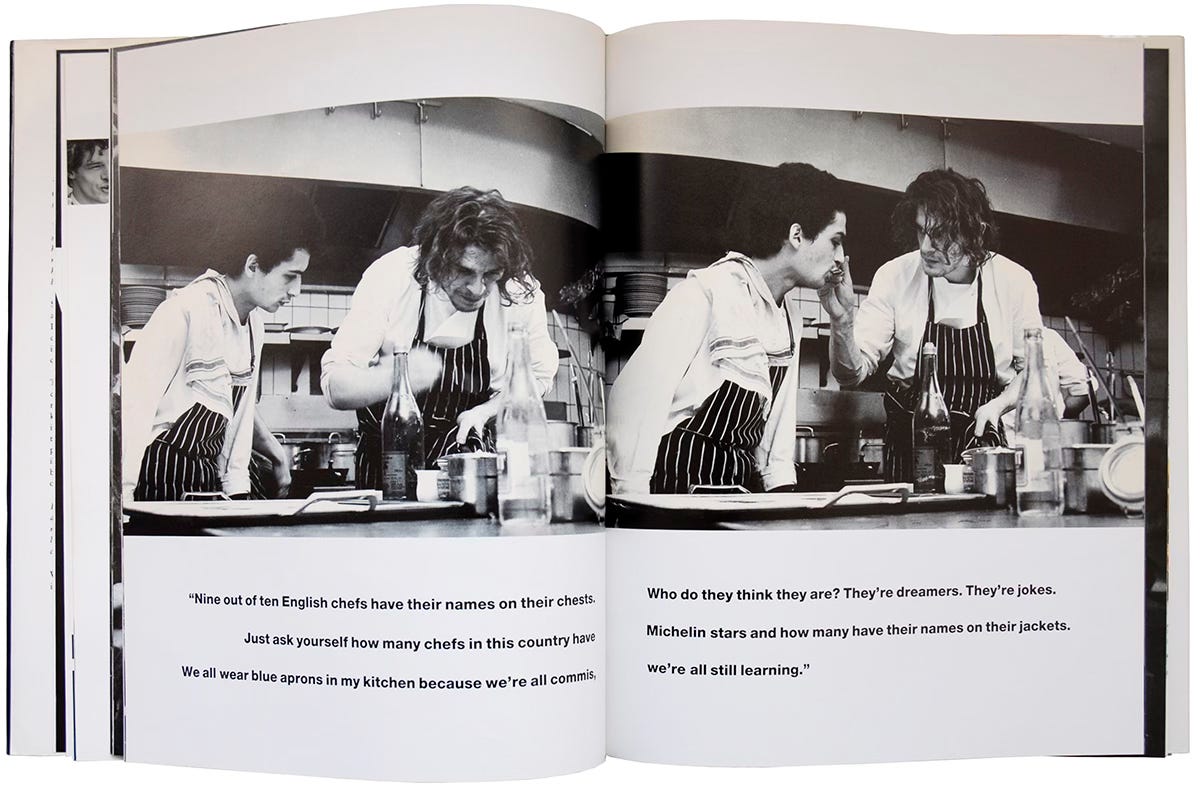

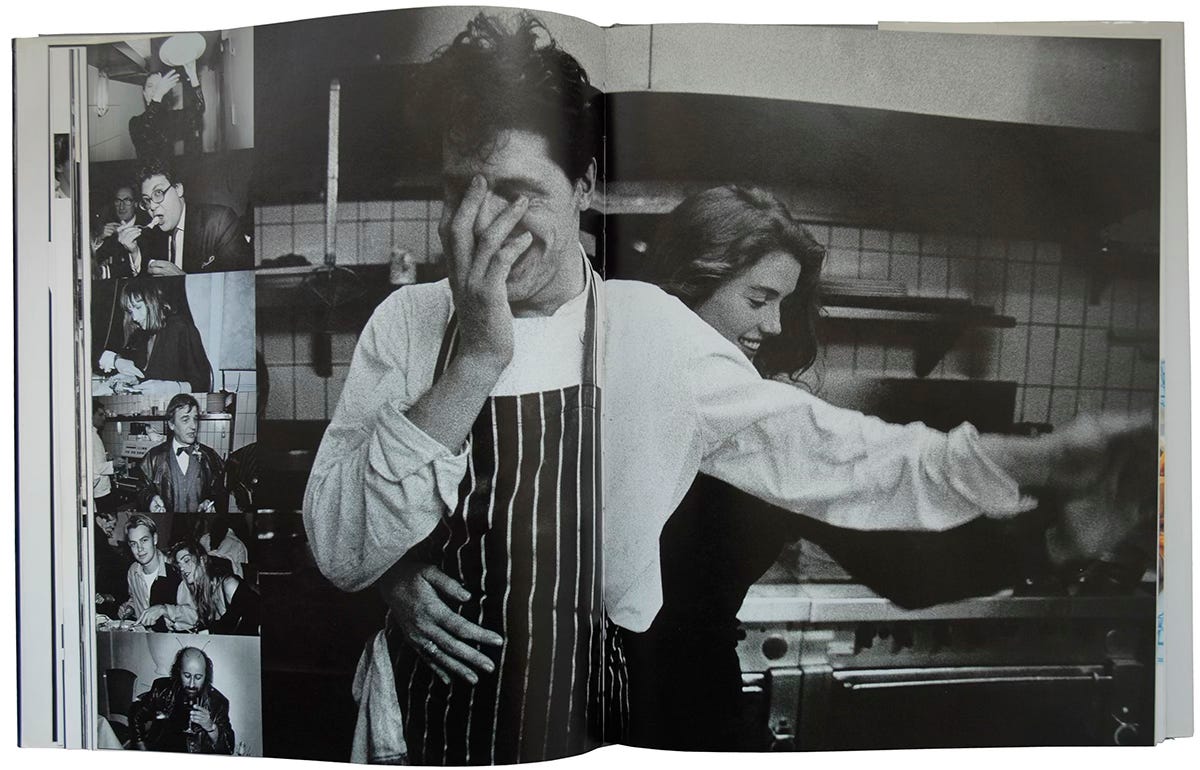

8. White Heat, by Marco Pierre White, photography by Bob Carlos Clarke and Michael Boys (1990)

The book that started the cult of the chef

Nobody remembers White Heat for the mango tarts – nine mangos, cut into 3mm slices and arranged on puff pastry discs like the petals of a marigold. Nobody remembers it for Michael Boys’ hazy photo of the hot foie gras with lentilles du pays and sherry vinegar sauce, bathed in what looks like the light of a setting sun. Nobody remembers it for any of the extravagantly impractical recipes, for that matter, or the earnest and occasionally touching recipe descriptions. People remember White Heat for a run of just 35 pages towards the front of the book, all in black and white, in which the photographer Bob Carlos Clarke captured Marco in blurred, seething motion – brooding, tasting, flambéeing and smoking cigarettes. This makes White Heat the cookbook equivalent of Mary Poppins – a film that everybody remembers for one or two memorable songs, but which is, in fact, about banking.

It’s hard to think of a book so discussed and revered, and so little cooked from. But it did what it needed to do, which was to reinvent the character of the chef and, in doing so, create a swell of chef discourse that would lead to outcomes both fair and foul: Anthony Bourdain, primetime Gordon Ramsay, Lucky Peach, The Bear. ‘There was life pre-Marco, and post-Marco,’ as Bourdain wrote on the 25th anniversary of the book. ‘White Heat brimmed with casual admissions of what we all knew as chefs: that it was a hard, brutal, repetitive business… This book gave us power. It all started here.’

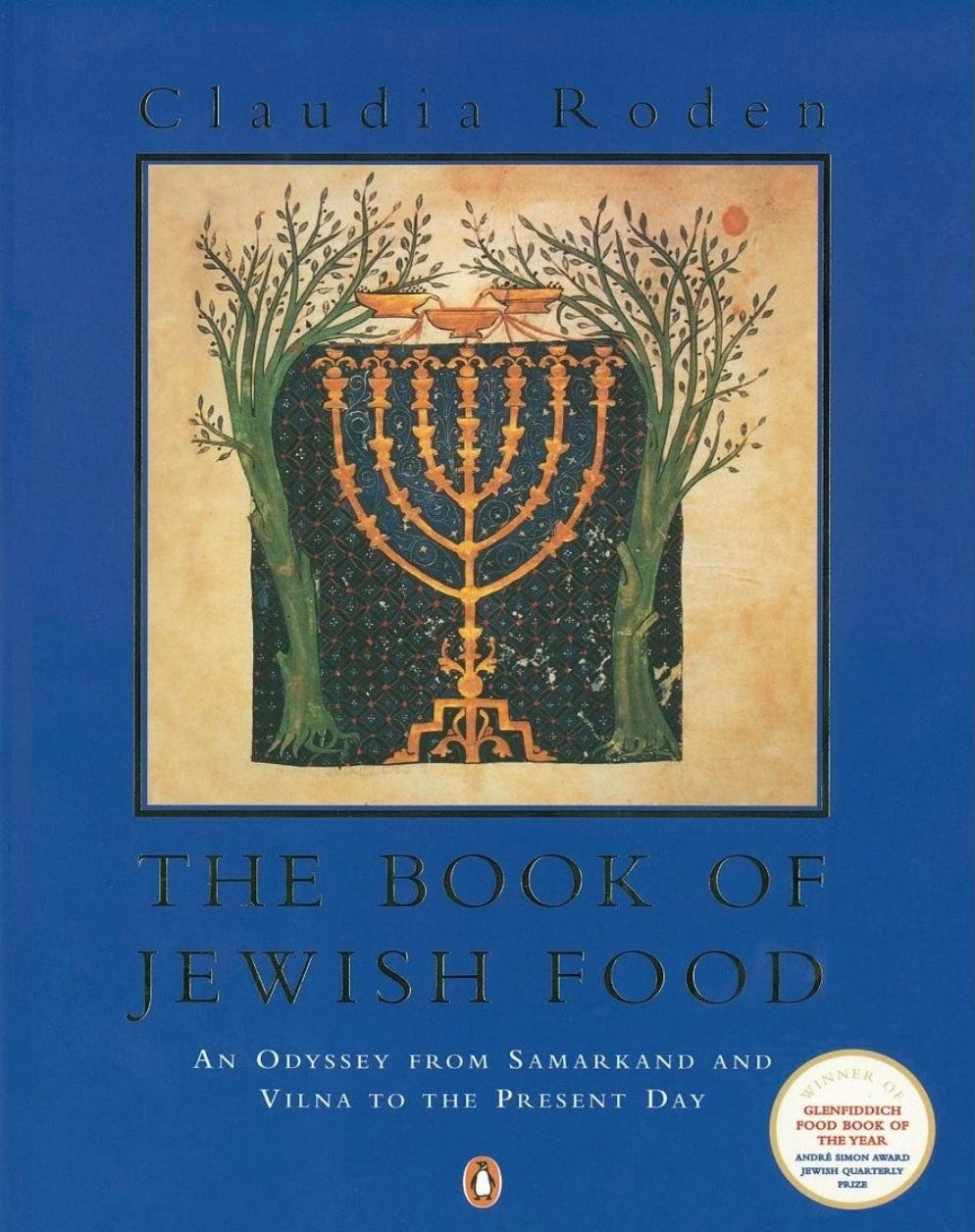

9. The Book of Jewish Food, by Claudia Roden (1996)

The book that changed everything we think we know about Jewish food

Some recipes create instant shockwaves – the sheet-pan drop cookie technique, the viral tomato feta pasta – and are forgotten just as quick. The Book of Jewish Food is different. Over the last three decades, it has diffused slowly through the culture, and it is now the ur-text for all subsequent work on Jewishness and food – not just a book of Jewish food, but the book. Read anything about Jewish cooking, go into a non-geographically specific deli or open a magazine about food culture and you’ll feel the influence of Roden’s masterwork. Its stories are retold by countless food writers. Its references and recipes are rehashed. Roden has got to be one of the most cited – and plagiarised – food writers of the past half-century.

The book’s secret strength, I think, is that it started with a question: is there Jewish food, really? Or are there only Jewish cooks? For 15 years, Roden wrote her way towards an answer, and in doing so became the first writer to meaningfully connect pumpkin flan from Veneto, walnut and orange passover cake from Istanbul, a Baghdadi Passover dish of meatballs with garlic and minty sweet and sour sauce, Syrian kibbeh, Hungarian walnut and poppyseed kugel. ‘Every cuisine tells a story,’ Roden wrote. ‘Jewish food tells the story of an uprooted, migrating people and their vanished worlds.’ You could say Jewish food – as a coherent concept, as a totality, treating Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jewish food with equal care – was not reflected in cookbooks until Claudia Roden wrote it into life.

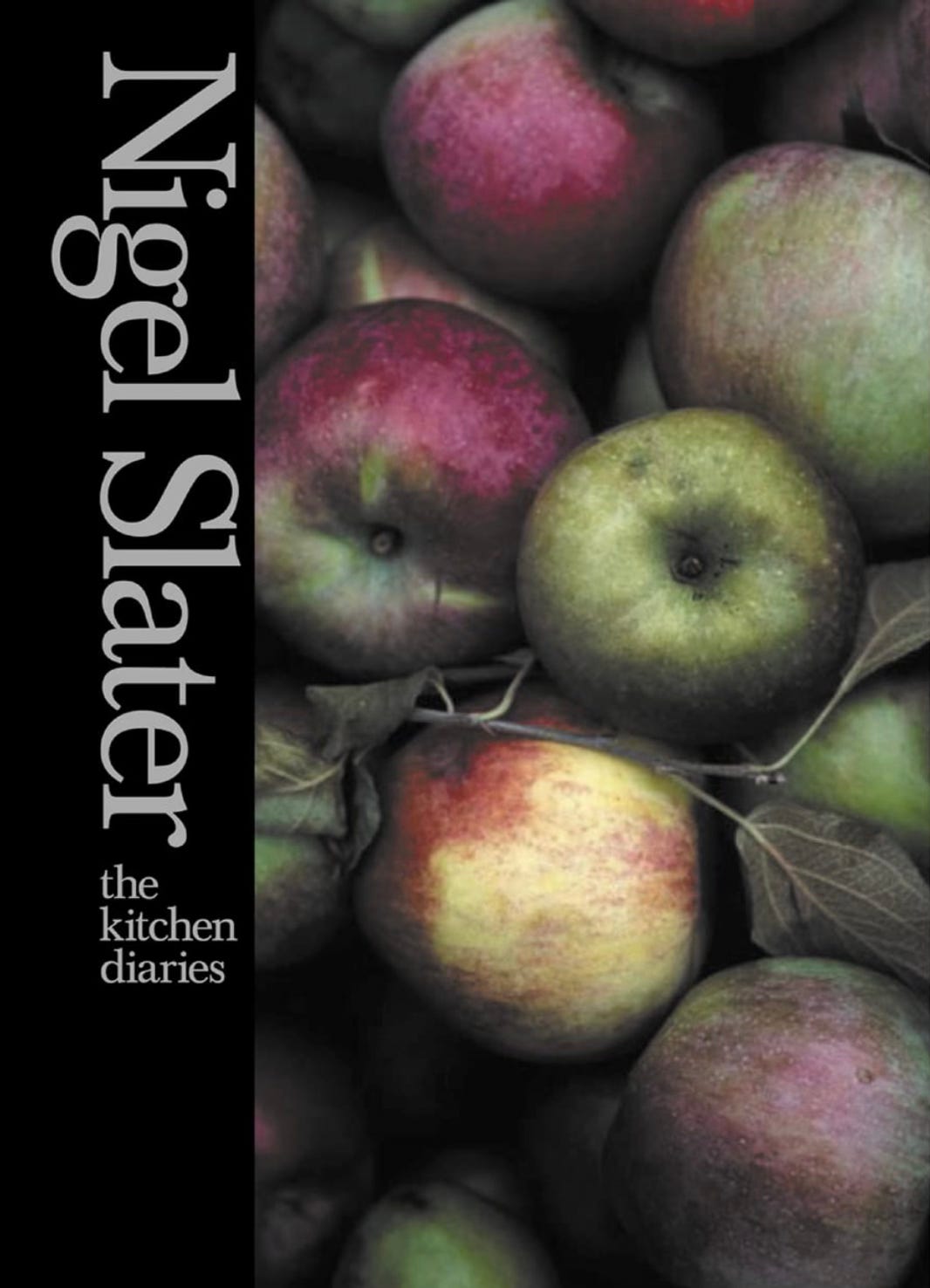

10. The Kitchen Diaries, by Nigel Slater, photography by Jonathan Lovekin (2005)

The book that changed how we feel about food

No book captures Nigel Slater’s essence as a writer like The Kitchen Diaries. It’s in the cadence of the words, and the quietness, his unique ability to turn a digression into a plot, the way the recipes cling to the prose like tubers to a root – this is what people love about him. And this book, closer in form to The Pillow Book than The Joy of Cooking, is one of his best. Loganberries, ‘rare pink currants’, cats sprawling on hot flagstones, amber fat, custard-coloured mangoes, ‘the smell of white rice cooking, clean, nutty and warm’.

Lots of writers can describe flavours or historicise their ingredients, but this is more intimate. Slater sees things only through the loving distortions of his own appetite. The personal approach isn’t even memoir, but a love for the pleasures of the moment, right here, right now. We take this style for granted these days, as though food writing was always going to be sensual, even delicately horny, and highly personal. But I can’t stress enough just how much of a tonal shift this has been. It’s no longer a style of food writing, to dwell on the tactile joys – it’s the default.

By the time he wrote The Kitchen Diaries, Slater was already 20 years into a food media career that had started with food styling. (He claims to have invented the term ‘food stylist’ – an unverifiable claim that I nevertheless respect.) He has been a writer-director-producer since the start, and visuals are as important as the words. In the introduction to his very first book, the Marie Claire Cookbook, he made a point of ‘the decision to abandon props, those traditional scene-setters’. Burnt bits should be captured, filo rumpled like the sheets of unmade bed, juices allowed to pool. ‘In the world of food photography,’ a 1987 article observed, ‘Nigel has the same impact as the first painter who used perspective.’

Since the late 1990s, Jonathan Lovekin has been the photographer for both the books and Slater’s Observer columns: textures of ceramic and light, taken in Slater’s own kitchen. ‘We want it to feel like it was somewhere,’ Lovekin told me – to find the frame, rather than engineering it in a studio. Incidentally, Lovekin has also been the photographer for many of the Ottolenghi books, which makes him one of the most influential figures in publishing in his own right. ‘There are a lot of [publishing] meetings that people I know go into, and they bring out one of these books, maybe The Kitchen Diaries, and they say – this is what we want,’ he told me.

None of this would have been possible without Louise Haines (Slater’s editor), or the publisher 4th Estate, by whom the first few of these huge, storytelling books were produced – at a time when the drive was towards TV tie-ins. Some cookbook authors change how people cook. Others change how people write. A tiny minority change how people feel about food – this is the difficult one. Nigel Slater is one of the only people I can think of who has done all three.

11. Mary Berry’s Baking Bible, by Mary Berry (2009)

The book that changed who gets to write a cookbook

There is nothing particularly interesting about the recipes in Mary Berry’s Baking Bible, and yet, in a roundabout way, this book has had a greater impact on British baking than the previous 50 years of cooking literature combined. More than Elizabeth David’s Talmudic English Bread and Yeast Cookery, or Andrew Whiteley’s cult favourite Bread Matters. That’s because Baking Bible was published the year before the first season of the Great British Bake Off aired on the BBC: it set the tone for the show, it cast the judge, it provided some of the recipes. It was the first unofficial Bake Off book.

Bake Off has been to the publishing industry what a long, hot summer is to Wall’s. Each series presents 12 potentially lucrative nerds and screentests them in front of a few million viewers. When I went on the show, we were given the contact details of literary agents before the first episode had even aired, and given permission to licence the Bake Off roundel for the front of our inevitable cookbook, like a royal seal. By 2016, more than four million cookbooks written by Bake Off alumni had been sold. By now, about 100 Bake Off-adjacent books have been published. In the Great British Bake Off tent, the battenbergs are just a front for the printing press out back.

It reveals something that serious cookbook fanciers don’t like to admit about their recipes, but must: cookbooks – even the most high-minded ones – are ancillary to screens. More recently, printed recipes follow on from Facebook pages, TikTok videos, YouTube channels and blogs. In 2022, Jamie Oliver hosted the Great Cookbook Challenge – a hybrid cooking/reality competition show in which contestants competed for a Penguin cookbook deal. It was axed after the first season, the producers having had the audacity to say the quiet part out loud.

12. 30 Minute Meals, by Jamie Oliver (2010)

The book that changed everything

Few cooks in Britain today understand power as well as Jamie. He understands that cookbooks often don’t have that much power to truly change how people eat – at least not if they work alone. You need supermarket partnerships, product lines, invitations to 10 Downing Street. You need campaigns, and the ear of legislators and producers and press barons. You need something more than just a nice idea for lamb shoulder, which is why the visible Jamie is supported by a mycelial network of recipe testers, researchers, nutritionists, marketing heads and production assistants.

But recipes do change things, sometimes: they can break through the yoke of habit and they can, if nothing else, change other recipes. It’s hard to think of a bigger influence on the language and the rhythm of contemporary British food writing than 30 Minute Meals. It is the best-selling cookbook of the century so far. It’s also where Jamie really perfected his style: a scrappy, kinetic way of cooking and talking about food, both chatty and utterly foolproof. Between the book and the show, he polished the Jamie patois: kissing, chuffing, banging, bunging, whacking, faffing and plonking; sticky, smoky, fiery, tasty, crispy, lovely and herby. Read any supermarket-ready, mass-market cookery book produced in the last 15 years and you’ll notice these beats, those signature Jamie runs. He is the master of marketing a recipe – making the oldest ideas feel new – and this, in a world of seemingly infinite recipes, is how you become the bestselling cookbook author in British history.

13. Plenty, by Yotam Ottolenghi, photography by Jonathan Lovekin (2010)

The book that changed our relationship to vegetarianism and veganism

A recipe writer is lucky if they create just one recipe that people actually make – a recipe that alters, in some tangible way, the course of food culture. Yotam Ottolenghi, with his collaborators, has written or co-written at least four cookbooks that you could credibly accuse of doing just this, but it’s Plenty – the second Ottolenghi cookbook, published in 2010 – that has done the most to change the aspirational diets of middle-class Britain.

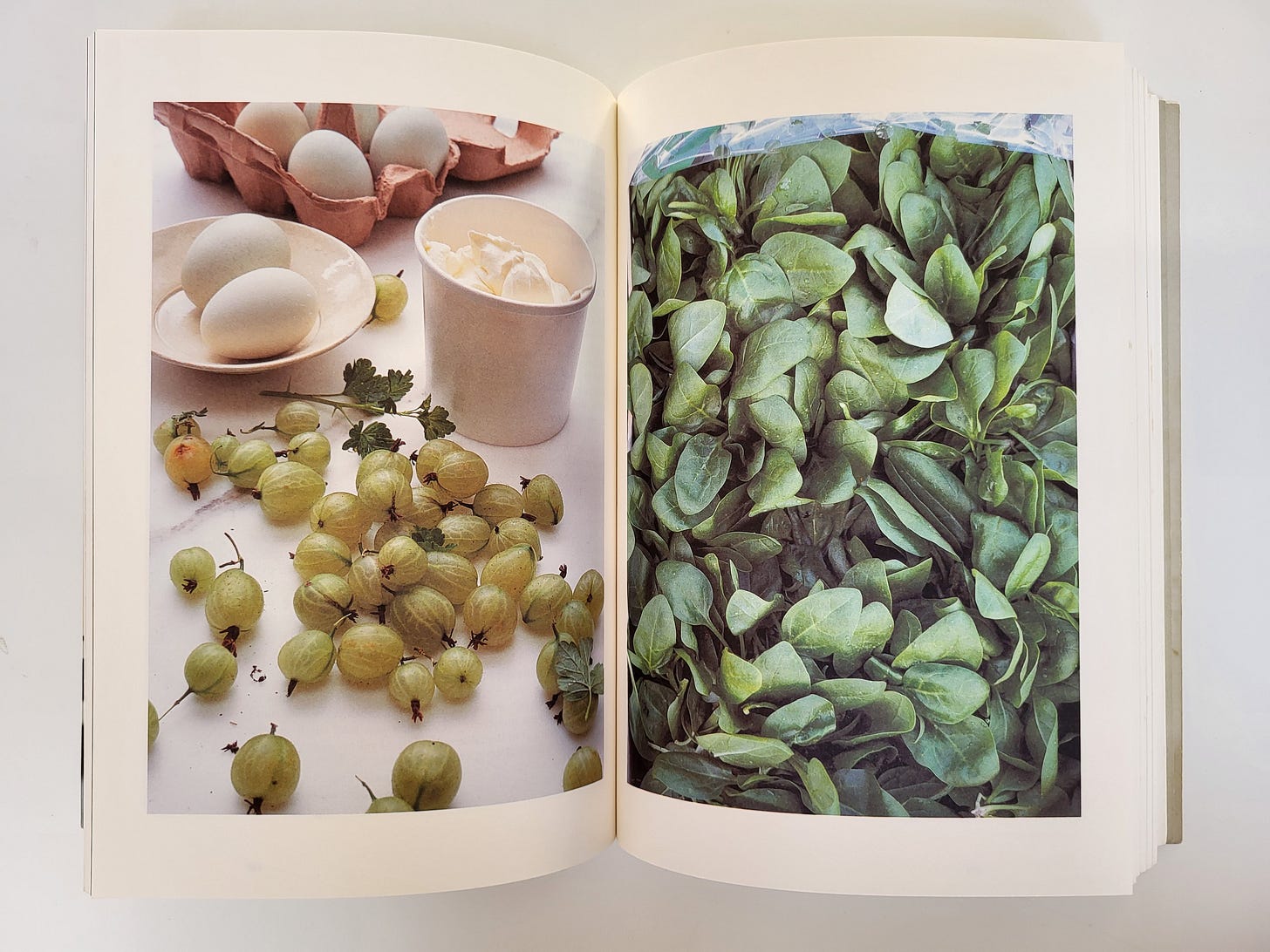

Plenty is an edited collection of pieces from Yotam Ottolenghi’s Guardian column, The New Vegetarian. The ‘new’ really meant something at the time. A ‘mixed grill’ made with kohlrabi and courgettes and turned with parsley oil. Spiced red lentils with cucumber yoghurt. Soba noodles with aubergine and mango. If these recipes sound normal now, it’s because Plenty has done its job – it has course-corrected the recipe culture towards the power of vegetables.

But the real Ottolenghi flex is in the methodology. ‘We never replicate a recipe,’ Ottolenghi once said. ‘We replicate the idea of a dish.’ This one point – the idea of a dish – has since become not just the bedrock of the Ottolenghi philosophy, but the foundation of a modern recipe culture. It’s hard to overstate just how huge this shift of mindset has been. From named dishes to permutations of ingredients, from a cuisine to individual constructions, from time-honoured flavour accords to pick-and-mix blends drawn from a global pantry. It is everywhere. It is Mob, it is za’atar in Waitrose, it’s the many scions of the Ottolenghi Test Kitchen, it’s a whole way of looking at recipes – breaking them down, building them up. ‘I’ll start with something as simple and unassuming as rice,’ Ottolenghi wrote, opening the cookbook that changed it all. ‘I immediately go dizzy with the countless possibilities.’

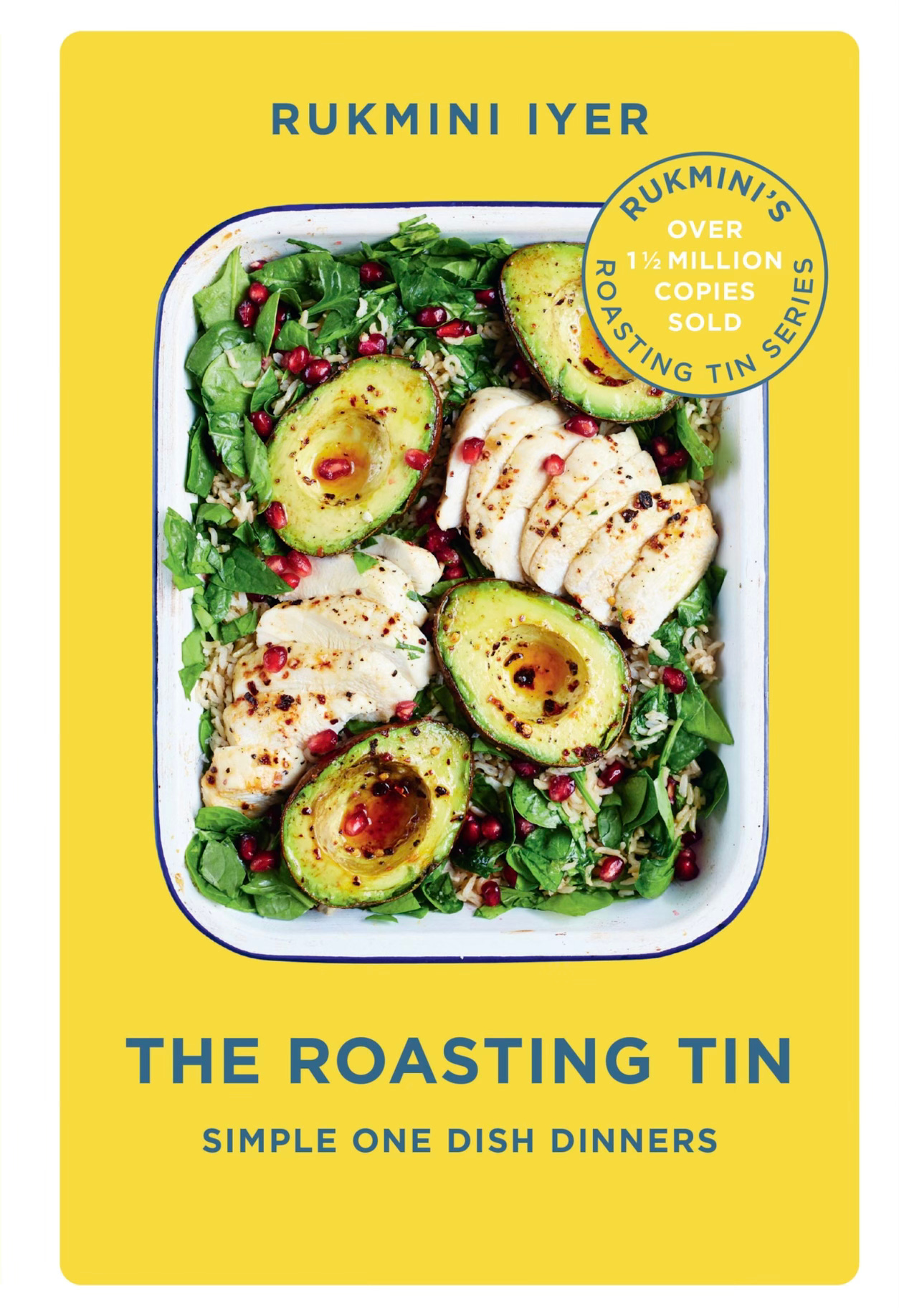

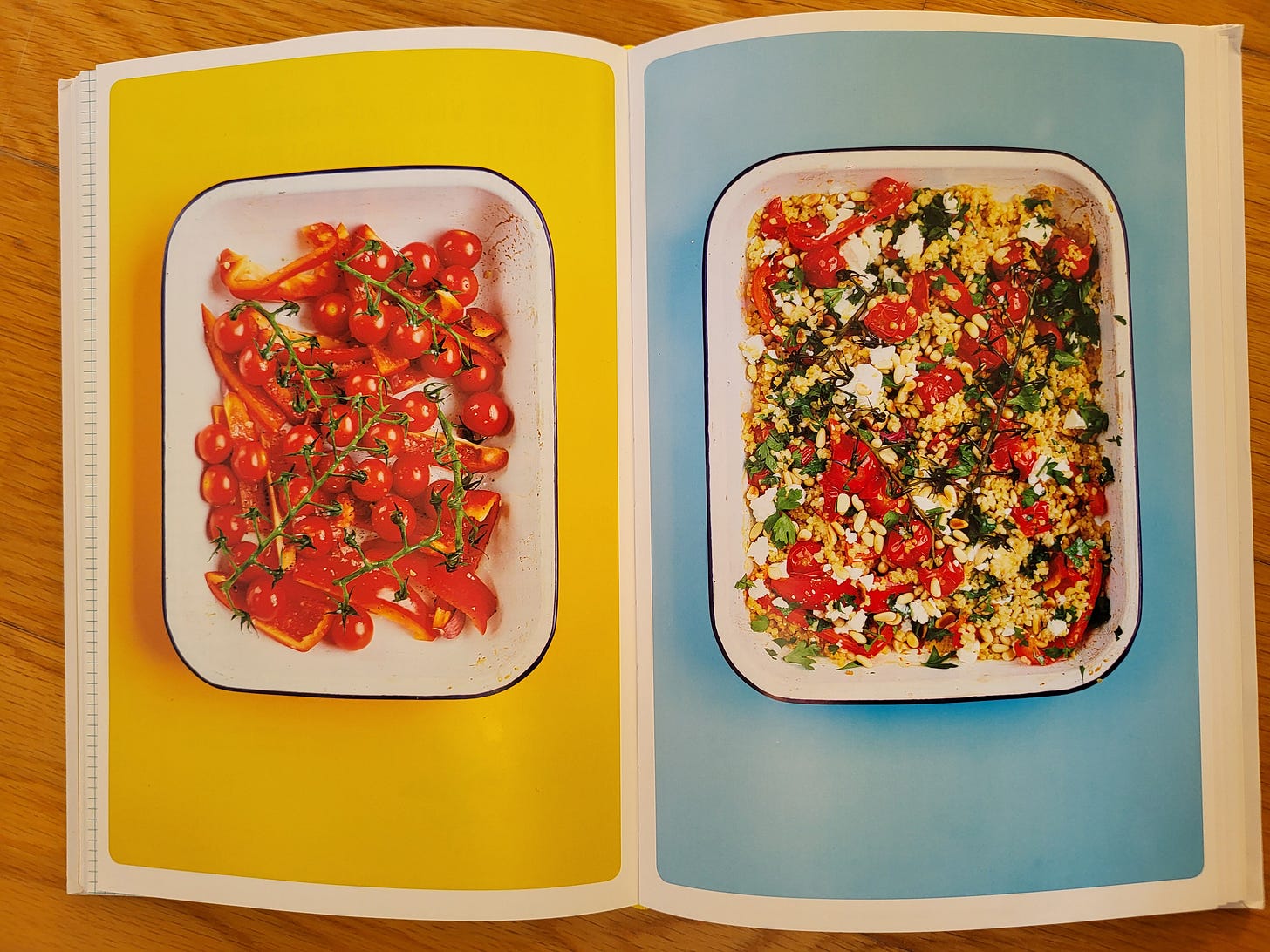

14. The Roasting Tin, by Rukmini Iyer, photography by David Loftus (2017)

The book that changed our ability to cook under pressure

In cooking, you quickly learn that the simplest ideas are often the best. This goes for cake decorating and the making of salads. It also goes for publishing a hit cookbook. Rukmini Iyer’s idea was about as simple as they come: dinner, cooked in a roasting tin. Since then, we’ve had Iyer’s Quick Roasting Tin, Roasting Tin Around the World, Green Roasting Tin and Sweet Roasting Tin, not to mention an entire Roasting Tin dupe industry, from Jamie to Pinch of Nom.

People have been cooking one-pot dinners for as long as they’ve had to bear the cross of washing up, but the aesthetics of Iyer’s books felt fresh. In a broad, flat roasting tin, everything pops: pasta dishes can be presented with expressionistic flair, tomatoes take a char, halloumi crisps and its edges deepen through shades of copper and taupe. David Loftus, one of the most prolific photographers in modern British food, created a world of tightly schematised visual overload: flatlay shots in which the tins become the picture plane. There’s no outside world here, no context, no light and shade, no fuss.

Under the stewardship of cooking authorities such as Harold McGee or Kenji Lopez-Alt, we’ve been conditioned to fear and revere cooking science, but Rukmini’s coup was to realise that you could avoid this worry, for the most part, if you simply shut the oven door. You can even make risotto this way. With 1.75 million copies sold so far, the exhilarating moral of this story is just: do less.

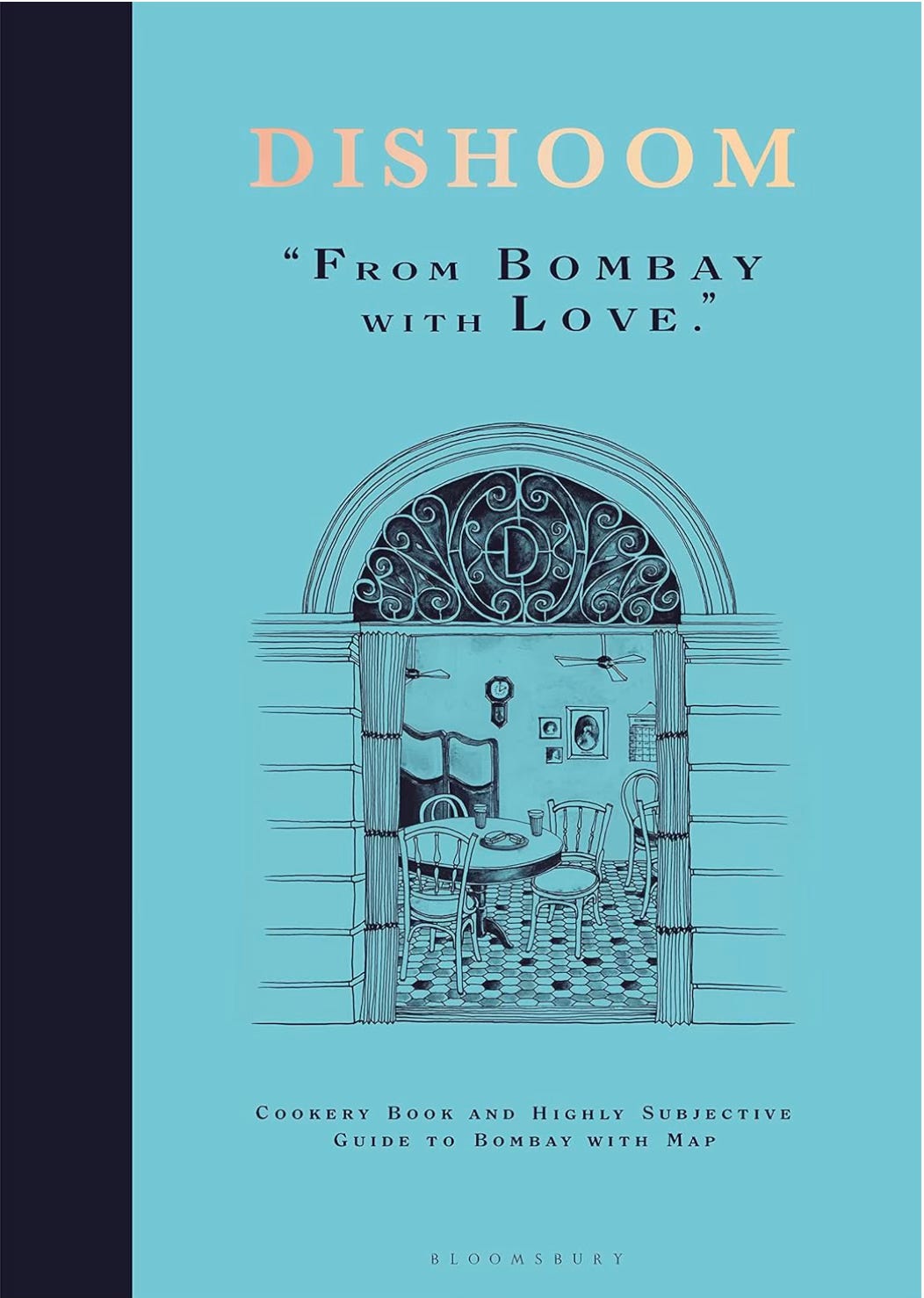

15. Dishoom, by Kavi Thakrar, Naved Nasir and Shamil Thakrar (2019)

The book that changed the influence a restaurant can have through its cookbook

Restaurant cookbooks have been around for a long time. In 1936, SK Cheng of London’s Shanghai Restaurant wrote the Chinese Cookery Book, and EP Veeraswamy – of the restaurant that bears his name, which is now the oldest Indian restaurant in London – published Indian Cookery. In the 1970s, the Cranks cookbook brought vegetarian restaurant food from central London to the suburbs. During the 90s, there was the River Café cookbook, and then Fergus Henderson’s Nose to Tail Eating in the noughties. It can feel like a binary, maybe even the binary upon which British food culture is built: dining out versus home cooking. But restaurants and cookbooks are symbiotic, and the two feed inexorably and circularly into each other’s hype.

It was only ever a matter of time until Dishoom, the most skilful hype-manufacturing, world-building restaurant group of the 2010s, released a cookbook. We have Dishoom chutney sets, Dishoom IPA, Dishoom prints, Dishoom body wash, and the pandemic-era Dishoom bacon naan roll kit. The restaurant has even inspired a parasitic industry of Dishoom-ish supermarket ready meals. The book, written by co-founders Kavi Thakrar and Shamil Thakrar, and chef-director Naved Nasir, was a logical next step. Five years later, in the list of the 100 best-selling cookbooks of 2024, there was only one cookbook about a specific non-western cuisine: Dishoom.

The Dishoom cookbook has all the greatest hits, from the gunpowder potatoes to the house black dal. On Instagram, photos from the home cooks join stories from Americans on nights out at Dishoom King’s Cross. What emerges are not just Dishoom the restaurant and Dishoom the cookbook, but Dishoom the cohesive, omnipresent, ruthlessly effective brand. The book has sold about 300,000 copies in the UK and is still going strong. It’s arguably the most successful restaurant cookbook of the last 20 years.

Credits

Ruby Tandoh is a writer from Essex, currently living in London. She has written for The New Yorker, ELLE, the Guardian and more about food and culture. This article is loosely based on a chapter in her forthcoming book, All Consuming: Why We Eat The Way We Eat Now, out 4 September. You can preorder it here.

This supplement was subedited by Tom Hughes. The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

Love the inclusion of Marguerite Patten’s book on Pressure Cooking here as it was seminal. She was brilliant and generous and gave me lots of good advice and encouragement when I started writing about pressure cookers. However, I do view the 1970s pressure cooker trend with mixed feelings. There are so many horror stories from that time and people have long memories, it has made my job much harder today - the biggest hurdle in pressure cooking today is getting people over the fear factor!

Thank you, Ruby! I thoroughly enjoyed this: “This makes White Heat the cookbook equivalent of Mary Poppins – a film that everybody remembers for one or two memorable songs, but which is, in fact, about banking.”