Death by Duxelles

How modern food culture played a decisive role in the Erin Patterson trial, by Aaron Timms. Illustration by Sing Yun Lee.

Good morning, and welcome to Vittles! We’re very excited that Issue 2 has now gone to print, and we’re selling through the magazine like warm baked goods of some kind. If you wish to guarantee a copy, pre-order the magazine now. If you order before 1 December, you will receive it for a discounted price, with an extra discount for paid subscribers (see the original email for details).

From now until publication day, we will be posting some online-only content related to the subject of Bad Food by various Vittles writers and contributors. See this as the magazine’s extended universe. The first article by Aaron Timms, who wrote about British food influencers for Issue 1, is an investigation of the infamous Erin Patterson trial, and the unlikely influence that modern food culture – from Gordon Ramsay to MasterChef – had on the most bizarre murder of the decade.

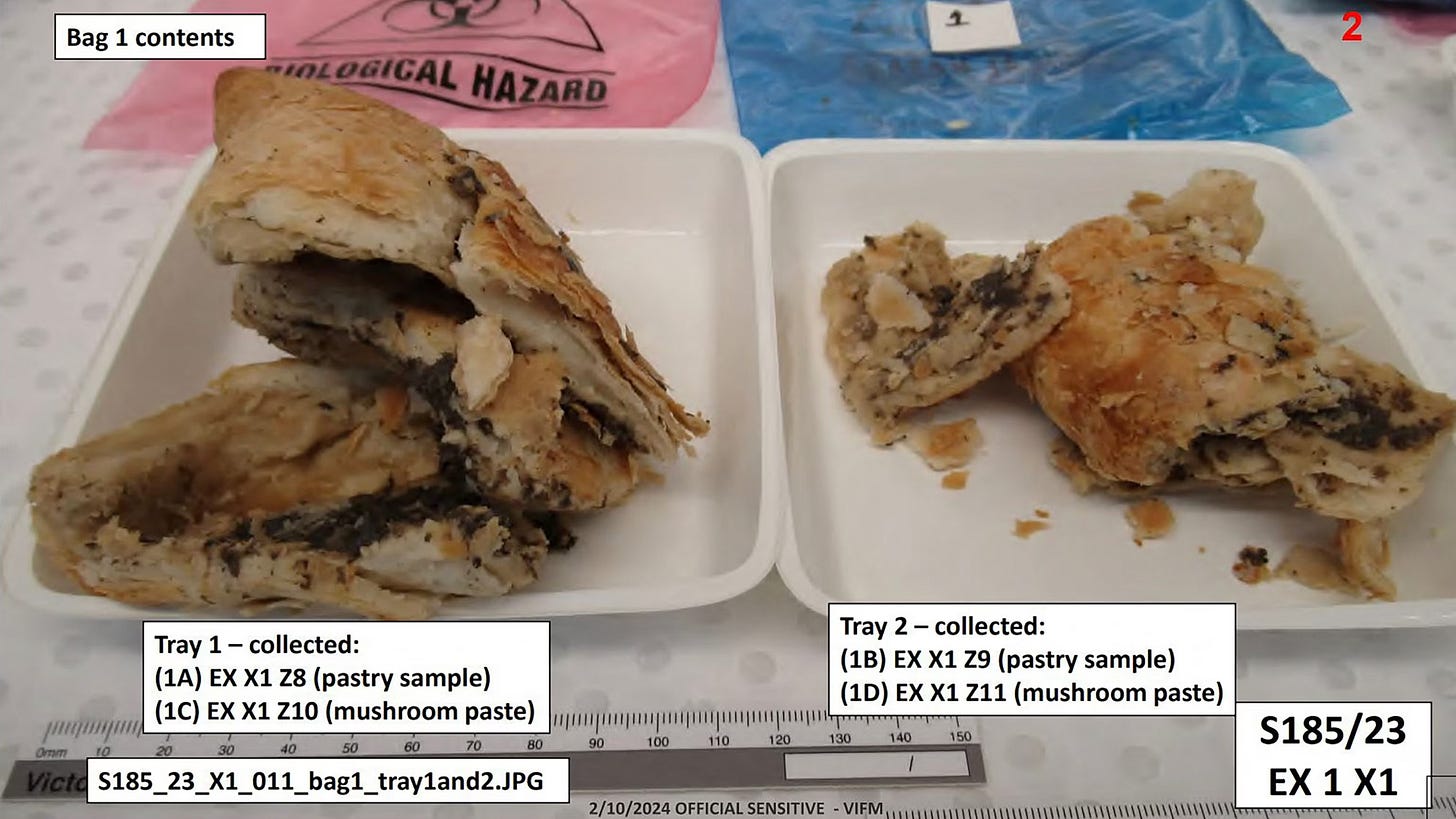

How responsible are we for the dishes we make, or even kill with? If authorship of food is shared, could it be that everyone who’s helped nourish the modern cult of the beef Wellington is in some way responsible for the 2023 murder of three elderly Australians in the Victorian town of Leongatha? That’s taking things too far, of course: Erin Patterson was the sole author of her crime, whereby she fed a small party of relatives a lethal meal of toxic-mushroom-spiked beef Wellington, and for which she was recently sentenced to life in prison. International media coverage throughout the trial was relentless; since then, a torrent of books, TV series and spin-offs has been announced, each of them promising to wade deeper into the mystery of this most unusual triple murder, whose contours are so macabre they seem to have been plucked straight from a short story.

Part of what has made this case so intriguing to so many people across the globe, I believe, is its connection to food. This was a story of culinary disguise, of meat concealed in dough and murder masquerading as lunch. A whole world – of smartphones, competition shows, hottest-ticket-in-town pop-ups, must-have cookbooks, signature dinner party dishes, celebrity chefs forging through the bush and tenderly photographed, pastry-cradled lobes of rested red beef – had to come into being for Patterson’s scheme to assume the precise form that it did. Without such influences, this might have been a murder like any other; instead, it was the first killing in which modern food culture played a decisive architectural role.

For the true-crime fiends, the vital question the case raises is why: why did a seemingly undramatic forty-eight-year-old woman, living in a small, laconic town in the pastures of south-eastern Victoria, invite her in-laws, her mother-in-law’s sister, and the sister’s husband over for lunch, then kill them with the main course? But for the food-fascinated, the more interesting question is how: how did a middle-aged Australian, in the year 2023, come to forage death cap mushrooms and use them as the basis for a poisonous lunch – and what made beef Wellington a suitable vehicle for the accomplishment of her plan? I don’t mean ‘how’ in a narrow instrumental sense, but in a wider cultural sense: what were the specific historical conjunctures that led Patterson to choose, for her victims, death by duxelles?

Exhibit A: The Mushrooms

Over the past two or so decades, Australia – where I was born and grew up – has embraced, with uncommon zeal, food as a source not only of sustenance but also of culture and collective identity. Perhaps this is because the country’s own post-colonisation culinary heritage is fairly thin, or because food is synonymous with the migration that has remade the nation in the decades since World War Two, or because the ancient foodways of the island continent’s indigenous inhabitants were, until recently, poorly understood by the general population. Probably, it’s all three reasons at once. The flat white (and the intense coffee culture that surrounds it), the ‘all-day cafe that serves restaurant-quality food’, the avocado toast: Australia’s obsession with ‘food and bev’ is so powerful that its most recognisable signifiers are now global clichés.

In the past decade, a passion among local chefs for foraging – supercharged by Noma’s relocation to Sydney for a ten-week pop-up in 2016 – has bolstered the restaurant industry’s ‘discovery’ of the continent’s unique and extraordinarily rich plant life, creating a form of hyperlocal, super-tidal cooking that has become a powerful cultural spectacle in its own right. At nearly any moment in Australia today, whether on TV or social media, you’ll find some enterprising young chef performing their appreciation of the continent’s endemic vegetal bounty with the fly-eyed fervour of the recently converted. This spectacle could involve savouring the acidity of a quandong, brandishing a salty necklace of sea grapes or worming through mudflats in search of pigface, sea rush, marine couch or swamp weed.

Patterson’s escapades took place against the backdrop of a nation suddenly mad for foraging – or at least dead keen on the idea of a trained professional doing it for them. Death caps are not, I probably don’t need to point out, the type of thing Australians usually like to harvest for their own consumption. But thanks to the species identification tool on iNaturalist – a photo-based, user-sourced biodiversity platform that includes more than 300 million observations of plants and other organisms worldwide – they’re relatively easy to identify. Indeed, Patterson relied on iNaturalist to scout her noxious haul, diverting users’ cautionary tagging of death caps on the platform towards a far darker end.

The story of how death caps came to exist in Australia to begin with has much deeper roots. Amanita phalloides is not native to Australia; the species was introduced in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as the result of an effort to Europeanise – or more precisely, Anglicise – the evergreen continent’s southern cities. The early colonists of Australia felt that British trees were superior to all others, and that all public parks should be planted in the British style (as directed by a resolution from the Victorian Gardeners’ Mutual Improvement Society in 1862). Evergreens like the native eucalyptus tree, as a host of nineteenth-century observers recorded, were felt to be ‘too gloomy, dirty, and dense’, ‘too towering and ragged’, too ‘monotonous’ for the new cities of southern Australia. ‘Other things being equal,’ one such observer wrote in the bulletin of the Victorian Department of Agriculture in 1889, ‘deciduous trees are to be preferred.’ The legacy of that preference can be seen in cities like Melbourne and Canberra today, which have a density of oaks, elms, poplars and plane trees in their centres and wealthy suburbs utterly at odds with the native Australian landscape’s unvarying palette of blue, brown and beige.

This provincially Eurocentric desire to ‘improve the face of the country’ (as colonial Victoria’s chief secretary put it in 1870) by planting deciduous trees throughout its temperate southern towns and cities also had the effect of creating a biotope uniquely hospitable to the death cap mushroom, which flourishes in the rhizosphere of the oak tree in particular. According to mycologists, death caps travel to foreign environments as fungal bodies known as mycelia on the roots of introduced trees, then propagate once planted in native soil via mushrooms and spores; their introduction, in other words, is the accidental by-product of arboricultural policy. The iNaturalist distribution map shows quite clearly the clustering of death caps in cities like Canberra and Melbourne, and around the towns south-east of Melbourne, where Patterson went foraging. This map not only offers a remarkable visualisation of the fungal legacy of colonialism, it also shows how history and technology came together to make Patterson’s murder plan possible, affording her both access to a nearby mushroom supply and the convenience of a user-friendly app with which to score its deadliest treasures.

Exhibit B: The Wellington

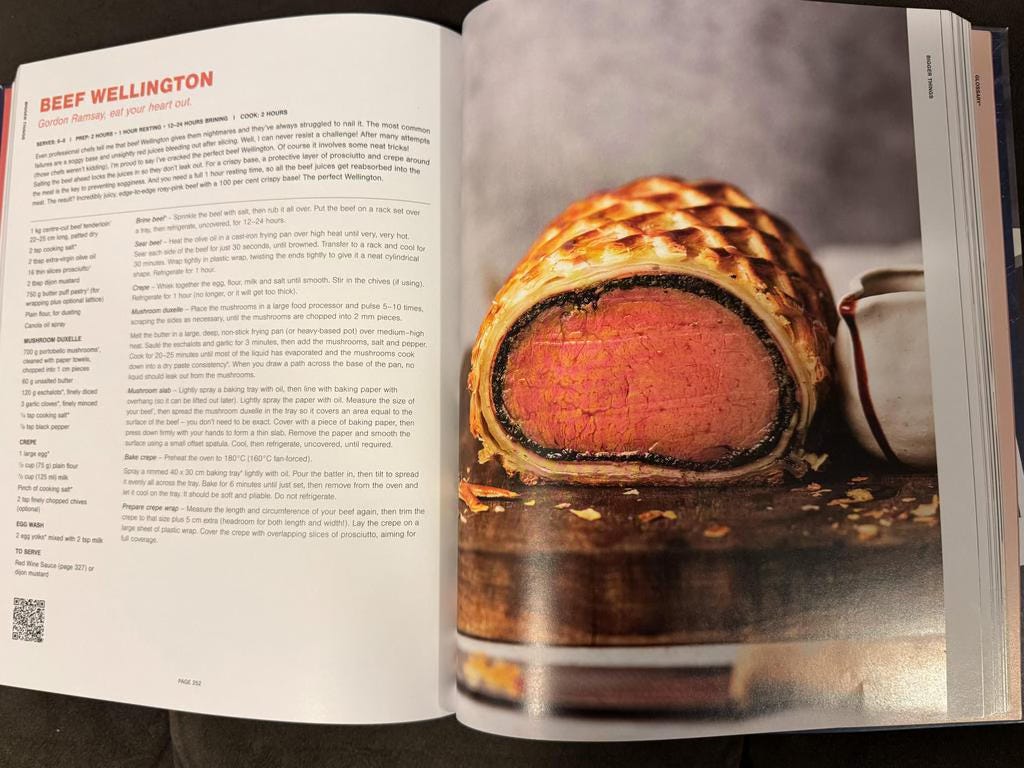

Beef Wellington is a dish that, like the trees that gave Australia death caps, traces its origins to England. While its connection to Arthur Wellesley, the first Duke of Wellington, is inconclusive, the scholarly consensus is that the dish earned its name, and took distinct and recognisable shape, in the grand hotel and palace kitchens of England and Europe at some point over the course of the nineteenth century. In recent decades the dish has been repopularised thanks to social media and the work of celebrity chefs like Gordon Ramsay, who’ve turned it into a global symbol of luxury and excess, standardising the dish as a chateaubriand log of consistent thickness which is sliced open to reveal its blushing meat.

Ramsay is a judge on MasterChef Australia, the most-watched food competition show on Australian TV. The programme has featured beef Wellington prominently over its seventeen seasons – partly because it’s a good measure of a cook’s skill in handling multiple components and cooking styles at once, but mostly, I suspect, because the food internet has made the dish perennially vibey. Though Ramsay has not, as far as I know, directly presided over a beef-Wellington-themed challenge, his ideas about what constitutes good cooking permeate the show, as does his signature dish: in recent seasons, beef Wellington has inspired a portrait challenge, a reinvention test and various manipulations, where the Wellington’s beef has been substituted for pork and beets.

We don’t know whether Patterson is a fan of MasterChef, but all murders reflect culture back to itself. Australia’s food fanaticism, of which MasterChef is a central pillar, would unquestionably have lent credibility to the killer’s baked steak theatrics: the preparation of such an elaborate dish legitimised her in the role of both cook and peacemaker. Patterson extended the lunch invitation to her in-laws out of the blue, after several years throughout which their relationship had grown icy; the husband of her mother-in-law’s sister, the meal’s sole surviving victim, said during the trial that the invitees all happily accepted in the hope that the gathering might prompt a thaw. Beef Wellington is a dish designed to dazzle and comfort at once. It offered the perfect cover for Patterson’s plan, dressing intent to kill in the flaky drapery of a culinary showstopper.

The folklore at the heart of MasterChef in Australia is that great cooks can come from anywhere. As in the UK (and in contrast to the US, where the pros-only Top Chef reigns supreme), Australia’s pre-eminent competitive cooking show opens its doors to both amateur and professional chefs. The recurrent spectacle of the ‘humble home cook’ wowing the betoqued and terrifying MasterChef judges with feats of unexpected kitchen wizardry has imprinted itself on the national cultural consciousness as evidence of Australia’s unique gift for gastronomic invention. Beef Wellington is a tricky dish to pull off: there’s a real art to cooking the pastry (which should be buttery, golden and light) and the pill of beef hidden inside (whose cuisson cannot be tested by touch) at the same time. Patterson’s attempt of a dish like this showed a spontaneity, a confidence, an ambition entirely consistent with the surrounding culture’s mythos of the virtuoso home cook; walking into her house that fatal day, her guests likely greeted the sight of beef Wellington on the plate with delight rather than horror. Food culture made Patterson’s meat-and-mushroom murder weapon believable as a symbol of skill, care, respect and reconciliation.

Exhibit C: The Recipe

There’s another dimension to responsibility in this case that food, normally a stranger to criminal procedure, invites us to anatomise: the question of attribution. Patterson followed a recipe for beef Wellington from RecipeTin Eats: Dinner, a tome by chef-blogger-influencer Nagi Maehashi that is said to be the fastest-selling cookbook in Australian publishing history. The recipe from the book nods explicitly to Ramsay in its sub-heading (‘Gordon Ramsay, eat your heart out’). Interestingly, Patterson departed from the recipe’s instruction to construct the dish as the single, sliceable cylinder canonised by Ramsay and his ilk. Instead, she assembled a series of individual Wellingtons, which allowed her to control the allotment of poison to each of her guests while serving herself a plate that was toxin-free. We live in an era of hacks and mods, of cooks in the comments endlessly sure of their ability to improve upon the printed instructions with shortcuts and switch-outs. Patterson was not the first home cook to deviate from the recipe, but she was surely the first to make the deviation deadly.

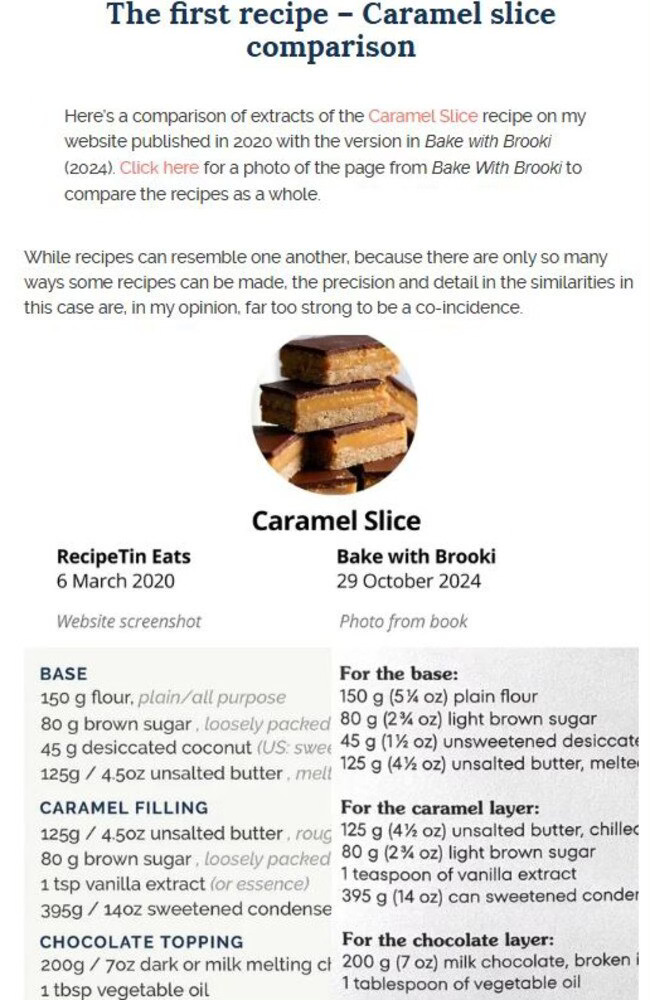

Earlier this year, Maehashi accused the Brisbane-based influencer Brooke Bellamy, better known on Instagram and TikTok as @brookibakehouse, of plagiarising her recipes for caramel slice and baklava. Caramel slice is a classic and beloved Australian dessert, the type of sugary treat that can be found in bakeries all over the country; baklava is, well, baklava. The similarities between Bellamy’s recipes and Maehashi’s ‘originals’ may be striking – the ingredients, proportions and directions are all essentially the same – but attribution in these cases surely attaches to no one; though countries may claim ownership of baklava, no individual can. If caramel slice ‘belongs’ to Maehashi, does beef Wellington belong to Ramsay, to the army of unheralded nineteenth-century cooks who collectively wrestled the dish into something like its modern form – to the Duke of Wellington himself? The debate over authorship that Maehashi’s allegations triggered took place, curiously, right as Patterson’s trial was starting, a coincidence that practically wills us to consider one theft (of two recipes) in light of the other (of three lives).

Recipes are not subject to copyright or ownership in any meaningful sense, legal or otherwise; they are only ever a rough translation of a physical act that every reader completes with their own cooking. They bring both author and reader into a community – of shared experience, knowledge and feeling. Some languages even grammaticise the collective nature of recipe-writing (and recipe-following) by framing directions not in the imperative, as is conventional for recipes in English, but in the present tense of the first person plural (‘We season the beef …’). The death cap mushroom and its arboreal host thrive through a symbiotic association known as a mycorrhiza, sustaining and even communicating with each other via the exchange of nutrients and other matter. At its best, the act of cooking functions in much the same way, as an expression of reciprocity and fellow feeling that creates bonds of mutual nourishment.

But very occasionally, the marriage curdles, the glue of community turns toxic, and we get something like the Patterson case. Life cedes to death, symbiosis to synnecrosis; food becomes foe. Though the court’s guilty verdict was unambiguous, the mushroom murders sprouted from a rich historical sediment of taste formation and communal enthusiasm. The killer alone was responsible for these deaths, but culture made them possible.

Credits

Aaron Timms is a writer living in New York.

Sing Yun Lee is an artist and illustrator based in Essex who specialises in painting, drawing and collage. You can find more of her work on her website and on her Instagram.

The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

this is one of very few Vittles essays I have found a bit drab and unconvincing, more a lay of the land of white australian food culture than anything more insightful.

Not sure the thesis stands up to rational scrutiny — and a town cannot be laconic. But I enjoyed the read.