Eating in bed, a lyric essay

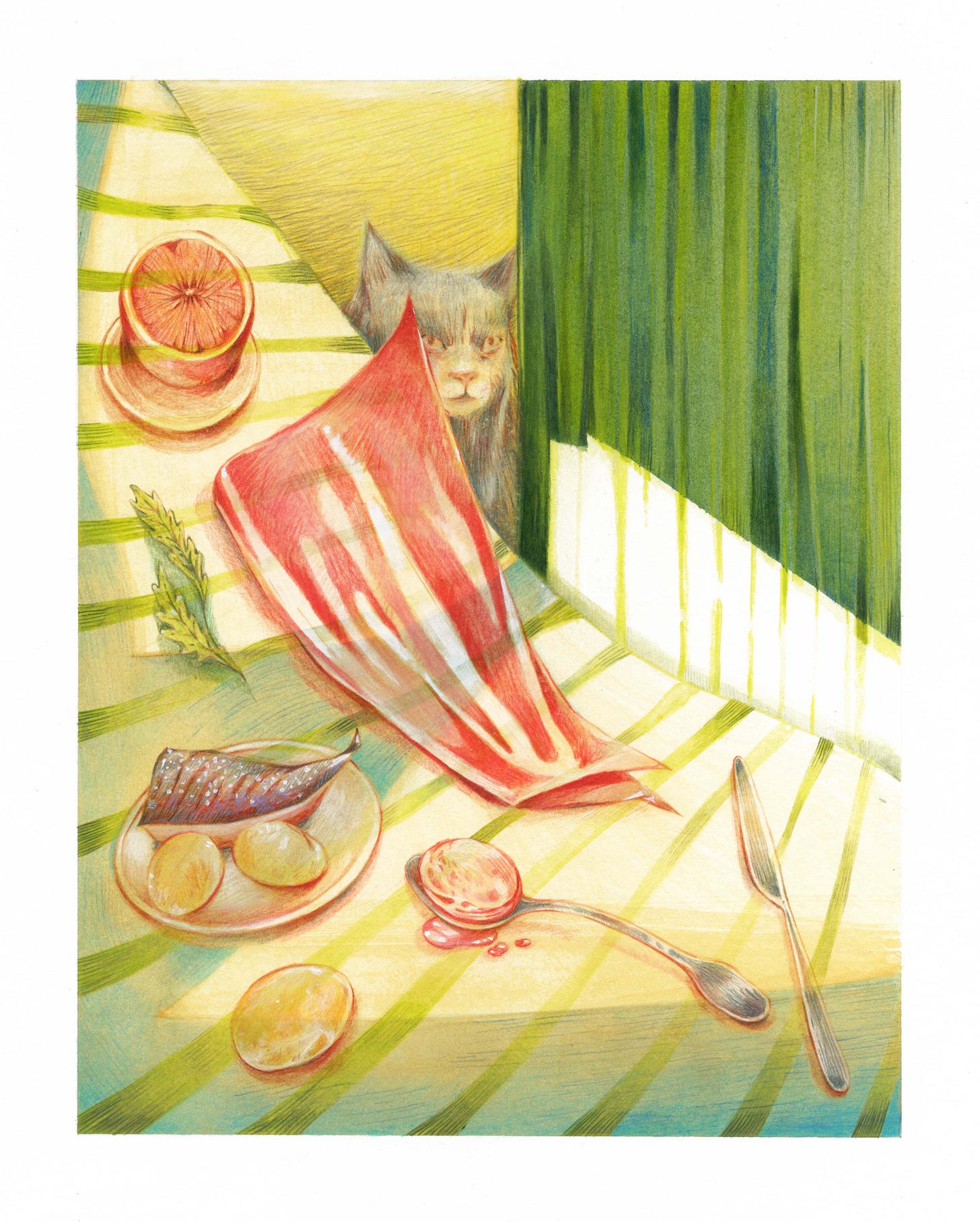

Jo Hamya on meals in bed. Illustration by Sing Yun Lee.

Good morning, and welcome to Vittles! Today’s essay is by novelist Jo Hamya, who writes about eating in bed.

If you wish to access all paywalled articles in full, including Vittles Cooking on Wednesday and Vittles Restaurants on Friday, then please subscribe below for £7/month or £59/year. Each subscription helps us to pay writers fairly and gives you access to our entire back catalogue.

Eating in bed: a lyric essay

Jo Hamya on meals in bed. Illustration by Sing Yun Lee.

1.

Because I am still grasping my way out of a dream about pregnancy – blue fluid in the womb, a set of twins already born but they are not mine, I didn’t labour, my child is still inside – he gets out of bed first. When he comes back, it is with coffee and Alphonso mangos. He halves and scores the fruit with a knife. They are faintly nice, but out of season. We agree not to be greedy next time, to wait until June.

We eat. Everything quiet. There is the faint buzz of a podcast coming out of his earphones and the jagged whisper of pages turning in the books I am browsing while I decide what to write; the intermittent drop of mango skins onto a plate resting between us. Our unspoken agreement, as on most Sundays, to spend the first half of the day in bed – him on top of the duvet, me under it, the cat at our feet. I reciprocate his breakfast with lunch some hours later by chopping basil, tomatoes, and mozzarella in the kitchen and spreading them over rocket. I add oil and salt. I take this meagre offering back to the bedroom in silver bowls. No, he says, it’s good.

2.

We don’t eat in bed every day. We spent much of last week taking meals somewhat dutifully in the living room: on the sofa, in the armchair, on the floor. But I don’t like eating there. It reminds me that we don’t have a dining room table, or rather, that we don’t have a flat large enough for one. My feeling is that we return to eating in bed because our bed defies the rest of the small, crumbling Victorian flat we live in. It has been lavished with a kind of care we aren’t able to perform on the ceiling (which leaks), or the kitchen (which was partially dismantled for inspection and never repaired), or the flooring (which is, in places, barely existent).

By contrast, the bed is king-sized. It has a heavy, black, wrought-iron frame. A pocket sprung cashmere mattress stuffed with sheep’s wool. Once a week, we place our duck-feather duvet inside freshly laundered percale cotton bedding, candy striped in cream and ochre. We light lamps and position ewers of orange flowers around us. We draw back a makeshift curtain of mossy green velvet over the single-glazed window above our heads in the morning and close it again at night. Our bed is a nice place to be. It is, as Bachelard says, a living nest. We come back to it every day, we dream of coming back to it, the way a bird comes back to its nest, returning for meals, for conversations, for sleep, for sex.

When, in The Poetics of Space, Bachelard says the nest is a bird’s very person, I know intimately what he means. The absence of a dinner table in our flat might sting, but even when I did have one in another flat, I started the day at it sober with two soft-boiled eggs and ended the day tipsy and horizontal on pillows, scooping mayonnaise from the bottom of a chicken burger with my fingers. I seared lamb chops and set out cutlery on a flat, wooden surface for friends in the early stages of an evening, only to end up waving away apologies for flecks of pavlova on the comforter around midnight. A dinner table has formalities a bed does not. It gives us pleasure to eat in bed. A pleasure to be with, to dine with, those you love there.

3.

I spend the lull after lunch glued to my phone, looking up ‘interpretation: pregnancy dreams’, ‘nests + pregnancy dreams’, ‘+bed’, ‘+hungry’. I divine little from the results. There are blogs on personal growth, on life changes, on anxiety. Advice on hunger pangs; links for pregnancy pillows and baby beds, neither of which I need. A few articles on bursts of energy and a strong desire to clean, which I read surrounded by stray cutlery and dog-eared books.

4.

So instead I read a biography of Virginia Woolf’s time at Asheham House, which quotes part of a letter to Lady Ottoline Morrell. Please don’t treat me as an invalid, she says. Save for breakfast in bed (which is now a luxury and not a necessity) I do exactly as others do. It’s a line worth lingering over. Eating in bed, not as the sign of an invalid, but as the sign of one who has the luxury of doing so. At some point in the past year, I began to think of entire meals as ‘delicious little treats’ because they were eaten between sheets. A plate of herring and boiled potatoes. A bag of calamari, bought on a whim, dredged in flour and fried, with homemade tartar sauce on the side. In our household we seldom have lunch in bed, which means we seldom have lunch at all. One or both of us is usually out of the house, and it will occur to me then, passing salad bars on the way to meetings, sending emails from an armchair, that I have little remaining interest in carving out intervals for an efficient meal between working hours as others do. I want the slow indulgence of eating on a mattress I have bought with the person I love, now top-and-tailed, passing a bag of sweets between us at the end of a busy day; now elbow to elbow, picking at toast, listening to the radio to put off the start of another.

5.

Mess is most people’s deterrent against this kind of dining. But mess is an excellent barometer for mood or a relationship. In that closed, intimate space, without table manners and convenience as a guide, how forgiving are you of yourself or others for ordinary slips in dexterity, for ordinary accidents? Anything can be laundered. Everything can be dusted down; cleaned. What sort of rage, or mirth, or ambivalence are you confronted with should the sheets end up temporarily stained with soup? In the early days of our relationship, I would preface meals with large trays and pink napkins stolen from Brasserie Zédel. I would swear and run for damp sponges and detergent if mess happened. He would calmly continue eating.

These days, little to no food falls on the bed. No trays, no napkins anymore. Another kind of etiquette in their place. He is sure to take care, and I am sure to look past his occasional spills. He has always loved me enough to never comment on mine. I now try to match this kind of love: silent, poker-faced. It is a conscious effort, and sometimes, for me, hard to sustain. So it happens that when things are not going well, I forget to maintain this kind of wilful blindness and we argue. But if hot oil comes squirting fast out of an onion ring after a particularly good night out, I laugh delightedly, and he laughs with me. He fetches the detergent. I tell him it’s laundry day anyway.

6.

At ten to eight, the question of dinner comes up. We have long abandoned our intended plan for the afternoon – to go to Richmond Park, to admire tawny deer and tawny trees with flasks of rum and cassoulet. We could still go for a walk closer to home, but in his words, ‘It’s cold out there and nice in here: I want to go out, but I don’t’. We agree to freeze the cassoulet for better weather.

Because he is gently stoned, he suggests ordering from the Italian restaurant around the corner from us – an occasional habit of mine when I don’t want my writing interrupted by cooking or cleaning. He usually considers this indulgent and wasteful. Today, I smile beneficently and bring my phone closer to him. I pretend not to know the menu well. I point out pizzas streaked with pistachio pesto and mortadella; braised beef with polenta. He will have none of it. What if the pizza comes smashed? What if the polenta isn’t soft enough? We should eat those things in the restaurant where we can send them back, he tells me. It doesn’t make sense to eat them now, in bed.

This is true. In a way, our etiquette for eating has come to mirror our etiquette for sex. New, exciting things happen in the living room or outside the house. If they disappoint, we return to the bed. Familiar, well-trodden ground which never threatens to disappoint. Via this logic, we order the pappardelle with beef fillet ragu he likes and tagliatelle bolognese, which I have had twice before. I throw in a box of salad and a dessert as an afterthought.

Since the pasta, when it arrives, is served in cardboard bowls, we are able to move freely. He eats reclining; I eat cross-legged. We leave the large red bag delivery bag in at the foot of the bed. Into it hops the cat, who now understands that we prefer him to investigate the new, exotic smells he detects when take-out is delivered via the medium of sniffing the bag, as opposed to the medium of smashing his face into our food while he decides whether or not he would like to eat it. Perhaps this is one disadvantage of the bed: moving the cat to the other side of it is less effective than dropping him from a table would be when it comes to preventing this behaviour. Still, the bag and a small tray of treats work well as a pacifier; also, they allow us a hygienic and less chaotic illusion of eating as a family, which we all ultimately want.

I go back to thinking about my dream, about the impossibility of doing this with a baby. Well, some small voice contradicts me. You’d probably breastfeed here for a while if you did give birth. Some women bed-share. Some women might accidentally drop crumbs of ciambella, marbled with cocoa and poppy seeds, on their infant’s head.

7.

Something else Bachelard says – there is nothing more absurd than images that attribute human qualities to a nest.

It is difficult for me to tell whether what we are doing is fine or whether we are being, simply, a little absurd. I want to say the former, for obvious reasons. I do not want to be ridiculous. I do not want to spend each day crouching in the living room. I want our nest. To Bachelard, at least, making one seems to involve a dialectics of forest love and love in a city room; something attainable only after the initial mad flush of love, when concepts like logic and longevity have kicked in.

Hence those sensible thoughts we express to each other after three years of sharing a flat. They come unconvincingly, and not very often. We should rearrange the living room to fit a dining table in. Difficult to say where it would go among my writing desk, his gardening tools – the sofa, the books, the TV, the cat’s scratch pole, his bowl for wet food. Our flat is small; there is not enough space. There is no way of differentiating space, no ‘upstairs’ for our respective makeshift offices, away from the ‘downstairs’ of the dining room, the kitchen. In the city, Bachelard writes, homes become mere horizontality: it is hard for them to acquire those fundamental principles for distinguishing and classifying the values of intimacy.

We should move to a bigger flat. We will, eventually, if one of us ever comes into the kind of money that would permit it, or if a child forced us to. We should leave the city, test Bachelard’s belief in Ménard’s theory, that in the forest, I am my entire self … Thickly wooded distance separates me from moral code and cities. But we are, already, ourselves, and happy with our respective moral codes. We smile and quarrel at the similarities and differences between them all the time; our relationship is stronger for it. We just wonder, every few months, whether it wouldn’t be nice to have a table where we could host a dinner party. We never manage to follow through, and we blend the intimacy found in our bed with our food. We prop ourselves up against pillows and share spoonfuls of ice cream; tell the cat sternly that it’s bad for him while, to our barely concealed enchantment, he slurps little shavings off the lid.

8.

What I take Bachelard to mean when he mentions the dialectics of building a nest: an unsentimental way of creating shelter in an otherwise hostile environment. What we started almost three years ago, thanks to the cramped parameters of our peeling living room.

We have turned our bed into a nest by eating in it. We have turned having a nest into our own private language of consideration. At quarter past eleven he brings me a red grapefruit, sugared like a jewel, to bed. I have spent my day here, writing this, eating more than I usually would, trying to inhabit what I mean.

I mean this: being given this glittering, difficult-to-eat pink thing by the person I love. It shoots liquid every time I dig my spoon in. We cluck and giggle over it. We spend our mornings and nights bringing each other these offerings in the place we rest our heads, choosing them with some small extravagance in mind, in the hope it will make us feel nice. A piece of bread with black truffle butter, a fistful of blueberries. Roasted pork, bowls of scotch broth. Little kisses we bring to each other’s mouths. I care about you, is what they represent. I want you to know that I care.

Credits

Jo Hamya is the author of the novels Three Rooms and The Hypocrite.

Sing Yun Lee is an illustrator and graphic designer based in Essex. You can find more of her work here.

The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

Just beautiful, and what a beautiful relationship x

Wow. Beautiful.