It’s ‘Fasul’ and Yes, I’m Saying it Right

Monica Cardenas on cooking her mother’s dishes after decades of estrangement

Good morning, and welcome back to Vittles! In case you missed it, we published the Vittles 99 last week — our list of the best restaurants in London right now. You can now read the guide in full, with all addresses added, here.

In today’s newsletter, Monica Cardenas has written for our Cooking from Life column, a series of essays that provide a window into how food and kitchen-life work for different people. Monica portrays the challenge of recreating her mother’s dishes in the wake of their estrangement.

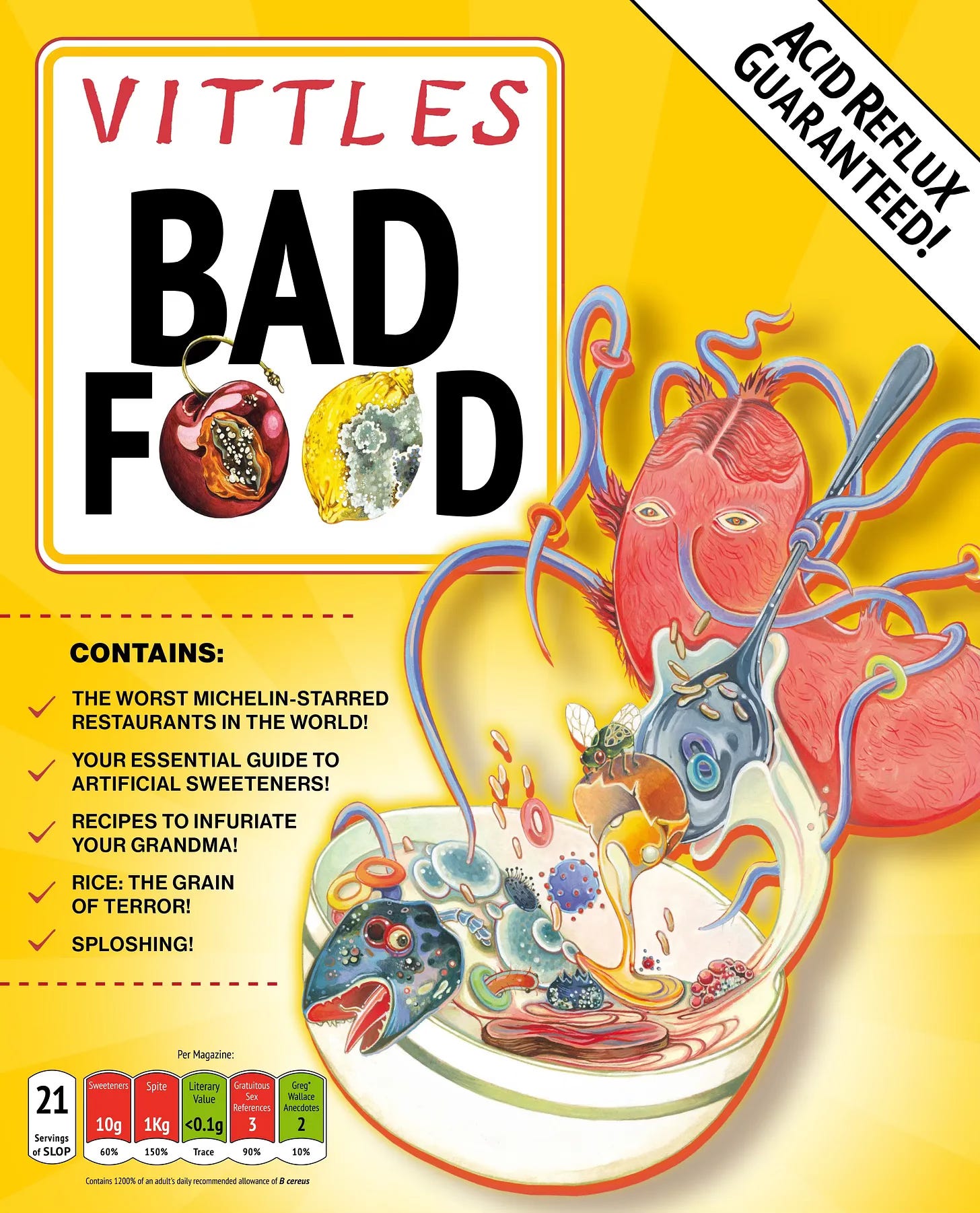

Also, a reminder that this is the last week you can buy a copy of Issue 2 of our print magazine to guarantee it arrives before Christmas (if you are in the UK). You can buy the magazine on our website here, along with prints from our favourite illustrators and photographers. If you have pre-ordered a magazine for Christmas and it hasn’t arrived yet, then please let us know and we will sort it out.

Do we peel the cucumbers for mac salad? Do we add salt to the zucchini breading, or just salt it at the end? My sisters and I ping these kinds of questions around in our group chat, ‘4 Non Blondes’. What we mean is: How do we cook this like Mom? Our resources are our memories, and trial and error. We haven’t had a relationship with our mom for almost twenty years – all of our adult lives, and some of my younger sisters’ teen years, too. But even though she is no longer there for us, and many childhood memories are far from comforting, those familiar tastes and smells can still release a spell of contentment.

My mother never followed a recipe from a cookbook or tried anything new. There were no advanced techniques or special equipment in our kitchen (except that one time she splurged on the apple corer-peeler that spun an apple into a slippery white slinky). Her repertoire was beef stew, chicken and rice, lasagne, fried zucchini, Spanish rice, macaroni salad and her homemade riff on Hamburger Helper. She used onion and garlic powder. We drank Lipton iced tea, mixed from a tall canister that came with its own scoop, and used the crumbly, artificial kind of parmesan cheese.

‘“How do we cook this like Mom?” Our resources are our memories, and trial and error. We haven’t had a relationship with our mom for almost twenty years.’

My sisters and I cobble together favourite childhood meals based on vague memories of which spice jars came out of the cabinet (oregano, we think), or what we regularly picked up at the grocery store – large cans of crushed tomatoes were always on the bottom shelf, and as kids we’d heave them like kettlebells to our chest. Although it has been decades since we last ate Mom’s food, when we’re able to capture exactly the right flavour, texture, consistency – it’s thrilling.

But there is one recipe of hers I’ve always struggled to get exactly right. Perhaps the problem with pasta fasul, as we called it at home (more commonly known as pasta e fagioli), is that it appears simpler than it is – a few high-quality and specific ingredients, and a particular technique that eluded me for years. I’ve spent the better part of a decade trying to figure out how to make it like she did.

If you order pasta e fagioli at Olive Garden, a popular Italian chain in the United States, you’ll get soup. The restaurant’s version is a tomato broth with kidney beans and ground beef, all of which is very different from the thick, vegetarian dish with white cannellini beans my mother always prepared.

So, the first time I visited Italy, I scoured menus for it, eager to get a taste of the real thing – the dish my mom used to make. It was understandable that a fake Italian restaurant in America got it wrong, but surely in Florence it would be like home.

Wrong. What I received was nothing like the dish I grew up eating. The Florentine version had the white beans, at least, but it was still too soupy.

This was in the early aughts, when my mother and I were in the first stage of our estrangement and everything about her felt unanswerable. If the soup I was served in Italy was the ‘real’ thing, then what had my mother been cooking all those years? And were we even really Italian?

‘I found an article from the 1970s in the local newspaper about my ancestors’ family reunion …The article explained that the matriarch had immigrated to Pennsylvania from Guardia Lombardi, Italy. An answer.’

The small town in northeastern Pennsylvania where I grew up was teeming with people who called themselves Italian, but for how many generations can a person identify this way without any actual experience of living in Italy or within an Italian culture?

I found an article from the 1970s in the local newspaper about my ancestors’ family reunion. It was big ‘news’ because, at the time, there were nearly 150 descendants of my great-great-grandparents. The article explained that the matriarch had immigrated to Pennsylvania from Guardia Lombardi, Italy. An answer. Her daughter, my great-grandmother, married another Italian immigrant, and my grandmother married a man whose heritage I can’t quite trace.

I was still a bit unsure about my roots, given the apparent inaccuracy of one of my family’s signature dishes. I always felt that my Italian genes were greatly diminished by the time they reached me, and while my father’s Peruvian genes were evident on my face, as a first-generation immigrant, he was more focused on being American than passing on his heritage. Meanwhile, my mother bought our pasta from a little old lady who made it in her house, dried it, and delicately boxed it in long, thick strands. (In keeping with Mom’s miserly ingredient preferences, this was still cheaper than Barilla.) Distant aunts and uncles – my great-great-grandparents’ fifteen children – died at regular intervals, and we mourned each of them in exactly the same way: viewing in the evening, mass in the morning and burial, followed by a baked ziti and vinegary salad brunch in the church hall. We went to mass Sunday mornings, and in the afternoons ate spaghetti in Great-Nana’s basement.

So even if Mom’s pasta wasn’t ‘right’ – it feels like an integral part of my heritage.

Most nights I cook for two, but when I’m alone I gather the ingredients that I remember Mom using for pasta fasul. Crushed tomatoes, ditalini, cannellini beans. Good olive oil. Real onion and garlic – for this dish she didn’t scrimp.

Ditalini doesn’t have a good stand-in. It’s like a very small rigatoni. A tube about the size of my pinky nail. Shells and elbows and even farfalle are too big and too much, and the little stars you sometimes see in soups are far too small.

Despite the care I take in sourcing the same ingredients as my mother, the end result has never been quite what I recall. And since there’s no one I can ask for my family recipe, I turned to a professional chef I met in Italy on a recent trip.

‘What can you tell me about pasta fasul?’ I asked her.

‘You say it correctly!’ she exclaimed.

I was baffled. ‘I do?’ I assumed my pronunciation – copied from my mother and a full syllable short – was the result of the Italian ‘fagioli’, mangled over the generations, like in a game of Telephone. But she explained that ‘fasul’ comes from the Naples region, while everyone else in Italy calls it fagioli. I opened a map, and there, yes, was Guardia Lombardi, just centimetres from Naples. An answer.

‘But what about the tomatoes?’ I asked. ‘My mother’s always had a tomato sauce.’

She told me everyone makes it differently. Her Neapolitan grandfather would sometimes use the juice from only one tomato, whereas I distinctly remember a full can of crushed tomatoes going into the pot. Then my new mentor added: ‘Sometimes people cook the pasta in the tomatoes.’ Another answer.

All these years, I’d been making a sauce then adding the cooked pasta. That was the wrong way around.

Days after I returned from that trip to Italy, ditalini simmered away in a pot of tomato broth and my kitchen filled with familiar smells. Before I even tasted it, I gave it a stir and said aloud, ‘This is right.’

The satisfaction that comes with successfully recreating one of Mom’s recipes is always fleeting. Just like my journey to understanding our estrangement, the answers I find only offer a glimpse of a tapestry I’ll never see whole. It’s taken me years to come to terms with our broken relationship, but her food is a safe remembrance: I can choose when to open the door to those memories, and when to close it.

Pasta Fasul

Serves 6

Time 35 mins

Ingredients

2 tbsp olive oil

1 medium onion, diced

2 garlic cloves, chopped

1 tsp dried oregano

salt

2 x 400g jars of tomato passata or cans of crushed tomatoes

1 x 400g of cannellini beans in water

450g ditalini pasta

Method

Heat a large, deep pan over low heat. Add the olive oil. When the oil is hot, add the onion and stir. After 2–3 mins, add the garlic and oregano, salt generously and stir again.

Once the onions are softened, but not browned, add the passata or crushed tomatoes. Refill the jars or cans with cold water and add to the pot, then bring to a simmer. Add more salt, then the can of cannellini beans (including their liquid) and the ditalini.

Simmer, uncovered, stirring frequently to ensure ditalini doesn’t stick for about 15 mins or until al dente. If the mixture thickens too much as you cook, just add more water.

Take off the heat. Cover with a lid and leave to rest for 10 mins while it thickens, then serve.

Credits

Monica Cardenas holds an MA and PhD in Creative Writing from Royal Holloway, University of London. She authors the Bad Mothers newsletter, and hosts a sister podcast on maternal estrangement. Her work has been published in The Audacity, Huffington Post, Literary Hub and Litro, among others. Originally from the US, she resides in Chiltern Hills near London.

The Vittles masthead can be viewed here.

I love this! I totally went through this slow process of discovering cooking as an enactment of memory, and decrypting bits of language and taste that are very regionally or family-specific.

'Fasul' comes from the dialect spoken in Guardia Lombardi - but why is 'Guardia Lombardi' called that? I imagine it was a Lombardian settler outpost that maybe infused that particular part of Campania with strange little Lombardian customs that maybe one day made it to America too

Nice article, and the name must have come from some of the people who passed through the Naples area in the past.

"Fassoulia (also spelled fasolia or fasulye) means "beans" in Arabic, Greek, and Turkish.