Melek Erdal’s Baked Candied Pumpkin with Tahini and Walnuts

A soft, sweet cure for heartbreak, first eaten in a 7/24 autostop canteen in Antalya. Words and photos by Melek Erdal.

A Vittles subscription costs £5/month or £45/year. If you’ve been enjoying the writing, then please consider subscribing to keep it running. It will give you access to the whole Vittles back catalogue, including Vittles Restaurants, Vittles Columns, and Seasons 1–7 of our themed essays.

Welcome to Vittles Recipes! This week’s columnist is Melek Erdal. You can read our archive of cookery writing here.

Melek Erdal’s Baked Candied Pumpkin with Tahini and Walnuts

A soft, sweet cure for heartbreak, first eaten in a 7/24 autostop canteen in Antalya

‘A meal with salça [tomato paste] and a woman with kalça [hips],’ he said cheekily, as the plate of candied pumpkin arrived at the table. We were at a 7/24 köfte piyaz canteen at an autostop on the way back from visiting the ancient city of Perge in Antalya. They say 7/24, not 24/7, here, and I think about what that might do to one’s perception of time, the order in which you eat things. Uncle Fahri – or Professor Fahri Işik – is a leading archeologist in the southwest of Turkey, excavating ancient cities and fighting for them to become protected heritage sites. He had noticed that my spirit and appetite had dimmed since our previous meeting. Maybe he thought the pumpkin would revive me, or that the outdated phrase would startle me back to life. The professor was unconventional in the way he spoke, brazen and unrepentant but well intentioned – and intentional. He was making a point: he didn’t deem it worthwhile to lose my appetite over a break-up. Eat first, reminisce later, 7/24.

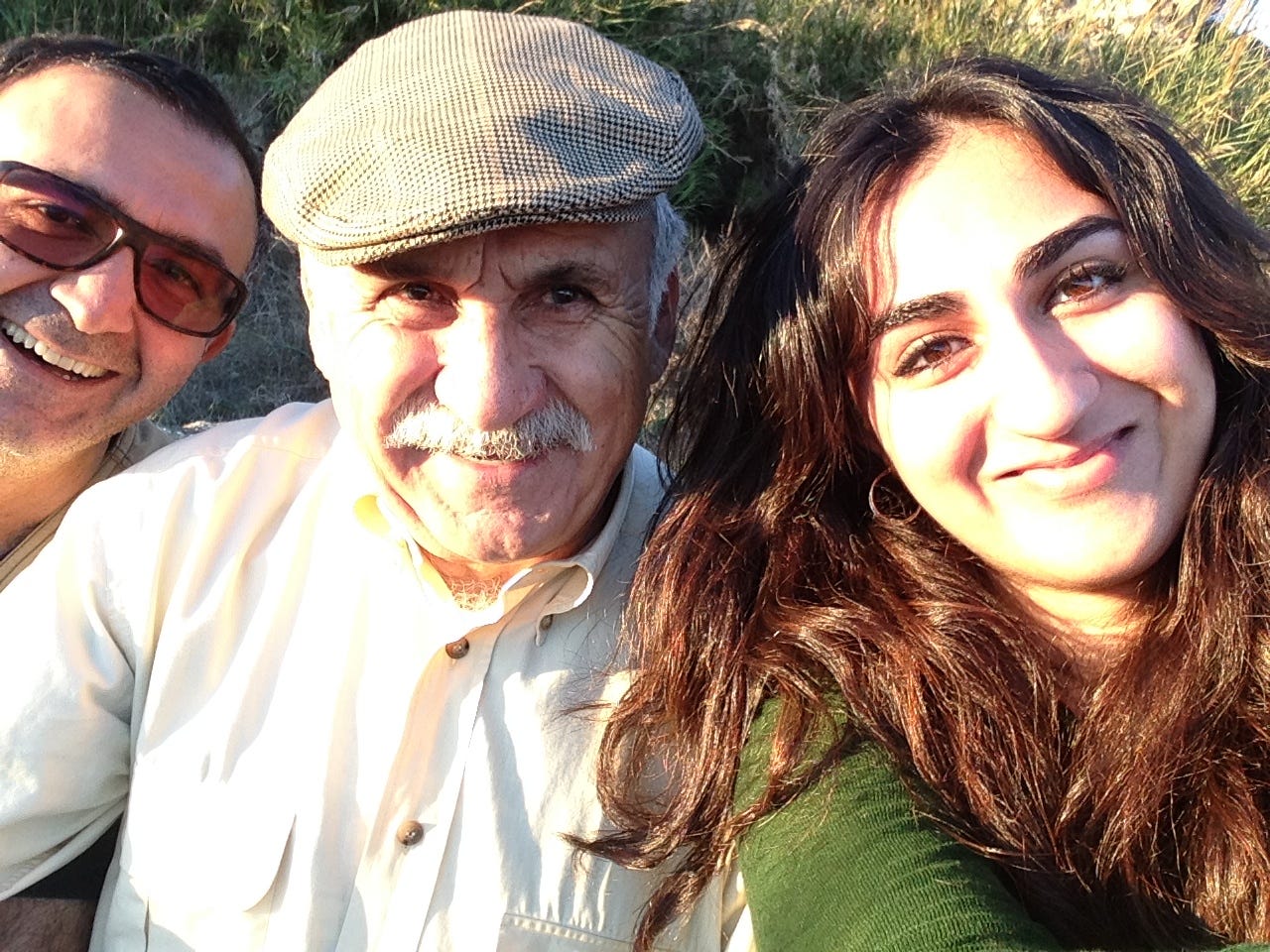

I’d first met Fahri a few years before, back in 2012. I was visiting my uncle, Murat, who was excited to introduce me to his best friend, who was teaching students at the ancient site of Patara, near Kaș. He walked up to us on the pristine beach, hands behind his back, flat cap, short-sleeved shirt, pen in the breast pocket. The look of a rural boy of Malatya hadn’t left him, yet he had made the beach life adapt to him, strolling across the sand as if it were solid ground. We hit it off instantly.

My partner was with me, but Fahri was uninterested in him, and took me by the arm to tell me about his journey into archaeology. His mother raised him and his three siblings on her own, putting them through school and then university – an uncommon achievement. His brother became a famous actor and presenter of the Turkish version of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? – the late, great Kenan Işık. ‘How wonderful for you to be with a woman smarter than you,’ Fahri said to my partner, patting him on the shoulder and swiftly continuing with his tour of the site. He mentioned his wife at the tail end of every comment, referring to her as his lover, or ‘Havva’m’ (‘my Havva’). Havva means ‘Eve’. How perfect, I thought, since he spoke like she was the first and only woman.

When I returned to Antalya in 2015 without my lover, I was seeking comfort with Murat and the professor – two loving, protective, and incredibly funny men who gave me what I needed to mend a broken heart. We walked around Perge entirely alone (it was closed for the season) in the low October sunlight, with the professor regaling us with the site’s history, claiming passionately that civilisation started in Anatolia. He turned to me and said, ‘How is that wretched ex of yours?’, his voice echoing round the amphitheater. I giggled. My ex was likely skateboarding somewhere, his new hobby. Kurds don’t skateboard, I thought, so I sang back, ‘I don’t know.’ He murmured the swear word ‘sefil’ (meaning ‘miserable’) under his breath and suggested heading to the autostop on the way home to have a treat. I was grateful for the anger I did not yet feel. I had lost the cafe I had built in the breakup and I was sad about this. I fantasised about Fahri fighting to excavate and protect my cafe, the same way he fought for these ancient sites.

Antalya motorway canteens are famous for their köfte piyaz, a delicious, lightly spiced lamb and beef köfte sometimes made with tail fat or crotch fat (yeah, it’s a thing apparently). These köfte are usually served with a side of white beans in tahini, lemon, and vinegar, topped with fresh tomato, onion, and parsley with thin ‘tarak’ flatbreads. But uncle Fahri swore by the kabak tatlisi – a dessert of baked candied pumpkin drizzled with tahini and covered in ground walnuts that was also synonymous with the region.

I sliced into the jammy pumpkin with my spoon, scooping up some tahini and walnuts too. Uncle Fahri looked at me with a smile, as if he knew something I didn’t. ‘He didn’t pull off that moustache, either,’ he said, as I stuffed my mouth with the richly sweet dessert, straining a gulp as I laughed out loud. How beautifully the nutty tahini encased the pumpkin that was almost too sweet, how welcome the crunch of the walnuts against the softness. I thought about how much I loved these men, with whom I felt known and seen.

A few years after eating pumpkin at the autostop, I got a call from the professor. He said he had a package on its way to me. His lack of faith in the postal system was so ingrained that it took three friends travelling through four cities over six months to get to me. The package was finally hand delivered by a lovely man called Aziz, who drove from Portsmouth to my door in London to drop it off. I opened it to find a book, Fahri’s book, titled Civilization Started in Anatolia. I smiled, remembering our tour of Perge as I looked at the dense, mammoth book, his life’s work, which I knew I wasn’t going to read (my Turkish doesn’t flow like that). But I will make the pumpkin in honour of the book’s journey, I thought.

Cutting up the pumpkin is the hardest part of making the dish, so I always start by sharpening my knife. The knife you pick is important: it must be a large, hardy one with a strong handle but not so thick a blade that it will get stuck and struggle to glide back out of the pumpkin. Midway through cutting and peeling the pumpkin, you might contemplate your life choices, but push through. I lay out my prepared pumpkin wedges on a tray and sprinkle sugar on top like there has been a heavy day of snow. I leave them overnight and when I return the next day, the snow has melted and turned into sugary pumpkin juice, which I stew the pumpkin in before baking.

I serve with a generous drizzle of tahini and a heavy sprinkle of ground walnuts, which I toast beforehand to balance the intense sweetness of the pumpkin. I take a slice with a spoon, making sure I get a bit of everything. I remember uncle Fahri in the glow of the low October sun, against the backdrop of his ancient city. And I think of my ex and his moustache that was too big for his face.

Kabak Tatlisi (Baked Candied Pumpkin with Tahini and Walnuts)

Serves 6

Time 2 hrs 30 mins plus overnight cooling