Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 7: Food and Policy. Each essay in this season investigates how policy intersects with eating, cooking, and life. If you wish to receive the Monday newsletter for free each week, or to also receive Vittles Recipes on Wednesday and Vittles Restaurants on Friday for £5 a month or £45 a year, then please subscribe below.

For our eighteenth piece in this season, Robbie Armstrong writes about a new food venue on the Isle of Bute in Scotland that raises questions about neo-feudalism, the merits of aristocratic altruism, and the limits of land-reform policy in Scotland.

The Marquess and the Market

Bute Yard, Scottish land reform, and neofeudalism. Words by Robbie Armstrong.

Note: this newsletter has been updated with comment which can be found after the article.

The Market

On a sunny summer afternoon in Rothesay, the main town on the small island of Bute, a modern market that looks much like any other in Britain is underway. The capacious modern barn that houses it is tucked half a kilometre up the hill from the promenade, with stalls from a gin distillery, local bakers, a small-batch cocktail company, and a coffee cabin. One vendor sells Largie, a Caerphilly-style cheese made in Argyll using Bute milk. Another, run by a pair of young Syrians whose family came to the island as part of the UK’s refugee resettlement scheme, sells dolma, kibbeh, fatayer, and baklava. Outside, in the courtyard, there’s a snaking queue for tacos and a line curling out of a smokehouse set up in a shipping container. Towards the back there’s a stall heaving with wicker baskets of fruit and cratefuls of vegetables.

Since opening last June, the market, christened Bute Yard, has been celebrated in the press for providing ‘a platform to showcase the best taste and talent the island has to offer’ and cited as integral to the renaissance of one of ‘the world’s top under-the-radar islands’. It presents a modern and democratic image of Bute. Vendors of various backgrounds and ages – both established businesses and nascent passion projects – are selling produce from across the island, or from as far as Glasgow, some forty miles east. Bute Yard’s success has been so rapid that it now competes for tourists’ attention with Mount Stuart House – the grand, neo-gothic ancestral home of the Stuarts of Bute.

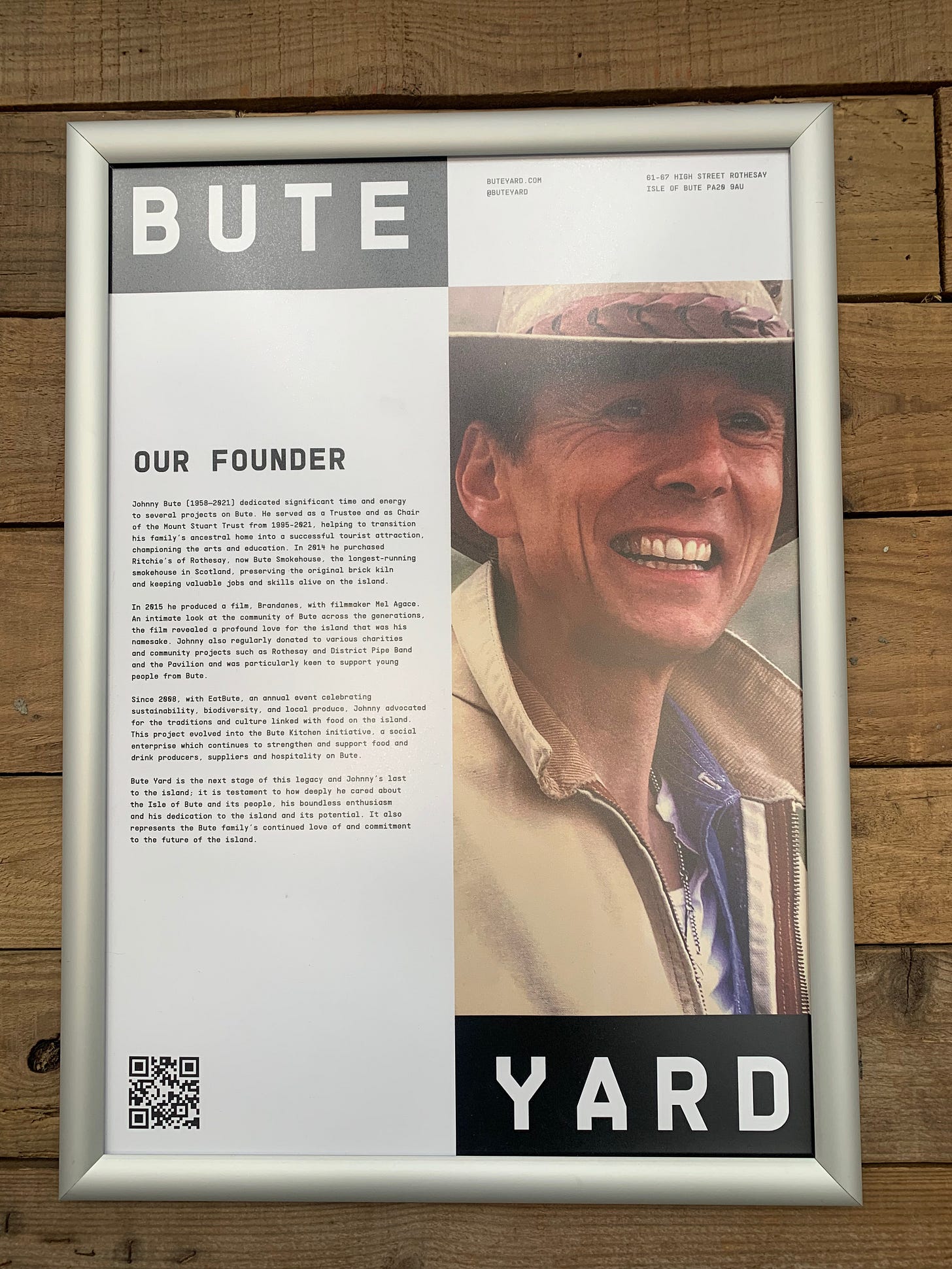

On the surface, Mount Stuart represents Old Bute, while the ultra-modern Bute Yard represents the New. Both, in fact, are the same Bute, since the market is the latest in a long line of projects by the island’s ruling family, the Crichton-Stuarts. Not only does the fruit and veg on display come from the market garden of Mount Stuart, but Bute Yard’s director is Cathleen Crichton-Stuart, the second daughter of the late 7th Marquess, John Colum Crichton-Stuart, better known as Johnny Bute. Bute Yard was founded by Johnny Bute and is owned by his second wife, Serena – the Marchioness of Bute. For centuries, the family has benefited from a quasi-monopoly on the island’s land and resources. Collectively, the Crichton-Stuarts and the Mount Stuart Trust (MST) – a charitable trust that the family retains close control over – own 89% of the Bute’s land. Bute Fabrics, a major employer, was started by the 5th Marquess. The Isle of Bute Smokehouse, one of the oldest in Scotland, was bought by Johnny Bute in 2014, and is now also run by Cathleen. But Bute Yard, according to a panel on the wall, is the crowning piece in her father’s legacy, ‘a testament to his dedication to the island’.

The question asked by many of the island’s residents is, ‘Who does Bute Yard really serve?’ Parts of Rothesay are among the most deprived neighbourhoods in Scotland, although in 2022, the Sunday Times urged its readers to ‘look past the pockets of deprivation’ when it named Bute the best place to live in Scotland. Some of my earliest memories are of holidays spent on Bute as a child, in the mid-nineties, long after Bute’s heyday as a Victorian seaside resort had faded, but before the high street had sunk further into decline. I remember eating Zavaroni’s ice cream on the promenade, playing in the arcades, beachcombing with my dad – but I never forgot the grinding poverty in the housing scheme where we stayed. Returning to the island in 2019, I was shocked to see the extent of Rothesay’s abandoned buildings and crumbling Victoriana. Since then, Bute Yard has become emblematic of a new phase in Rothesay’s regeneration, improving the island’s general appeal to holiday-makers, day-trippers, and people wishing to move here to benefit from the relatively cheap rent and island life.

However, given the MST and Crichton-Stuarts’ near-total ownership of the entire island, any serious conversation about regeneration on Bute – particularly when it involves food and farming – inevitably raises questions about land ownership. The ownership of Bute also places Bute Yard at the crux of many issues concerning all of rural Scotland. Since the Scottish parliament was reestablished in 1999, it has introduced a raft of policies to reform land ownership, including the much-celebrated Community Right to Buy (CRtB) legislation, as well as creating the Scottish Land Fund and the Scottish Land Commission. This month, it published its updated Land Reform Bill, which aims to ‘revolutionise land ownership in Scotland’, while previously the Scottish Land Commission has accused some of Scotland’s hereditary lairds of behaving like ‘socially corrosive’ monopolies. Meanwhile in 2022, the Scottish government also passed its Good Food Nation Act, by which it hopes to turn Scotland into a place where ‘people from every walk of life take pride and pleasure in, and benefit from, the food they produce, buy, cook, serve, and eat each day’.

Standing in the way of both food and land reform policy is the fact that around 433 private landowners own over half the private land in rural Scotland according to research by land-reform campaigner Andy Wightman. This unequal distribution of land has its roots in the Highlands Clearances, during which the predominantly Gaelic-speaking populations were forcibly evicted from the Highlands and islands to make way for sheep farming between 1750 to 1860. Since then, expulsion, landlordism, enclosures, and aristocratic field sports have all changed the relationship Scotland’s people have with their land. This bizarre state of affairs means that, according to Wightman, ‘Scotland has the most concentrated pattern of land ownership in Europe’, which dictates how people live, eat, and interact with the land. How can Scotland really become a ‘Good Food Nation’ with a neo-feudal oligarchy at the helm of its rural land?

The Marquess

Although the island boasts warm waters and incongruous palm trees, Bute is Scotland writ large, with sparsely populated highlands, a densely populated central belt, and a patchwork of monocultural farmland in the south. It suffers chiefly from a lack of affordable and family-suitable housing (but no lack of holiday accommodation and second homes), as well as a depopulation crisis, a shortage of job and higher education opportunities, and stark inequality between its poorest and richest inhabitants.

As part of one of Scotland’s oldest landowning families, Johnny Bute inherited an endowment somewhere in the region of £144 million when he became the Marquess of Bute in 1991 (as a marquess, he ranked above an earl but below a duke in the aristocratic league table). In 1989, his father, the 6th Marquess, vested Mount Stuart and the Bute Estate into the charitable MST. At this point, the family owned approximately 28,000 of the island’s 30,190 acres – 23,800 of which were to be run by the trust. (Andy Wightman has claimed that the MST was created ‘in order to avoid inheritance tax liabilities’). Johnny Bute soon sold the neighbouring island of Great Cumbrae in 1999 for £1 million, washing his hands of it just in time to circumvent new Scottish land laws that would increase the power of sitting tenants. (‘No,’ he told the Independent at the time, ‘I never considered giving the land to them.’)

By the time Johnny died in 2021, the family fortune had swollen beyond £413 million, not including Mount Stuart House. Johnny Bute’s only son, John Bryson Crichton-Stuart, who goes by Jack Dumfries, is the 8th Marquess of Bute. He lives an unassuming life with his family, far from the island in London. He paints Warhammer in his spare time and describes himself as ‘a chef’. Since November 2020, Johnny’s sister Sophie Crichton-Stuart has been the chair of the MST, running the trust with a board of directors including her brother, Anthony. When I speak to Cathleen, she reaffirms that Bute Yard is her father’s legacy. ‘He really, really wanted to do something that was for the community. Instead of trying to lead a horse to water to drink, he’d learnt to maybe just provide a space [Bute Yard] that could organically grow,’ she explains.

Appraisals of Bute Yard vary from positive to pessimistic, depending on whom you ask. ‘I think there’s a bit more confidence amongst the producers on the island because they’re seeing other people are making it, and it’s making other people believe in themselves more,” says Mhairi Mackenzie, who owns Isle of Bute Coffee, and is also one of the directors of Bute Kitchen – a social enterprise that aims to promote the island’s food and drink. Not everyone is so laudatory. ‘Who is using Bute Yard, is it the people with the most poverty on the island?’ asks Nadia Shaikh, a land justice activist based in Rothesay. ‘What I think the Bute population probably really does need is genuine equity between people … and the means of generating wealth and power ultimately is land,’ she adds.

As I chat to people about Bute Yard, I am disheartened to find that almost anyone else with anything even slightly critical to say about the Crichton-Stuarts, the MST, or Bute Yard, is anxious to remain anonymous. A 2012 survey of tenant farmers on the island previously showed overwhelming dissatisfaction with the MST, mainly due to the short duration of their tenancies. Ian Dickson, an MST tenant and contract farmer (and the only farmer who would speak to me on record), admits the trust has made mistakes in the past, but is positive about the MST today (since 2019, it has brought in five new tenant farmers, offering them longer tenures of twenty years.)

Long-standing Brandanes (residents of Bute) tend to be more conservative when it comes to land ownership, and are more likely to take a positive stance towards the Crichton-Stuarts. I got a general sense that, because an aristocratic oligarchy has ruled Bute for so long, they felt that this is the island’s natural order. I am repeatedly told that Johnny Bute was an approachable and unpretentious man, and that the island’s problems lay not with him, but rather with the system of land management on the island itself. Bute’s newer inhabitants tend to be more critical. One resident, who has been on Bute for the last seven years and wishes to remain anonymous, tells me, ‘I like living here, but it makes you feel like you’re still part of the feudal system – the UK is more like that than many realise.’

Another resident, Daniel1, who moved to Bute two years ago, is unconvinced that Bute Yard will fix any of Bute’s underlying problems. ‘It’s not a space that locals can rent at affordable rates … It’s not a community-based initiative, it doesn’t have community at its heart – it’s only got money at its heart,’ he adds. Daniel also explains that doing business is difficult without the backing of the Crichton-Stuart family. ‘Without a distinct change in land rights, and how it’s been consolidated into the hands of a few powerful people, as a community and public, we stand little chance of developing our lives and businesses,’ he argues. ‘We’ve got to hold these landowners responsible, they can’t just cream off the profit – their Instagrams are full of them at Harrods and obscene displays of luxury, meanwhile people on the island are using food banks. It’s morally bankrupt.’

Good Food Nation?

Last July, I paid a visit to the Anchor Tavern, a pub in the small coastal village of Port Bannatyne, just a few miles north of Rothesay. The year prior, 267 people backed a community share offer to rescue the vacant pub in the fastest CRtB Scotland has ever seen, coming together in fifteen months. A few miles further north is Moss Wood, Scotland’s largest community forest, which is part of Rhubodach Forest. In 2009, it was bought from its then-landowner, Richard Attenborough, using CRtB legislation. Johnny Bute had made a bid of almost £1.6 million for the forest, but the Scottish Government flexed its new land reform powers to block the purchase, giving locals the right of first refusal. The money was raised by buying Rhubodach Forest for £1.475 million then selling part to the Mount Stuart Estate for £1.25m. (Tallwood Ltd, owned by the marchioness, owns 1,316 acres of Rhubodach.)

CRtB legislation was introduced in 2003, giving communities the right to purchase land in their area, with funding provided by the government-backed Scottish Land Fund. This was a watershed moment for Scottish land reform, in which feudal tenure was also finally abolished. (In England, by contrast, the process to end feudalism began in 1660 with the Tenures Abolition Act.) Yet on Bute, like in much of rural Scotland, there is little widespread desire for community buyouts. Far from progressive utopias, buyouts are sticky and tricky to achieve. They are often best suited to very small rural and island communities – Eigg, population eighty-seven, is the blueprint. While community buyouts make for compelling stories, they delegate to individual groups the impossible task of rebalancing the tipped scales of land ownership. At a micro level, there are many successes to celebrate, but at a macro level their scope is highly limited. Without a managed expropriation of post-feudal control of land, one in which landowners relinquish their control of farms, forests, and coastline so they can be run by and for the community, there is little prospect of rural communities across Scotland gaining greater access to the farms and market gardens through which they might grow food in an affordable and sustainable manner.

At the Anchor Tavern, Jenny O’Hagan, chair of the Port Bannatyne Development Trust, makes no effort to hide her pride as she tells the story of how the community got together to acquire the pub, rethreading an integral skein of community life in the town’s fabric. At the back of the pub is a community raised bed, run by Incredible Edible Bute. It is one of a number of free food-growing sites across the island set up by the charity Fyne Futures, which also runs Bute Produce, a six-acre market garden aiming to ‘grow the growers of the future’. Along with Bute Forest and the farms of Auchentirrie and Ascog, Bute Produce is one of only a handful of rural parts of the island not owned by either the MST or the Crichton-Stuarts, acquiring its site in 2020 after six years of protracted negotiation with the MST. The organisation employs locals with an interest in farming and horticulture, runs a successful veg box scheme, has an on-site kitchen, hosts cooking classes, and makes preserves and jams for sale. In making market gardening and locally grown food accessible, affordable, and part of community life, Bute Produce looks like the Good Food Nation Act in action.

While at Bute Yard, wandering around on a busy market day, or sitting outside in the sun eating tacos and enjoying a beer, I felt the cognitive dissonance at the heart of the project. While it creates a nexus for food and drink on the island, and takes some clear steps towards enacting a Good Food Nation, it does so via a Smithian invisible hand. Bute Yard is symbolic of the Crichton-Stuart’s benevolent work, but it also speaks to the refusal to address the underlying issues of poverty and inequality on the island. Recently, the MST has advertised a number of long-vacant units to rent in Bute Yard’s immediate vicinity. These include the Crichton-Stuarts’ unoccupied seventeenth-century, A-listed Mansion House property overlooking the ruins of Rothesay Castle. Meanwhile, one vendor at the market tells me they’re already worrying about the rent going up this summer, which they anticipate will push out some of the smaller vendors. For all its apparent altruism, Bute Yard seems to benefit the Crichton-Stuarts first, then its partner businesses, and only then does it consider the interests of small business owners, if they can afford the rent in the first place.

The Crichton-Stuarts might draw some inspiration from a member of their own clan, Ninian Stuart, who has begun to slowly transfer ownership of his Falkland Estate in Fife over to the community. It will be the first of its kind in Scotland, in which a landowner gradually divests his patrilineal inheritance to the community to steward the land themselves. Bute Produce and the Port Bannatyne Development Trust show that when land is more equitably managed, food can once more become a meaningful part of rural living, improving quality of life and fostering a sense of community. But without this also being coupled with greater land-acquisition powers, there is no route to land sovereignty, nor any meaningful ‘Good Food Nation’.

So aye, Bute Yard is pleasant enough. But what about that land of yours?

Note: This article has been updated with two factual corrections. 1) Cathleen Crichton-Stuart is the second daughter of Johnny Bute, not the first. 2) During the writing of this article, Cathleen Crichton-Stuart stepped down as a director of Bute Kitchen.

As stated originally in the piece, Bute Yard and the Mount Stuart Trust are separate entities. In response to the reporting in this article, a spokesperson for Bute Yard writes: “Bute Yard was set up to foster and to build economic growth in the local area, and is part of a number of projects helping to regenerate Rothesay and the island as a whole. Our focuses are local job creation, social accessibility, island repopulation and providing something positive and year-round that’s entirely new to the island.”

Toby Anstruther of the Mount Stuart Trust writes: “Since 2020, we have welcomed six new farming families to Bute on modern long-term tenancies and have been widely praised by the Scottish Land Commission and Scottish Ministers for creating a positive model of land ownership that benefits many. We were one of the very first charities – and remain the largest – to manage an Island for public good, preceding Eigg and Gigha by many years. We are also very proud that the approach adopted at Falkland was inspired by the model we pioneered. We believe strongly in the value of charity ownership for public good even while recognising that balancing competing demands is always challenging.”

Credits

Robbie Armstrong is a journalist, reporter and audio producer from Glasgow. You can find him on Twitter and Instagram.

Vittles is edited by Sharanya Deepak, Rebecca May Johnson, Jonathan Nunn, and Odhran O’Donoghue, and is copyedited by Sophie Whitehead.

Some names have been changed at the request of the source

Wow, thank you, Robbie. What an impassioned and well researched piece, eye-opening

Thanks Robbie / Jonathan for publishing the comment - I appreciate the openness. The piece raises some really important issues and it is great to have them aired. As always there is so much more to do. I hope we can continue the discussion. As the recent piece in the Guardian* showed the role of food in regeneration is not straightforward. Add to that challenges around land ownership and, distinctly, land use and there is a lot to get right (or wrong)! Thanks for raising the issues.

* https://www.theguardian.com/food/2024/mar/20/britains-bitter-bread-battle-what-a-5-sourdough-loaf-tells-us-about-health-wealth-and-class