The Nostalgia Trap

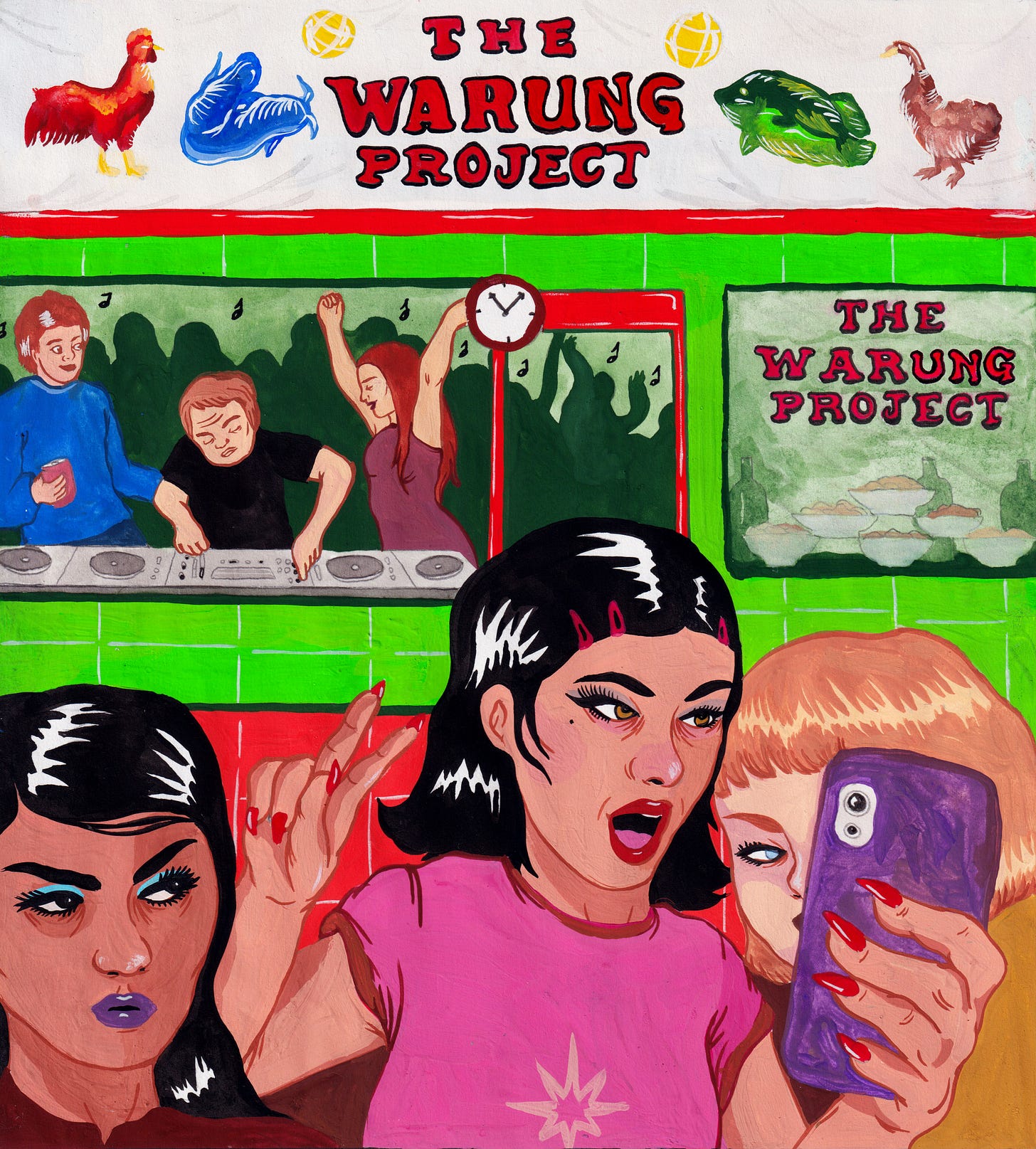

Why London's Southeast Asian restaurants are starting to look similar. Words by Rahel Stephanie. Illustration by Ula Zuhra.

Good morning, and welcome to Vittles! Today, Rahel Stephanie writes about the increasing use of nostalgic aesthetics to sell Southeast Asian cuisines in London, and reflects on her own complicity in doing so.

There are still a few copies of Issue 1 left - to buy it, please visit our website.

In Jakarta, warungs – small, working-class food stalls – are everywhere: on sidewalks, tucked behind markets, at the edge of residential alleyways. They are places where customers from all walks of life gather for affordable, satisfying meals, like soto ayam or pecel lele. Inside, you might catch a group of aunties gossiping over plates of hot food, savouring every bite while dissecting the latest scandal, like the neighbour’s son running away from his arranged marriage to a family friend’s widow. Next to them, a woman in a two-piece business suit might be seated across from a Gojek driver, or a bunch of punk rockers beside off-duty policemen. This is where the pulse of Indonesian food culture plays out. Informal and improvisational, warungs are for anyone and everyone – and whenever you need one, they’re there to have you.

Aside from the diverse clientele gathered around plates of hot food, you can spot a warung because of its banner: loud, plasticky, brash with colour. Bold fonts shout the names of the dishes on offer, and are often accompanied by cartoonish animal illustrations. Their design is functional, direct, and defiantly unstyled. But increasingly, warungs have become the inspiration for trendy contemporary restaurants that trade on a romanticised idea of eating on the street. Both in Jakarta (where I grew up) and London (where I now live), warung culture is deliberately imitated through art direction. I have seen food establishments that borrow the visual language of the warung, lifting, refining, and ultimately serving their signifiers as designed experience – from saturated banner fonts to fluorescent lighting, from plastic stools to melamine plates; I have even seen sambal-making parties, with guests invited to grind chilli paste to the beat of pop music. There are music videos shot in warungs and DJ sets in their gentrified incarnations – places where people dance among instant noodle stacks and plastic sachet garlands, reducing the everyday table to mere party setting.

I roll my eyes at this aesthetic merchandising – which is awkward, because I’m probably the poster girl. I once posted an algorithm-friendly thirst trap of myself using a stone mortar to grind spices. In hindsight, I wasn’t reclaiming the moment so much as performing it. Another time, I posed with a cup of instant noodles in front of a sachet-stacked warung – a backdrop so recognisably Indonesian it became the cover of an NTS show I recorded which explored music from the archipelago. At the time, it felt playful and rooted in affection. But looking back, I can’t ignore my own complicity in turning lived experience into something palatable for Western audiences.

These exercises (including my own) are a polished, streamlined version of culture, staged for approval. In Jakarta, this tendency to merchandise and glamourise food aesthetics reflects a romanticisation of the working class by the middle and upper classes. In London, the phenomenon is shaped more by a cultural tourism that thrives on stylisation and palatability. In both cases, authenticity is strategised not as a bridge to understanding a culture, but as a commodity to be styled and sold. From ‘elevated’ street-food joints to hyper-designed contemporary Southeast Asian restaurants, this merchandising – that relies on what I like to call ‘branded nostalgia’ – is everywhere.

In Southeast Asia, lining food with banana leaves and vendors who roam with modified bicycles or carts (kaki lima) are not aesthetic choices, but adaptations born of economic constraint and necessity. Yet, in different settings they become flattened to design language – punchy, photogenic, nostalgic. Consider Speedboat Bar in Soho, which riffs on Bangkok’s Chinatown, borrowing heavily from its visual language (but not before filtering it through the lens of what will pop best on Instagram). Think mint-green tiled walls, stainless steel tables, red vinyl chairs, plastic stools outside. When you enter the restaurant, there’s a backlit menu board in that fluorescent glow reminiscent of Southeast Asian hawker stalls, plus laminated menus propped upright like set pieces. The flooring is deliberately mismatched, the walls are crowded with framed memorabilia – old football shirts and photographs of Thai boatmen. It looks like someone built an AI model out of Thai street stalls and installed it in Soho.

When it opened in September 2022, I was invited to the launch, where a Thai singer performed in the background – an ambient presence rather than a featured voice, folded into the atmosphere. My plus one and I felt so uncomfortable we asked to be seated outside, witnessing the spectacle from a distance. Which was frustrating, because the food – pork crackling and cellophane noodles on retro floral and neon melamine plates; tom yam mama noodles in metal hot pots – wasn’t bad.

The chef behind Speedboat, Luke Farrell, has lived in Thailand for years. But while that proximity may inform his culinary approach, it doesn’t dissolve the power dynamics at play. That he is a white man isn’t insignificant – it’s often white men that are given the platform to interpret these cuisines, their proximity to a place presented as authority even when that interpretation remains extractive. And why is it so often Thailand – spicy enough to feel exciting, distant enough to be safely exotic, soft enough to absorb projection?

But of course, the commodification of culture isn’t limited to white chefs or restaurateurs. Groups like JKS, who back Speedboat Bar and other hyper-stylised ventures, aren’t white-owned, but they still operate within an industry shaped by what feels ‘discoverable’, what gets funded, and what kinds of stories are easiest to sell. The issue isn’t only who’s behind the project – it’s who the aesthetic is designed for, which specific Asian culture is moodboarded and sold to the predominantly white or affluent clientele.

I see these motifs everywhere now, recycled like aesthetic shorthand – not because they were drawn from my own background, but because they’ve become go-to signals for an airbrushed, exportable image, a broad idea of Southeast Asian ‘vibe’. For someone like me, who knows the reference points but feels uneasy watching them staged for theatre, recognition can be more alienating than invisibility; it says, I see you, but only the version of you that can be easily digested: a caricature. Even if not in a restaurant that serves Indonesian cuisine, witnessing these symbols of Southeast Asian food makes me think of how the food that I grew up with is vulnerable to aestheticisation and can be used as cultural shorthand in similar ways.

I have often felt the caricature being drawn around me: in interviews, my voice has been filtered through a lens that romanticises the Indonesian contexts I speak of, Bali in particular. My work has been framed through unnecessary, familiar tropes – ‘island of the gods’, spiritual mystique, lush beaches – because they flatter a Western gaze. The result is floral and distant, a version of Indonesia that erases the textures, tensions, and lived realities of Indonesians.

What makes branded nostalgia so effective as branding is that it panders to the consumer. Staged by developers, restaurateurs, and brand strategists, authenticity becomes a tool used to lure audiences seeking connection without complication. Le Bab, for example, frames its posh kebab as a reimagining, even an elevation. Lucky & Joy, a white-run Chinese-ish spot, once featured a dish called ‘Grandma’s Potatoes’ – a name that gestures toward heritage but never clarifies whose grandma, exactly1. It suggests a vague nostalgia, styled to resonate broadly without needing to explain itself. Instances like this are uncomfortable – cultural voyeurism that sanitises complexity. You get the flavour of someone else’s world, but not the histories, constraints, or lived realities that shaped it.

I have witnessed this in London’s curated food halls – places like Market Place Peckham, BOXPARK, or KERB Hackney Bridge. Unlike the bustling food courts or hawker centres of Southeast Asia, these venues are far removed from the everyday thrum they try to emulate. I grew up between Singapore and Jakarta, where hawker centres and warungs weren’t just places to eat, but lived social ecosystems. You’d see regulars holding court over kopi and kaya toast, stall owners gossiping across counters, uncles using tissue packets to save spaces at tables. There was a kind of public intimacy that cannot be fabricated outside its primary context. As TW Lim writes, hawker centres are not just culinary; they are civic spaces, rooted in policy, community, and working-class ingenuity. London’s food halls, by contrast, imitate the aesthetics but hollow out the structure, and what remains is architectural cosplay.

In all these cases, what is sold to enthusiastic diners as a ‘food experience’ is often built on shaky ground. These glossy new arrivals offer a vision of diversity, but one that rarely includes the voices of those whose cultures are being served. They are also constructed in parallel to East and Southeast Asian businesses being steadily edged out by rising rents and gentrification. In both Jakarta and London, what once served communities becomes spectacle, designed not for those who live it but for those passing through.

‘The thing you have always suspected about yourself the minute you become a tourist is true: A tourist is an ugly human being’, Jamaica Kincaid once wrote. Replace tourist with the diner of this piece, and the sentiment holds true. What gets called ‘authentic’ today is often performance, shaped not by those who live the culture but by those who stand to profit from staging it. The spaces don’t just sell food – they sell a mood, a memory, a moment. A ‘vibe’ that flatters the diner into thinking they’re connecting with culture, when really they’re connecting with the menu design – flavour borrowed to fill the void. I have found that my work – and by extension, the culture it represents – is only welcome if it can be tailored to fit these frameworks. This is conditional acceptance, where marginalised cultures are styled as cultural accessories but rarely permitted full authorship in the British – or global – food and restaurant industry.

So can a restaurant in London serve this kind of food without slipping into the same traps? Maybe – but only if it reckons with who its experience is designed for, the gaze it’s designed to meet. Because once a cuisine is introduced at a distance, it becomes easy to stylise, easier still to romanticise. Culture gets abstracted into ambience, even if not always deliberately or maliciously. Here is a reckoning for all of those who have tried to translate memory into image, identity into aesthetic. After all, to perform nostalgia is to perform and flatten ourselves – curated, legible, marketable. Maybe, then, the real work isn’t perfect representation, or a fidelity to the tradition in cuisines. It is also dismantling the habits – in restaurants, in media, and in ourselves – that made stylisation feel inevitable in the first place.

Credits

Rahel Stephanie is a London-based Indonesian chef, writer and presenter, known for Spoons, her acclaimed supper club spotlighting the depth of her home country’s cuisine. From sell-out events to a national Wagamama rollout, and features from the Financial Times to MasterChef UK, her work blends bold flavour with cultural intention and critical storytelling. You can find her on Instgram at @eatwithsp00ns

@linda_from_accounting.Ula Zuhra is a storyteller, illustrator, cartoonist and visual artworker based in Jakarta. In 2021, she co-founded Studio Cacing, an animation studio.

Her works include themes of feminism, class, eroticism, mythological and esoteric practices in Indonesia using a wide range of mediums such as painting, video, cartoon and sculpture. In 2024, Ula relased her first full length graphic novel titled Aca & Ica: Collected Stories under Bali-based Cahyati Press. You can find her on Instagram at @ulazuhra.The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

The photographs in this piece are by the author unless mentioned.

In response to this article, Lucky and Joy wrote to us to clarify that Grandma’s Potatoes “is a direct English translation of its Chinese name. It’s a delicious and well-loved staple from Yunnan province, and the name is widely used.” Lucky and Joy would also like to point out that it has recently refurbished the space to move away from the branded aesthetic described.

Very much in agreement but I would also say that this caracturing of cuisines happens not just in unfamiliar SE asian cuisines. For ex - the American diner 60s style cafe. Or even Balthazar both in nyc and london - a sophisticate curate of a french bistrot.

Maybe this is all to say that most people aren’t prepared to do deep dives into cultural and context. Instead they want stylized facsimiles.

I think the insight that this process of styling "flattens" the source culture, is very helpful as an analysis of all tourist promotion... Selling simplified image and concepts is the basis of all advertising and promotion, a selling out.