The Professor of the Lower Senses

Ruby Tandoh on Brillat-Savarin and the invention of modern food writing.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles. This month is the 200th anniversary of the death of Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, the French writer, gourmand and polymath who invented modern food writing. To mark it, we’re publishing a special long read by Ruby Tandoh on Brillat-Savarin, his work and his life, and why his writing remains important today.

Issue 2 of our print magazine, on the theme of Bad Food, is still available. You can order a copy below.

Just before lunchtime one October day in 1790, a man walked into a bar. Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin had left his home a couple of days before and travelled with his favourite horse northward through the Jura in east France. He had offended some revolutionaries, followers of Robespierre and Marat – he could be a little pompous. So he was on his way to the small town of Dole, where he was to meet a government representative to ask for a letter of safe conduct. They were the worst years of the French Revolution, but it was also game season, and this was wine country. Either he’d be sent to the scaffold, or he would not. First, he would dine.

And so, at lunchtime, Brillat-Savarin walked into the bar – well, a small provincial inn – and saw a spit threaded with tiny French quails. There were corn crakes, too, famed for the delicacy of their livers. Someone had laid a round of toast under the dripping birds. And the hare – the smell of it ‘would be enough incense for a cathedral’. You can imagine how he felt when the innkeeper told him that it all belonged to some lawyers celebrating an inheritance case, but that monsieur could, if he pleased, have some mutton and bouilli. Brillat-Savarin hated broth; he would later devote many words to this. He insisted on joining the strangers, and they, impressed by the audacity, let Brillat-Savarin sit with them. To the game they added truffled chicken fricassée, set creams, fruits and cheese. They drank and sang: he ad libbed a song about good company and feeling blessed and got a round of applause. When he went to Dole that evening, the government representative’s wife, Mme Prot – a pretty but emotionally neglected music lover with whom he spent the evening flirting – agreed to put in a good word.

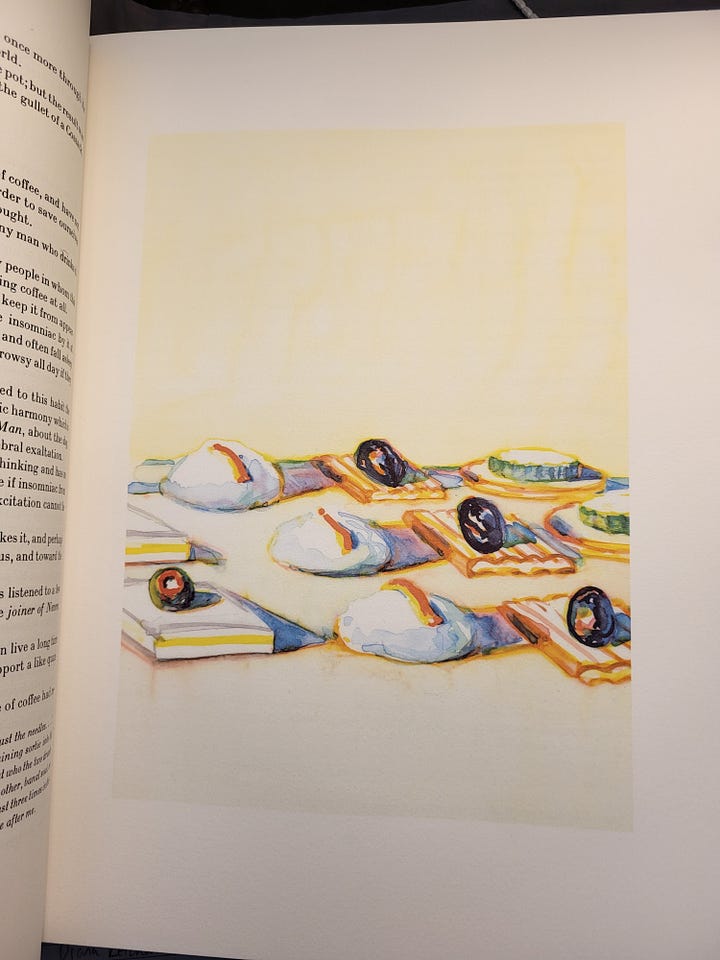

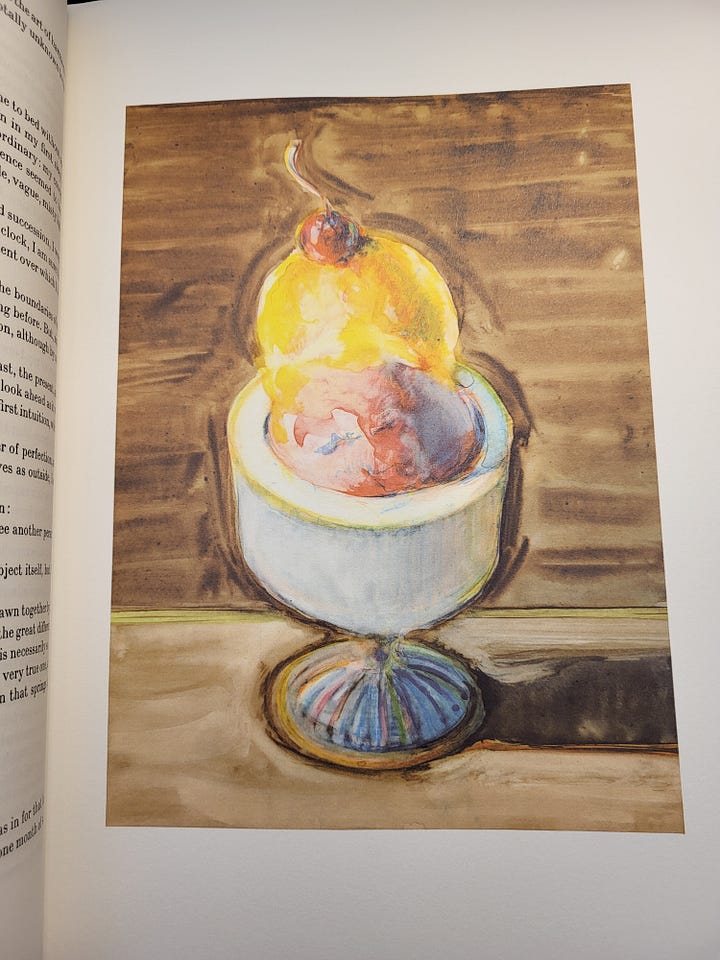

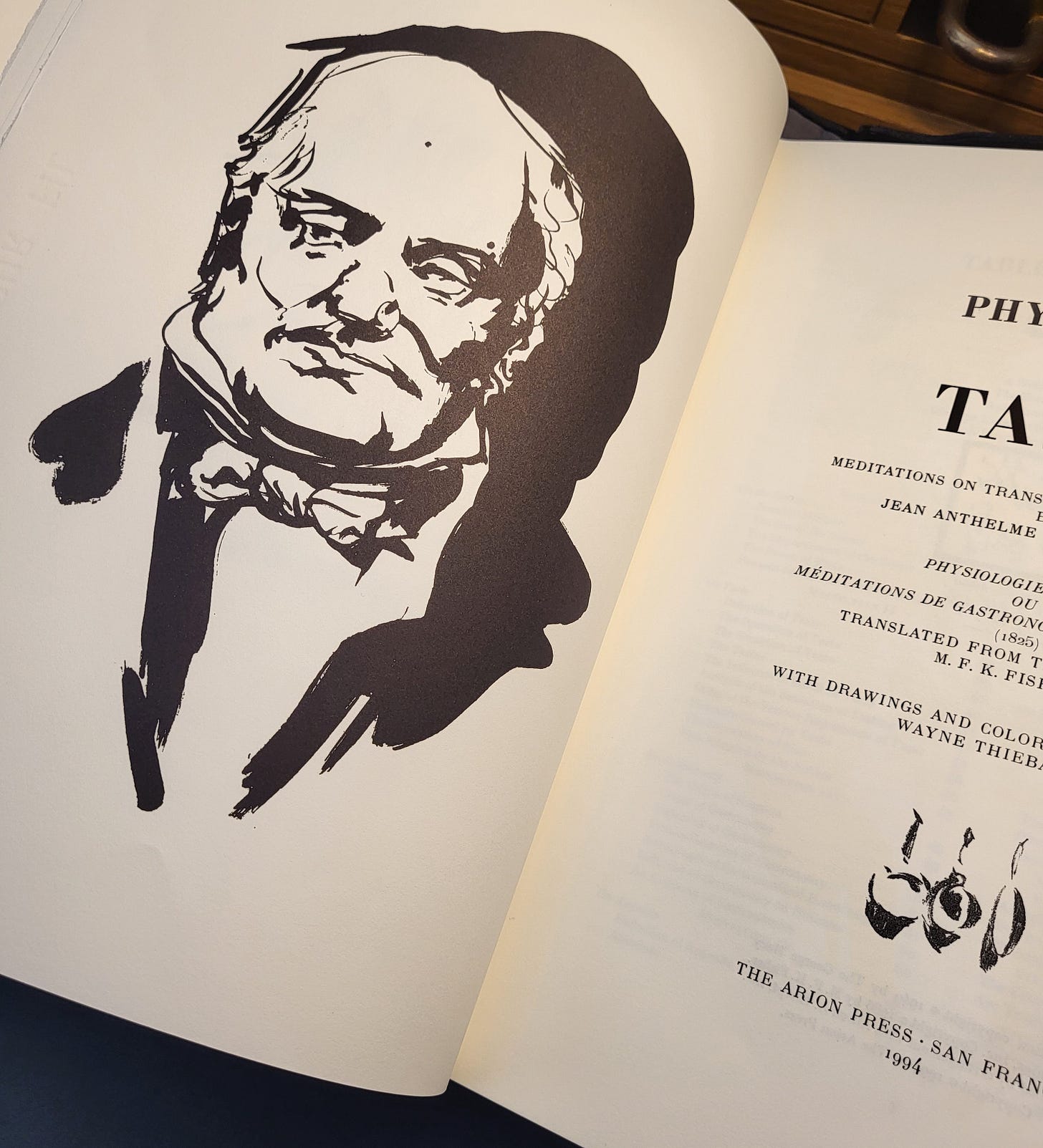

The note did what Brillat-Savarin needed it to do. It is how he lived to publish the story of the visit to the inn, in an essay of crystalline and somewhat self-flattering detail, in The Physiology of Taste. Today, anybody who knows of Brillat-Savarin knows him for this book, which was published in December 1825, a couple of months before his death. It is a catholic collection of aphorisms, essays and meditations on the nature of eating and, as things happen, the most influential non-recipe book ever written about food. It has been in print in France almost continuously for the last two hundred years, and has been available in English since 1854. Generations of food writers have built upon and disputed Brillat-Savarin’s work. For decades after The Physiology of Taste’s publication, literary types deferred to his judgement, the nineteenth-century version of ‘Well of course Nigel says…’ M.F.K. Fisher’s translation of the book – with its quibbling, with its digressionary footnotes and fond tellings-off – reads as a love letter to the man (she even goes so far as to say that he would have made a great husband, which shows how dazzled writers become in his presence). It would be impossible to enumerate Brillat-Savarin’s spawn: the food books and magazines, the essays and culinary memoirs, pieces of ostensible journalism and, today, across-the-dining-table podcasts. Saying that he influenced Western food writing doesn’t do it justice. He all but invented the genre. He is our Defoe.

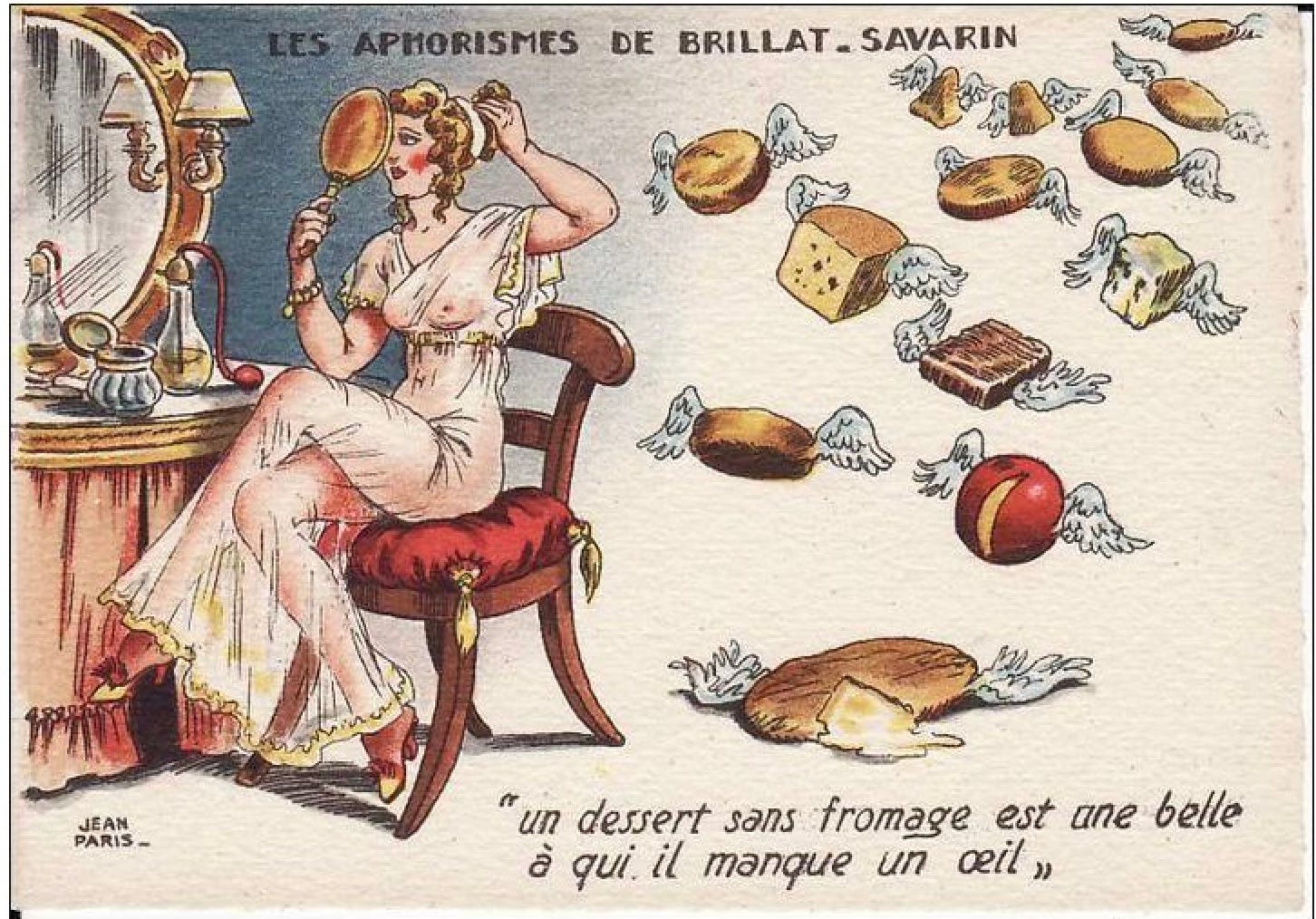

Like many people, I knew Brillat-Savarin’s quotes before I knew who wrote them. If you have spent any time at all reading about food for fun, you will probably have come across one. Some of the teachings are so generic as to be useless (‘The Universe is nothing without the things that live in it, and everything that lives, eats’). Others have proven as indecipherable as the ancient glyphs (‘We can learn to be cooks, but we must be born knowing how to roast’). But there is something about the Professor’s assuredness – it beguiles. Take: ‘A dinner which ends without cheese is like a beautiful woman with only one eye.’ Or: ‘The discovery of a new dish does more for human happiness than the discovery of a star.’ This one has been quoted so many times that it is practically the lorem ipsum of cookbook epigraphs, although Brillat-Savarin didn’t even come up with it. As generations of writers have done since, he stole it – in his case, from a judge he knew.

The most famous aphorism, perhaps the most over-quoted sentence in the history of food, is the fourth: ‘Dis-moi ce que tu manges, je te dirai ce que tu es’, or, ‘Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.’ We have gradually perverted the original phrase to ‘You are what you eat’. I have done it myself, grasping towards something ontological about what eating does to us, turning it into a causal thing and totally missing that Brillat-Savarin’s original is dialogic. ‘Tell me what you eat.’ Half of Brillat-Savarin’s aphorisms are about dinner party etiquette – what to do about late-running guests, or the order in which to bring out drinks; they could have come from Martha Stewart. This is table talk.

We have taken Brillat-Savarin so very seriously that, the more we revere him, the less we really understand. In fact, it is gut-wrenching to think just how much bad food writing could have been averted if people had only read beyond the first two pages of his book. The real Brillat-Savarin lives in the couple of hundred meandering, heavily anecdotal pages that follow the aphorisms – the stories like the one in the inn, where you find him suddenly in the room, a tiresome but unignorable old uncle who can take a sharp left through a tale from his war stories and end up on the topic of a chicken he once ate. This is the good stuff. It is here, a shade over two hundred years ago, that Brillat-Savarin had a deceptively seismic idea, one that we’re still reckoning with today: that it might be as enjoyable to discuss food as to eat it.

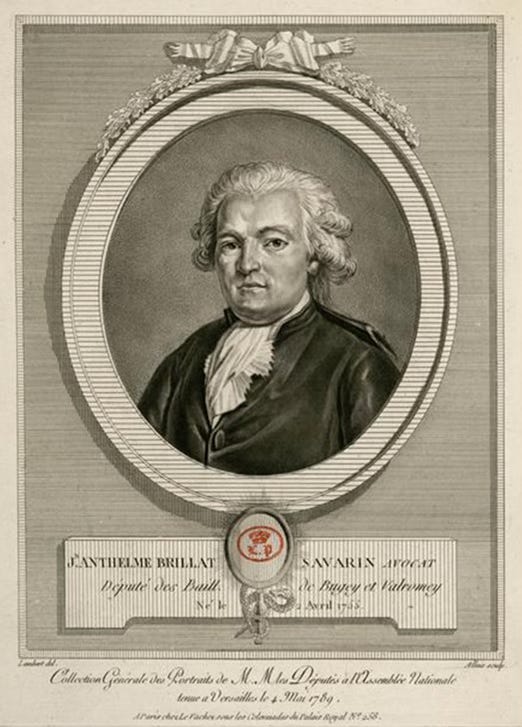

Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin was born in 1755, the eldest son of wealthy parents, in the small cathedral town of Belley. The family passed the legal trade down through generations of first-born sons, locals said, the way that kings beget dauphins. He became a magistrate, then joined the National Constituent Assembly in 1789. From the papers he has left us, it seems his hope was for life in France to be – bar the adjustment of a few seasonings – as it always had been. He wrote against the division of his France into bureaucratic départments, the butchering of the patrie. He scoffed at the idea of trial by jury. He appears to have defended the death penalty with more verve than he represented his own clients, who found him boorish. He was tall. Balzac, who admired him, described him as the ‘drum major of the court of cassation’. He had his virtues, if he must say so himself. ‘Although I carry around with me a fairly prominent stomach, I still have well-formed lower legs, and calves as sinewy as the muscles of an Arabian steed.’

When he wasn’t working, Brillat-Savarin played violin. He researched pet topics like languages and the art of duels. Most of all, he dined. Bugey, the prefecture where you will find Belley, was famed for its food. ‘Crayfish, trout, and pike abound in our rivers,’ Belley local Lucien Tendret wrote in La Table au Pays de Brillat-Savarin. ‘There is a profusion of truffles, morels, and mushrooms in our woods.’ The locals had a right to brag. Have you ever had écrevisses, served under a sauce made of butter infused with crayfish tails and shells, and béchamel? You could get leverets in that country that Parisians could only dream of. The river Furens, M.F.K. Fisher later wrote, had rose-fleshed trout and pike ‘as white as ivory’. The signature dish of Brillat-Savarin’s mother, Claudine-Aurore, was a pillow of liver paté that they called oreiller de la Belle Aurore. This is the terroir that produced Brillat-Savarin.

In late October 1790, with his letter of safe conduct, Brillat-Savarin returned to Belley. For a while he went back to his duties. They even made him mayor, but things weren’t the same. He belonged to a pre-revolutionary France and never truly got over its loss. In December of 1793, a couple of months after they beheaded Marie Antoinette, he fled eastward, crossing the border into Switzerland. It was during his years in exile that Brillat-Savarin collected many of his finest anecdotes. In Lausanne, there was the man who only ate twice a week; Brillat-Savarin invited him to dinner out of pity. Never again – ‘I shuddered to watch him gorge.’ He heard a story in Cologne about a Frenchman who grew rich by making salad dressings and carried a mahogany case of vinegars, truffles, anchovies, ketchup, oils and caviar. It’s a charm of Brillat-Savarin that he gives no preferential treatment to the things he saw himself.

Brillat-Savarin arrived in the United States in 1794 and spent two years in aimless peace. These were the years when he had his enlightenment: that there is much to be gained, even in the mundane things in life, by simply paying attention. In Hartford, Connecticut, he went out hunting and saw, for the first time in his life, virgin forest, ‘where the sound of an axe had never been heard’. The New World. When he finally shot a turkey, he sat with it for an age, just staring. In New York, he made note of where to get the best ice cream and who went there, and when, and what they bought. He must have been there for hours, watching the women with their ices. Hamstrung by his English, he talked less at the table and listened more.

This is just one of Brillat-Savarin’s many surprises – that it was away from France, far from the heartland, that he perfected his gastronomy. Before his exile, Brillat-Savarin had written a couple of political essays and some erotica (Brillat-Savarin scholars mourn the loss of these contes, which his inheritors destroyed). But he never wrote about food, and why would he? The feast was certain to be there tomorrow, and the day after that. Exile forbade his complacency. He made a science of noticing, then of recording and theorising every seemingly mundane meal. ‘I soon saw, as I considered every aspect of the pleasures of the table, that something better than a cook book should be written about them.’ Better than a cook book – we’re still dealing with the ramifications of this one rogue idea. It is the idea that thinking about food might be worth more, somehow, than simply making and eating it. That reading about food might be a pleasure in itself. It was around this time that he started writing The Physiology of Taste.

It is hard to imagine The Physiology of Taste being published today. If it feels as though Brillat-Savarin simply collected every digressionary thought he ever had about food and printed them, unedited, in a book, it is because this is what he did. Publishers turned it down, so he self-published for a readership of his friends. We should be thankful for this. It’s because nobody edited him that The Physiology of Taste is an accidental self-portrait. The prose bulges when he is intrigued, and slims to the barest sentences when he is bored. To say that it is idiosyncratic is shirking its full weirdness. There is a chapter about the end of the world, and others about sleepwalking and death. Brillat-Savarin gets the topic of restaurants out of the way in a few paragraphs, but gives many, many pages to the charms of women.

Brillat-Savarin loved women. In fact, it is difficult to think of anyone from the last two centuries of profoundly horny literary men who has loved them more. ‘I see every day such wenches,’ he wrote about American women in his letters, ‘with marble-hard and snow-white breasts on which I gaze panting to kiss.’ His English grew ragged with excitement. ‘I am sure that the future time is big with good slaps.’ Of shooting lunches, he wrote: ‘At the appointed hour light carriages arrive and prancing steeds, bearing beautiful ladies, plumes and flowers. I have seen them spread out on the grass turkey in transparent jelly, home-made pâté, and salad ready for mixing. I have seen them dance light-footed around the camp fire.’ He fell in love with Herminie de Borose, his friend’s daughter, with chestnut hair and nymph-like carriage, whose feet were some of the shapeliest he ever saw. At some point he talked her into giving him her small black satin shoe, and kept it for the rest of his life. All of this went in the book.

It would be a mistake to see these as digressions. Brillat-Savarin was a philosopher of desire. To the five senses we already know, he added a sixth: horniness. No, really – ‘Let us grant to physical desire that sensual position which cannot be denied it.’ He theorised. Sight and sound help us know our place in the world, touch helps us manipulate the things that surround us. With smell and taste, we interrogate these things to learn if they are good. We eat. ‘And now a strange languor invades the body,’ he wrote. ‘A secret fire is aflame in his breast; he feels an urge to share his existence with another being.’

Of all the special interests that made it into his book, it was physiology that most excited Brillat-Savarin. It is the foundation of so many of his follies (one of the best things that ever happened to him was being mistaken for a medical doctor one time). He frittered his time away, doing things like coming up with a prototype of what we would now recognise as an Air Wick diffuser, and coming up with a name for it – the irrorator. (He often found the French language inadequate for the grandeur of his thoughts.) Brillat-Savarin was raised with the hubris of the Enlightenment – we have to give him the grace of remembering that. His age mate is Diderot’s Encyclopédie. He grew up with all that expansive humanist thought at just about the last point in Western history when people still believed that existence could be understood, even mastered, by individual, brilliant men. To the armchair essais of philosophers like Michael de Montaigne, he added rigour. ‘I needed to be doctor, chemist, physiologist, and even’ – not that he liked to dwell on it – ‘something of a scholar.’

He made a great many observations: ‘Some people are cantankerous as long as they are digesting: this is not the time either to propose new projects or to ask favors of them.’ Brillat-Savarin was one of the first writers to advocate for low-carb diets. He got a lot of his medical expertise from his godson, the surgeon Anthelme Richerand. It was from Richerand’s popular but critically denounced Nouveaux Élémens de Physiologie that Brillat-Savarin took many of his theories, some of them almost word for word. It’s extraordinary, in fact, just how Brillat-Savarin looked up to Richerand – a man twenty-four years his junior who was known for how, ‘with pathological envy and hatred, he pursued those, alive or dead, who, in his mind, obscured his fame.’ But Richerand never did turn on his greatest plagiarist. The two seem to have realised early that the second-rate scientist needs the first-rate writer, and vice versa, simpatico.

Few besides Brillat-Savarin write with such vivid precision about the body. The tongue ‘endowed as it is with a certain amount of muscular energy … serves to crush, revolve, compress and swallow.’ He explains how ‘the cheeks furnish saliva’.He is the only writer I have known to make a David Attenborough-style thriller of the act of chewing. ‘As soon as an esculent substance is introduced into the mouth, it is confiscated, gas and juice, beyond recall,’ he writes. ‘The lips cut off its retreat; the teeth seize and crush it; it is soaked with saliva; the tongue kneads it and turns it over; an intake of breath pushes it towards the gullet … and down it plunges. Not one particle, not one drop, not one atom has escaped the attention of the apparatus of taste.’ You can feel him quivering with the exertion of setting the record straight, 185 years after Descartes’ Meditations, trying to break down the idea that cognition is the most important thing we do as humans. Look at the lower senses, Brillat-Savarin said. This is where we find ourselves.

In 1800, Brillat-Savarin moved to Paris, where – except for summers in Belley – he would spend the rest of his life. It was there, in December 1825, that he anonymously self-published The Physiology of Taste. It was typical of him – a lifetime of sermonising, then he put it all in the name of ‘The Professor’. There always was a defensiveness about his love of food: his knowing pompousness, his alter-ego, as if preparing for the day when he would reveal it was a joke. If he was worried that his colleagues, serious men of the bench, would grouse about it, he was right. What kind of a world was this, they complained, in which judges could act like clowns? But in Paris society, The Physiology of Taste was an immediate success.

It was a good time and place to be a gourmand. Some of the first modern restaurants were opened in the late eighteenth century; within a couple of decades, there was an entire Parisian dining scene. Alexandre-Balthazar-Laurent Grimod de La Reynière was the original restaurant critic. Marie-Antoine Carême, one-time chef to Tsar Alexander I, codified French cuisine at a time when French wasn’t even a first language for most of its people and cooking tended to be regional. The lore was being written. There is no trace of the word ‘gastronomy’ in print until 1801, when it springs up in the satirical poem ‘La Gastronomie’ by Joseph Berchoux (it is one of those words – like gourmet, gourmand, gloutonnerie – that the French have invented at intervals to get at the social distinctions that fall under the unworkably broad umbrella of ‘eating’). The academic Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson notes that, at this time, ‘French cuisine became French not so much from the food eaten as through the texts written and then avidly read.’ A foodie, even now, isn’t someone who eats good food, but someone who talks about it.

The Physiology of Taste, with its subtitle Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy, was dedicated to this entirely new social tribe – ‘the gastronomes of Paris’. ‘Gastronomy is the intelligent knowledge of whatever concerns man’s nourishment,’ Brillat-Savarin wrote. It belongs to physics and chemistry, to vintners and hunters, to cookery and business, to merchants and bakers. ‘It rules our whole life. It also concerns every state of society.’ When Brillat-Savarin ran tests comparing what happens when you mill coffee beans versus when the beans are pounded, he would segue into the origins of coffee cultivation, then explain the impact of caffeine on the brain. ‘Voltaire and Buffon drank a great deal of coffee,’ he notes. And look what it did for them: ‘Admirable clarity’, ‘enthusiastic harmony’, ‘extraordinary cerebral exultation’. Then, at the moment he might be about to overreach, he brings it back with an anecdote. He was so good. A few years later, Balzac, who wrote Brillat-Savarin’s posthumous entry in the Biographie Universelle, wrote his own essay about coffee. Read it. It makes Brillat-Savarin look like Dumas.

Of all the hats Brillat-Savarin wore – and he was, by his own reckoning, something of a polymath – it is his sociology that most astonishes. A beat-by-beat of the time that Talleyrand showed up to his own dinner five hours late. The time he went to the pub and was told there was no meat, even though there was clearly a leg of mutton on the spit. Individually, they are sketches in the Curb Your Enthusiasm vein. But taken together, they record the social life of France at a time of revolutionary change. In Paris, he saw that the new gourmands were not the old aristocracy, but bankers, writers and clergymen. There were whole classes of people for whom food discourse was suddenly a thing. You could take gastronomy seriously. You could dine with Napoléon. Dis-moi ce que tu manges, je te dirai ce que tu es. We always get this wrong, mix up our pronouns. It is: Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are. Not the tender, personal who – the who of memoir – but what. What are you, in this strange new world?

If anything is testament to Brillat-Savarin’s talent as a storyteller, it is that nobody, least of all the people who knew him personally, could believe he wrote The Physiology of Taste. ‘His book alone revealed the sharp and profound wit of his mind,’ one wrote. ‘His conversation betrayed nothing of it; it was even short, indifferent, and monotonous.’ People said he ate ‘copiously but badly’. Friends noticed his old-fashioned clothes – all those frills, right up to the jowls. They said he almost never invited anyone round to dinner, and even if he had, who would come? He was barely known outside of the circles of his cousin, the society belle Juliet Récamier. (This much may be true – he was in love with Récamier and even had a bust of her in his house.) But when he is mentioned in her letters it is only once, as ‘the magistrate’. Even those who truly liked him didn’t know what he was capable of. ‘For them,’ his friend Richerand wrote, ‘Brillat was just a nice man.’

Less than a month after The Physiology of Taste was published, Brillat-Savarin caught a cold at mass. On 2 February 1826, he died of pneumonia. He never got a chance to enjoy the book’s success, although that might not have been the worst of his losses. The autumn before he died he had been picking Côte-Grêle grapes down near Belley: ‘making my wine by a new method of my invention’. He was excited enough to write to his friends about it. ‘I think it will be just right in March.’ This is the thing in all Brillat-Savarin’s work that cannot be argued with: his joy; this ability, right until the very end, to encounter every food as if for the very first time. He believed that pleasure was worth writing about. It is this – rather than his more quotable philosophising – that we would do well to remember. He invented modern food writing by insisting that nothing meaningful can be said about food without also speaking about how it makes us feel.

Montaigne, the other of France’s great thinkers about feeling, said it too. ‘I hate that we should be enjoined to have our minds in the clouds, when our bodies are at table,’ he wrote. ‘I would have the mind take its place there, and sit.’ Montaigne was a couple of centuries ahead of his time – he lived in a France before restaurants, before the discourse got its legs. Writers needed Brillat-Savarin to remind them of this once they were ready to hear it. He has been reminding us of it ever since.

Credits

Ruby Tandoh is a food and culture writer who has written about food, art, architecture and culture for Vittles, The New Yorker, The Baffler, Eater, Art Review, RA Magazine, Tate etc., The Guardian and more. Her new book, All Consuming, was released in September 2025.

The Vittles masthead can be viewed here.

Unexpectedly hilarious, and one of the best things Vittles has ever published.