The Story of Soupe Phnom Penh

How the popularity of one noodle soup in the 77 tells a story of Paris's east and south-east Asian immigrants. Words and photos by Wendy Huynh.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles. For the next two weeks, we will be sending out individual articles from our supplement Vittles Paris. To read the rest of the series, please click below:

The Vittles Alternative Guide to Paris

Rungis: The Market and the City, by Justinien Tribillon

The Last Critic in Paris, by Vadim Poulet

‘Welfare is a right, not a privilege’, by Jack Franco

Pourquoi pas?, by Jonathan NunnArticles from Vittles Paris are paywalled — to view them, you can subscribe to Vittles for £7/month or £59/year. Your subscriptions help pay all our writers, photographers and illustrators at a fair rate.

From time to time, I come across someone else of Asian heritage from a different part of the world who has a family member living in Lognes, one of the eastern suburbs of Paris that makes up the area known as the 77. When I do, I can bet that they are also immigrants of Chinese-Vietnamese heritage who arrived in Paris following the Vietnam War in the late 70s. Like me, they would also remember the park and lake by the station, waiting endlessly for their parents in the carpark of the Asian supermarket Tang Frères, and chaotic family gatherings at the local Chinese and Vietnamese restaurants.

As a child of Lognes, I have a love/hate relationship with the Parisian suburbs. I hated being far from the cultural centre of the city and feeling dismissed. But in the last 10 years, while living in London, I have come to lean on those memories of the 77: the Sunday Chinese classes in Noisiel with the teacher whose breath smelled like tangerines; seeing my aunt making tong yuen in her kitchen in Lognes; giggling under the dining table with my cousin while being told off for knocking the nước mắm on to the carpet.

One of the things I miss most about the 77 is a dish that I cannot find in London, and that has no special resonance for most Parisians: a noodle soup called soupe Phnom Penh, named after the Cambodian capital. In my opinion, soupe Phnom Penh is best served in the 77, but getting Parisians to travel to the suburbs for any reason is difficult, let alone for noodle soup.

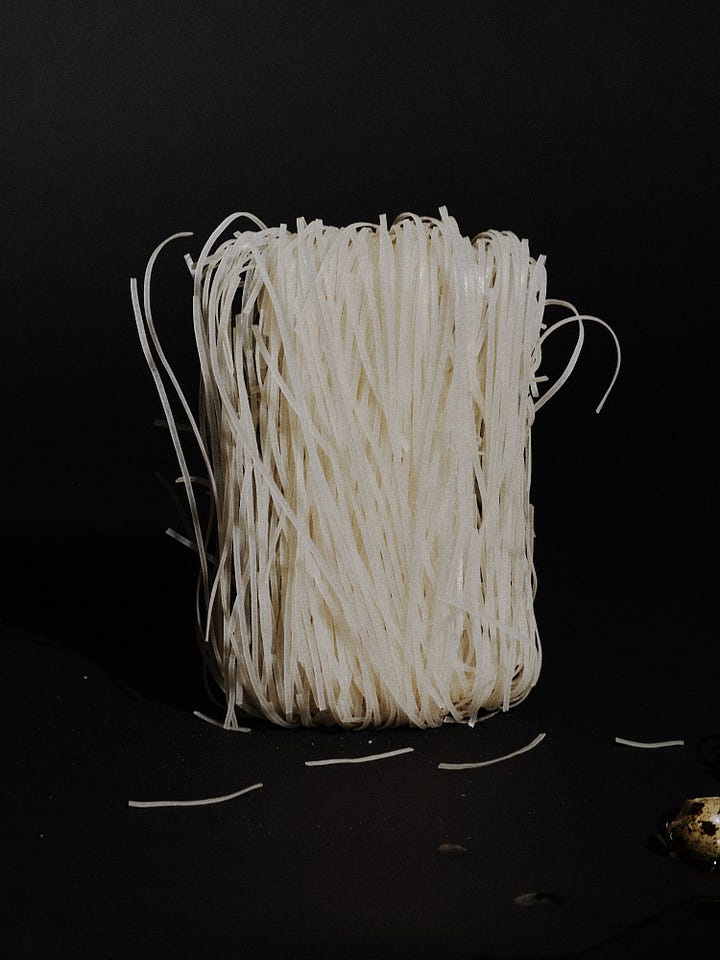

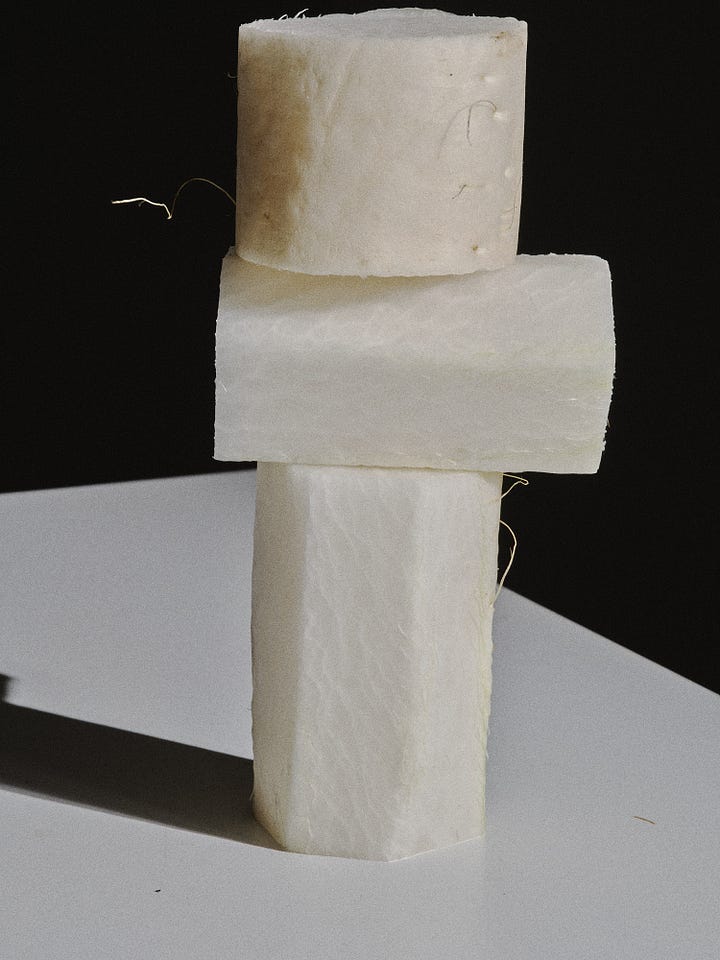

Soupe Phnom Penh can be eaten with the noodles mixed in the soup, or ‘dry’ – meaning the noodles and broth are served separately. The latter is my favourite way: the noodles are mixed with a sweet and savoury soy sauce and sesame oil, while the broth is made from reducing pork bones, dried shrimp and squid; if the noodles are too dry, you can add a spoonful or two of soup. What I love most is the process of finding the toppings mixed in with the noodles: sliced cooked pork, pork liver, sautéed ground pork, pork sausage, prawns and squid. On some lucky days, – depending on the restaurant and the chef’s mood – the soup might be served with a pork bone that still has some juicy, tender meat on it.

My favourite place to eat soupe Phnom Penh is Café de Lognes, a small restaurant tucked away in the back of a tabac. My family and I have been going here for more than 15 years, and now that I’m away from it I realise that, really, what I loved most about the soup is the ritual it became. Going for soupe Phnom Penh meant going for a meal out, an occasion to connect with my parents and siblings.

A few years ago, I asked a Chinese-Cambodian friend from Paris if her mum cooked soupe Phnom Penh, and she told me she didn’t know about it. It left me wondering whether I was calling it by its right name, or whether it even is a Cambodian dish. I asked my parents about it, and got even more confused about its origins.

“It’s the Chinese in Vietnam who used to eat this.”

“We didn’t eat this growing up in Saigon, it was not a thing.”

“It’s the Cambodians who came to Vietnam who used to sell this.”

“Actually, the first time we had this soup was in France, it was not a thing in Vietnam.”

They also told me to fact-check everything they were saying, as clearly they didn’t really know.

What they could tell me with certainty was that the first place they had the soup was the Tricotin, a restaurant in the 13th arrondissement of Paris. Back in the late 70s, that’s where you would find the whole of the Teochew community, when immigrants from south-east Asia came to Paris. According to my parents, the Tricotin was probably one of the first places in Paris to serve the soup.

After some sleuthing, I came to an answer of sorts: the soup originated from the Chinese diaspora in Cambodia – more precisely, from the Teochew people of the Guangdong province in China, who later emigrated to Vietnam, and then to France. The soup is actually called called Hủ Tiếu Nam Vang in Vietnamese, and Kuy Teav in Cambodian. People often say ‘You are what you eat’, but I didn’t realise how closely the story of the soup mirrors my family’s migration story. My ancestors, including my grandparents, came from Shantou in Guangdong, then emigrated to Saigon in Vietnam, where my parents were born and grew up. After the fall of Saigon, in the late 70s, my parents came to Paris. It was behind the Tricotin, near the high towers of Les Olympiades, that my mother was reunited with her own mother, sister and brothers. I could not believe that, after almost 30 years of eating soupe Phnom Penh, I had never understood the historical and migratory story it carried.

The soup is Teochew, just like my family and me. And like us, it is a dish that has moved from the 13th arrondissement to the suburbs of the 77. Soupe Phnom Penh has followed me throughout every stage of my life so far – in moments of celebration, in moments of grief, in solitude and daily routine. I imagine the soup thriving in the Chinatown of Saigon, and then with those who took the chance and the risk of travelling to France. Some by air, some by water. With those who made it, and those who didn’t.

Credits

Wendy Huynh is a French photographer based between London and Paris. Her work uses portraiture, documentary, and fashion to explore contemporary representations of identity, culture and place. She is the founder of Arcades Magazine, which focuses on the culture and lifestyle of the suburbs with each issue dedicated to a specific city’s suburb. As part of the ESEA community, Wendy uses her work to celebrate her community and raise awareness of its stigmatisation. You can find her on Instagram.

This supplement was subedited by Tom Hughes and Liz Tray. The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

I love this story. How food, history, heritage and family are so interwoven and important to pay attention to.

Très intéressant, j’habitais à Paris et je confirme