‘Welfare is a right, not a privilege’

Eating at the university canteens of Paris. Words and photos by Jack Franco.

Good morning and welcome to Vittles. Today’s article by Jack Franco is from our supplement Vittles Paris. To read the rest of the series, please click below:

The Vittles Alternative Guide to Paris

Rungis: The Market and the City, by Justinien Tribillon

The Last Critic in Paris, by Vadim Poulet

The Story of Soupe Phnom Penh, by Wendy Huynh

Pourquoi pas?, by Jonathan NunnTo read the entire series, you can subscribe to Vittles for £7/month or £59/year. Your subscriptions help pay all our writers, photographers and illustrators at a fair rate.

La restauration collective, or collective catering, is a special source of culinary pride in a land with no shortage of it. In France, canteen trade bodies run annual competitions that award chefs in large institutions, such as care homes, schools and hospitals, who source ingredients locally and sustainably, and turn them into healthy, cheap and flavoursome meals. No canteens represent this tradition in the French collective imagination more than the restaurants universitaires, or Resto Us. These are the 500 university canteens run by the Centre Régional d’Œuvres Universitaires et Scolaires, or Crous, a mammoth governmental body that plays a major role in students’ lives. Today, Paris alone counts around 20 restaurants universitaires, which are vital for the city’s student population of over half a million; although tuition is virtually free for many students in France, financial support is less generous, leaving a lot of students precarious when it comes to food. At a restaurant universitaire, a healthy, varied meal costs €6.60, but the state subsidises it by half, meaning €3.30 gets students bread, a salad or entrée, a generous main and a dessert. Students with a bursary pay a symbolic single euro.

Since I moved two years ago from London to study, I’ve started to appreciate the city through the menus of its canteens. Having grown up in the UK, I admire the restaurants universitaires for their idealistic yet utilitarian spirit: serving the greatest number of people as well as possible, while building creativity into the formulaic. You order according to a French-style, points-based buffet system; a total of six points is available – four for a main, one for sides and desserts, with every point over six accruing a 50¢ surcharge. Though the French might characterise the food as perfectly run-of-the-mill, to an outsider the selection of dishes can serve as an introduction to the cooking of the wider Francophone world. It was in a Lyon canteen that I discovered fish quenelles before I’d set foot in a bouchon, and tried a sausage rougail stew from Réunion Island, a creole cuisine so often omitted from France’s gastronomic story.

Wanting to see how the city’s restaurants universitaires change from area to area, depending on where and who they’re serving, I decided to keep a diary over a four-day week in spring detailing meals at canteens in different parts of the city. Although their existence highlights societal gaps caused by increasing inequality, the restaurants universitaires also represent necessary and feasible remedies to food insecurity and a growing lack of truly public spaces. These canteens stand for the idea that welfare – or in its literal French equivalent, bien-être, or well-being – is a right, not a privilege.

Day One: Restaurant Universitaire Mabillon, Rue Mabillon, 6th arrondissement

Menu du jour: red cabbage, cucumber and potato salad bowl – chicken yassa, spinach and rice – cherry crumble

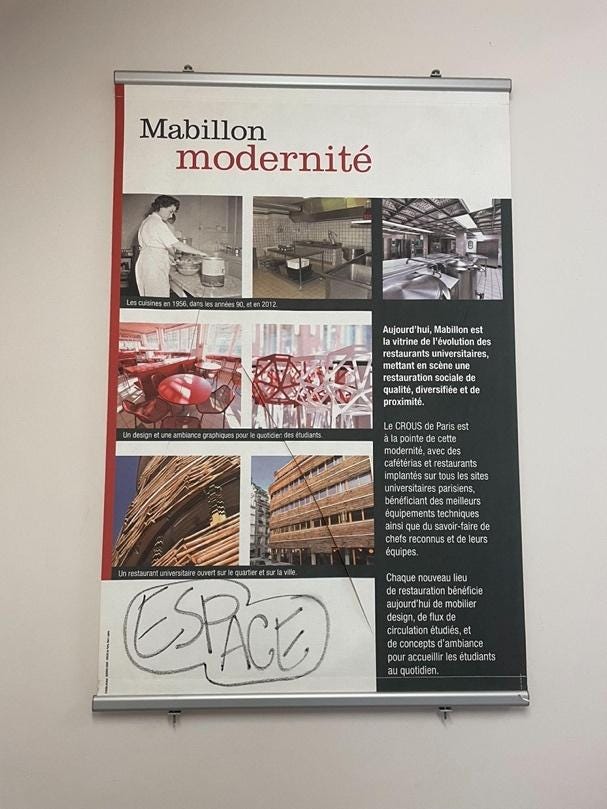

The 6th arrondissement is postcard Paris: the Senate, Jardin du Luxembourg and overpriced cafes living off long-dead reputations. It also has the Restaurant Universitaire Mabillon, the oldest university canteen in France. Founded in 1952, Mabillon is the Crous’ most emblematic canteen, spread across three floors and 660 seats. During the 1960s, it served 5,000 meals a day; though more canteens have since opened nearby, more than 1,600 meals still come out of Mabillon’s kitchen daily. Today, my tangy poulet yassa has let the onions do the work, as it should, although it’s a shame it has to share a plate with two ounces of overcooked spinach.

Mabillon is unmissable for one reason above all: its looks. As a small display case in the cafe dedicated to Crous history informs me, ‘Mabillon represents the nouvelle image of university catering’. On each of the three floors, strip mirrors line the walls. If you sit on one of the red wire chairs, your mate can take the diner-style couches in red leather. Soft light from the linear wall lights complements an already luminous place. This is one place where I prefer to eat alone, where I can look outside, peering over the tiled roof of the redeveloped market to catch a glimpse of Saint-Sulpice’s bell tower and apse.

Welfare in France is to feel the right to certain things, which includes the right to a thoughtful, enriching meal, set against a charming view, for a cheap price. Though not as ambitious as the Maoists in the 1960s calling for a student wage, there are still those, notably from leftist party France Unbowed, who are campaigning to recognise study as labour. One demand made by the party is for all canteen meals to be charged at the flat, symbolic €1 price currently reserved for students on means-tested bursaries – a policy that fell short by a single vote in 2023. The breadth of support for this idea – from the socialist left to the far right – is remarkable, but there is opposition from centrists and conservatives, who treat the Crous as another unsustainable treat for a swollen and predominantly middle-class student population. During my first stay in France in 2021, the €1 meal was implemented as a national Covid measure. What students eat and how much they pay affects how they study. After a meal in the Resto U, I am a well-oiled machine.

Day Two: Campus Condorcet, Aubervilliers, Seine-Saint-Denis

Menu du jour: brie & bread – honey and rosemary turkey, green beans, carrot duo – yoghurt

Since 2018, the mammoth Campus Condorcet has brought 11 universities’ social sciences departments and 50 libraries into one shiny, €600m development, a stone’s throw away from the Stade de France north of Paris. The historically industrial and immigrant area of Aubervilliers has been clinically redrawn: the relics of warehouses and terraced housing surrounding the Campus are scheduled for demolition. But it also houses what I think is Paris’s best restaurant universitaire. A friend describes it as the ‘gourmet’ branch, with slightly more variation and creativity in the menu than other Crous canteens. All my favourite meals last year were here: a plate of butternut squash rice and baked salmon for lunch one day, duck leg and chips for Christmas dinner. Today, the main – honey and rosemary turkey – is delicious, despite my apprehension about eating turkey at any time of the year. The honey and rosemary sauce seeps among the yellow and orange carrots. A sprig of rosemary, curiously unbroken, sits atop my serving.

As the menu changes from day to day, lunch often includes a moment of suspense. Yenifer, a Colombian master’s student, tells me: ‘This is probably the best canteen I go to, but it’s cool to try something new in each one. When I did an internship in Bayonne, I got to try Basque cooking.’ She sings the praises of the Basque city’s veal axoa, while recognising that the reliable culinary offer of the Crous often papers over structural cracks such as insecure student housing, the high cost of living and underinvestment in higher education. She promises to send me pictures she had enthusiastically taken of her Basque meal.

L overhears us and gets involved. A history student from the south of France, he laments the lack of creativity in the canteens’ veggie menus. He thinks many students learn what they like to eat from the canteen, and then try to cook it. ‘If all we see is pasta with chickpea stew, we’ll get lazy and end up not eating properly,’ he tells me. He’s right, and by the same token, canteens can show us how to cook well, and thoughtfully, too. Some of the cooks bring personal recipes, Francophone or otherwise. I was intrigued when I saw arroz com amêndoas on the menu, then the chef spoke back to the student queuing in front of me in Portuguese.

Canteens exist on their own scale of inclusivity. Close to the Campus Condorcet in Aubervilliers is Taf & Mafé, a long-standing charitable canteen that helps newly arrived African migrants with culinary experience to cook professionally. They serve 600 meals daily from a mostly north and west African menu, from couscous and merguez to thiéboudienne, gombo and mafé. The canteen is on the ground floor of a building that provides social housing to vulnerable people, who can eat a generous meal for €3. The non-resident price is €4.50, and people from across the area make the journey: residents, men of religion, campus workers, librarians and a handful of students. The food is excellent – better than at the Crous.

For all the diversity of the restaurants universitaires, the security guards who check my bag at the Campus Condorcet opt to eat at Taf & Mafé instead. The Crous might be a tangible form of solidarity for lots of students, but its arrival in megacampus form exists alongside hundreds of bonds already at work against food insecurity and social exclusion (85% of households in Seine-Saint-Denis live in a district at risk of food insecurity). In Aubervilliers, it’s through the exclusion of local, often marginalised and racialised, communities that students appear to benefit from vast spaces, state-of-the-art kitchens and subsidised rates.

Day Three: La Barge du Crous, River Seine, Quai François Mauriac, 13th arrondissement

Menu du jour: endive, blue cheese and walnut salad, beetroot and mâche – cordon bleu, chips and green bean, white asparagus and aubergine medley – fruit salad

The easternmost part of the 13th arrondissement hugs the River Seine, just across from Bercy coach station. Here, too, aggressive redevelopment has changed the face of the area. It began in the 1980s with the arrival of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, pet project of socialist president François Mitterrand, whose name adorns the library. Further south is the new campus of Paris-Cité University, on a former factory site, Grands Moulins. Here, a faux-English pub, the Frog and British Library, welcomes drinkers.

In 2013, the Crous bought and renovated a three-floor barge. It was inaugurated in 2015 by another socialist president, François Hollande. The deck has outside seating looking on to the river, and Le Rooftop, a bar that is open until late. I have seen all sorts come here to photosynthesise in a genuinely public space in an otherwise corporate postcode. I imagine cooking on a river has its limitations, but the food is decent. Today, it is a bistro classic and presidential favourite: cordon bleu. Alongside, an endive, walnut and blue cheese salad fit for a bouillon lifts an otherwise merely effective meal.

I ask the people sitting next to me a few questions, which are met with a sideways glance. I rapidly explain, without realising how odd I must’ve sounded, that the canteens here were all I ever wished for across the Channel. Maxime and Julie are students at Paris 1’s Tolbiac campus, around 20 minutes away on foot. They reply matter-of-factly that their favourite dish is indeed the cordon bleu. ‘Most of all, we come for the choice. Every canteen has its own variety, especially at Paris-Cité just down the embankment.’ I ask why they come here instead. Maxime responds with a shrug and gestures to the river.

Day Four: Cité Internationale Universitaire de Paris, Boulevard Jourdan, 14th arrondissement

Menu du jour: chickpea, tomato and cheese salad, bread – coley with sauce bordelaise, spaghetti and courgettes – fromage blanc

During the interwar period, 34 hectares of Parisian land were given over to the construction of housing for students from around the world. Intended as a peace project, this now makes up the Cité Internationale Universitaire de Paris. Like many other foreign students arriving in Paris, my first port of call was the Cité, which is like a small town in demeanour and sheer size, with its 12,000 residents.

Today, the Cité boasts 7,000 rooms in 47 ‘houses’, each representing a foreign country. Sixty per cent of residents in each house are nationals of the house’s country (Italians live in the Italian House, and so on), and the remainder is a mix of all other nationalities. If your country hasn’t yet got its own exclave – for reasons as varied as diplomatic spats, corruption or lack of space – with a bit of luck, you will be welcomed by another. (I was placed in the Le Corbusier-designed Swiss house for a year.) Some of the houses have their own commercial restaurants that are open to the public (Korean House has the best reputation, with the Germans not far behind), with slightly cheaper rates for residents, but most students eat lunch and dinner at the central canteen, or cook where possible.

The Crous won the tender to run the Cité’s central canteen in 2018, renovating it to the tune of €1.5m. It’s a remarkable operation, with almost 500 seats. The greater choice that this canteen offers is both a blessing and a curse. To the left is a chef baking pizzas, setting his peel down to serve the vegetarian meal. There is a generous display of charcuterie, a mix of terrine, prosciutto, chorizo or rosette, unfailingly accompanied by a single cornichon. The crown jewel of the set-up is the grill. At every service, there will be grilled meat or fish (with chips, the much-memed Crous staple) cooked as you wait.

Today I go for the fish and courgettes with spaghetti. Having lived here for a year, I know what to expect of the ‘sauce bordelaise’ (which is more of a puttanesca, olives and capers giving the game away) that coats the fish. I keep it simple: tomatoes, chickpeas and cheese as my side, and to finish, some fromage blanc (which, today, is missing its chestnut cream topping). I enjoy my meal, though I can always do without the spaghetti. The sauce is sharp, the coley is fleshy and sustainable (so I am told), and so today, again, I cannot complain. I empty my tray and complete my lap of the cafeteria, after picking up an espresso, for 60¢.

I sit down next to an older man called Mustapha who was just in front of me in the queue for coffee. He tells me that, as an engineering student in the 70s, he lived in the Cité for four years: three in Lebanon House, the country of his birth, and one in Japan House. Mustapha is a discerning diner: he prefers the Mabillon canteen, but comes to the Cité’s since he lives nearby. He eats in the German House when the Cité has its veggie-only days. But he continues to be a regular here because of its cadre agréable – its pleasant setting, with students chatting and bustling past the high windows overlooking the park – and its honest fare. As a non-student, Mustapha pays €8.80, and he is all too happy to: ‘I come here at least once a week, when I’m in a hurry and can’t go to a local restaurant.’ I want to understand if the food itself, more than the convenience, atmosphere and nostalgia that come with it, is really what keeps him coming back to this restaurant universitaire. I ask him what he makes of the cooking: ‘Pas mal.’

Credits

Jack Franco works on projects to increase access to language learning, and researches the social philosophy of contemporary China. Born in Italy and raised in London, he is currently living in Paris.

This supplement was subedited by Tom Hughes and Liz Tray. The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

Loved the diary format and being taken through many of the arrondissements!

wow, that was an outstanding read! I mean, not completely romanticising the cateens and including a subtle critique of the exclusions and exploitations they rely on... But, then again, these kinds of university food provisions are 'normal' in many parts of the world. Would be fun to do a comparative piece eating in London uni canteens (£6-8 lunches, honestly not bad for London, but run thru pvt contracts rather than a union and should definitely be further subsidised for students)