School Lunches: the Last 120 Years

From nourishing soldiers of empire, to the founding of the welfare state and its recent decline – a century in school dinners. Words by Lexi Earl.

Welcome to Vittles Season 7: Food and Policy. Each essay in this season will investigate how a single or set of policies intersects with eating, cooking and life.

For our fourth week, we have contributions by Lexi Earl, Thea Everett, Will Yates, Katie Randall and Laura Thomas on how policy has, and continues to affect eating and food education in British schools. You can find the whole series here:School Lunches: the Last 120 Years

A Chat With a Dinner Lady

Why is Food Education so Unappetising

The Tuck Shop Diary

In this essay, Lexi Earl tells the story of school lunches over the last 120 years, from Victorians nourishing soldiers of empire, to the founding of the welfare state – and its subsequent decline with the rise of neoliberalism.

School Lunches: the Last 120 Years

From nourishing soldiers of empire, to the founding of the welfare state and its recent decline – a century in school dinners. Words by Lexi Earl.

In 2020, deep in the Covid pandemic, footballer Marcus Rashford called for the English government to extend free school meal provisions by serving meals for hungry children during the summer holidays. But why might the state be involved in providing nutrition for children? The answer lies in the very origins of school meals in the UK, which suggest their purpose extended beyond mere fuel. From the nineteenth century onwards, food became a way for the state to shape children into particular kinds of citizens, with the school dining table as a source of ‘civilisation’, say. Since the beginning, school meals have provided an avenue for the state to get involved in the making of the child’s body.

1870–1900: nourishing future soldiers

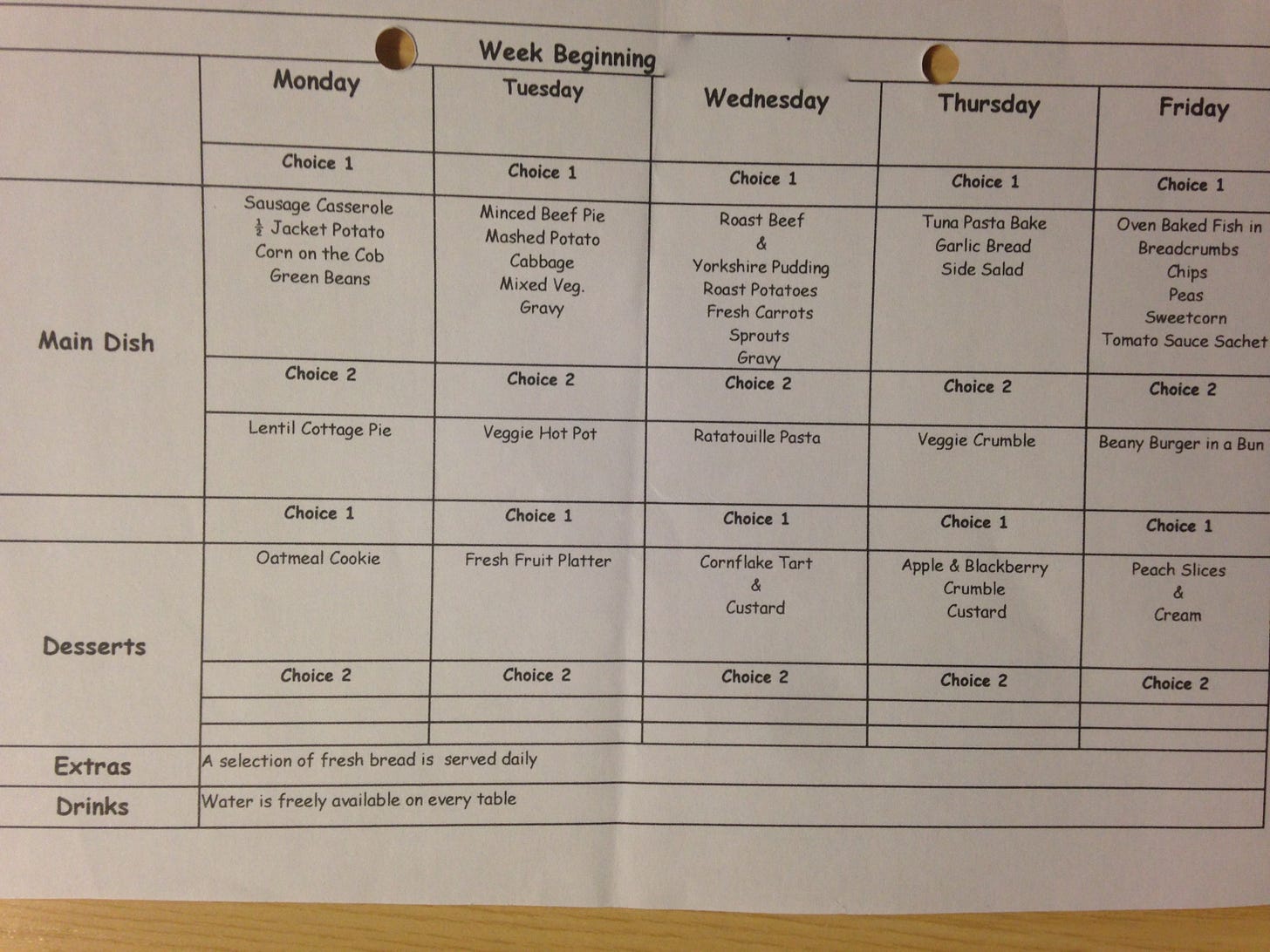

Sample menu: porridge, broth, fruit

One of the reasons for the early focus of state involvement in children’s diets was to ensure a steady stream of well-nourished and strong soldier recruits for Britain’s military expansion and colonial conflicts (the Boer wars, the Second Anglo-Afghan war and the Third Anglo-Burmese war, among others). Hungry and malnourished children were more easily identified after the Liberal government’s Education Act of 1880, which made schooling compulsory for all children between the ages of five and ten. Having hungry children in classrooms who were unable to learn undermined the efforts of the universal education to mould children as citizens of the British empire. Charities stepped in to fill the gap too, and in Manchester, Bradford and London, some school boards starting serving meals in the 1880s. Meals largely featured oat porridge, broths and fruit, and were targeted at the neediest children.

1900–1930s: bread and dripping

Sample menu: meat stew, bone broth, treacle tart

In the 1900s, school meals became a more formal part of school life, with the Education (Provision of Meals) Act (1906) introduced by the Liberal government under Henry Campbell Bannerman. This authorised Local Education Authorities (LEAs) to provide meals for children, but did not make them do so (an attempt to appease those members of government who worried the state was becoming too paternalistic). Tablecloths, flowers, and older monitors to serve food made the school meal an educational event situated within the school day and provided those children of the so-called ‘deserving poor’ with an example of what might happen in a family home. Foods served were typically Victorian in outlook (think simple and bland) and included porridge (with milk or treacle), bread with dripping or margarine, and soup made from bones.

By 1909, 113 school canteens were serving around 116, 000 children a year (4% of children in schools). Those who did not eat at school generally went home for a lunch provided by their mothers or a neighbour. The Great Depression of 1929–1932 saw a sharp increase in meal uptake to over 600,000 meals per day (approximately 12% of children in schools, largely for free). The meals served in the late 1920s included warm cocoa or soup, both with bread, and by the early 1930s began to resemble those for which the meals service is famous: stews, hot pots, and treacle tart. Free milk was provided nationwide from 1934 onwards, an initiative of the Milk Marketing Board, made official by the Milk Act (1934).

1940s–1950s: A war effort and the welfare state

Sample menu: corned beef, meat and two veg, chocolate semolina pudding

In 1940, in an bid to get more women into the war effort, the government decided LEAs should provide meals to all families that desired them. Attempts to implement this were hampered by bombing and a lack of equipment, but increased funding in 1941 stimulated local authorities into intensifying efforts to provide meals. Children either received meals for free or paid the cost of the meal. Another government circular at this time established some nutrition standards: a lunchtime school meal should provide 1000 calories, 20–25g first-class protein and 30g fat.

In 1944, a coalition government under Winston Churchill introduced the National School Meals Policy, and LEAs had to provide meals for all children. The era of ‘meat and two veg’ (and pudding) – a symbol of the more paternalistic welfare state – was ushered into being. The government also published proper nutrition guidelines, although these were never implemented. As food was still being rationed, school cooks had to make use of canned fish and meats, potatoes, and tinned desserts when designing their menus. Rationing continued until 1954, after which dishes like fish and chips, corned beef, blancmange, and chocolate semolina pudding started to appear on the menus were distributed by local councils – such as those in the School Meals Service Recipe Book distributed in Surrey in 1956.

Today, the school meals in this era are now looked back upon with nostalgia. The time is considered aspirational (by some) because of its simplicity – in home life and work life, and, for children, its provision of nutritionally beneficial meals. These meals continue to exist to this day through Roast Dinner Wednesdays, a weekly occurrence in most primary schools which provides the equivalent of a British Sunday roast dinner (with veggie options too), including stuffing and roast potatoes.

1970s–1990s: Individualism and ‘freedom of choice’

Sample menu: tomato and cheese pizza, chips, sprinkle cake and custard

The service of school meals might have continued this way, had it not been for the economic upheavals of the 1970s and the rolling back of the welfare state. The Conservative government (1979–1997) sought to cut expenditure across a range of public services, one of which was school meals. Free milk was abolished in the early 1970s, when ‘Thatcher, Thatcher, milk snatcher’ became a regular taunt from the press (Margaret Thatcher was Secretary of State for Education and Science from 1970–1974). Although the meals service was providing 5.5 million meals a day in 1970, over the next ten years take up decreased dramatically from 70% in 1973 to around 40% in the mid 1980s. The decline in take up of school meals mirrors the increase in their price due to inflation and then government removal of national pricing limits for school meals in 1980. Many families switched to packed lunches to save money. Rather than being the responsibility of the government, children’s lunchtime nutrition was now deemed the responsibility of their family, with children being regarded as consumer-citizens, capable of freedom of choice. State interest in moulding children’s diets waned.

The Education Act (1980) no longer required local authorities to provide meals to children except those receiving them for free. Nutrition standards were abolished. The Local Government Act (1988) introduced Compulsory Competitive Tendering. This obliged LEAs to put their meals services out to tender and required them to accept the lowest price. This ushered in the era of pizza, chips, turkey twizzlers and hamburgers. Vegetables largely disappeared, and any notion that a school meal might be part of a child’s wider educational experience was eliminated. Highly skilled school cooks became box-openers and food-reheaters.

2001–2013: The early noughties

Sample menu: pasta bake, chicken curry, apple crumble

The advent of the modern school dinner is sometimes traced back to the airing of Jamie’s School Dinners in 2005, although provision had already been made by the New Labour government for the reintroduction of food-based standards in 2001. Concerns about children’s health – and more specifically, their fatness – had been growing throughout the 1990s. A Food in Schools programme was launched to help develop whole-school approaches to eating and drinking. But of course, like all bureaucratic entities, the meals service was, in practice slow to change. Skilled cooks had been replaced by unskilled staff; kitchens had been abolished or were without necessary equipment. With the exception of a handful of schools (particularly primaries, who were quick to change their approach), this continued to be a challenge for most schools, due to budget constraints and the expectation of multiple choices of lunchtime meals.

In May 2012, a young girl in Scotland started a food blog called Never Seconds. In it, she documented the lunches at her local primary school. Her pictures provide a snapshot of primary school meals in the early 2010s and feature macaroni and cheese; sausages and potatoes; chicken fajitas; soups plus sides of vegetables; and fruits, yoghurts or cupcakes. By this time, the meals service had moved beyond offering only traditional British foods and started to include more variety – curries, tacos, pizza, pastas – alongside roast dinners, fish on Fridays, or sausages and mash. However, while often implemented in the spirit of celebrating diversity and embracing immigrant communities, these meals tended to be the ‘British version’ of a particular dish, and therefore not recognisable to the children that menu planners and cooks were trying to include.

In 2013, the School Food Plan was published by the Department for Education, and with it a new era of school food began. While the School Food Plan was only a review, with no actual funding for change, it changed thinking about lunchtime, transforming it from mere fuel into an integrated part of the school day. The kinds of lunches advocated by the School Food Plan were those cooked in-house by skilled cooks, featuring a balanced plate with vegetables and fruit as well as proteins and carbohydrates. Processed, fried, and convenience ‘beige’ foods were out. As set out in Earl, Schools and food education in the 21st century cooking from scratch, gardening, and so-called ‘foodieness’ were in (although, in practical terms, very little changed except in schools where teachers, head teachers or cooks spearhead initiatives).

2020s: footballers and free school meals

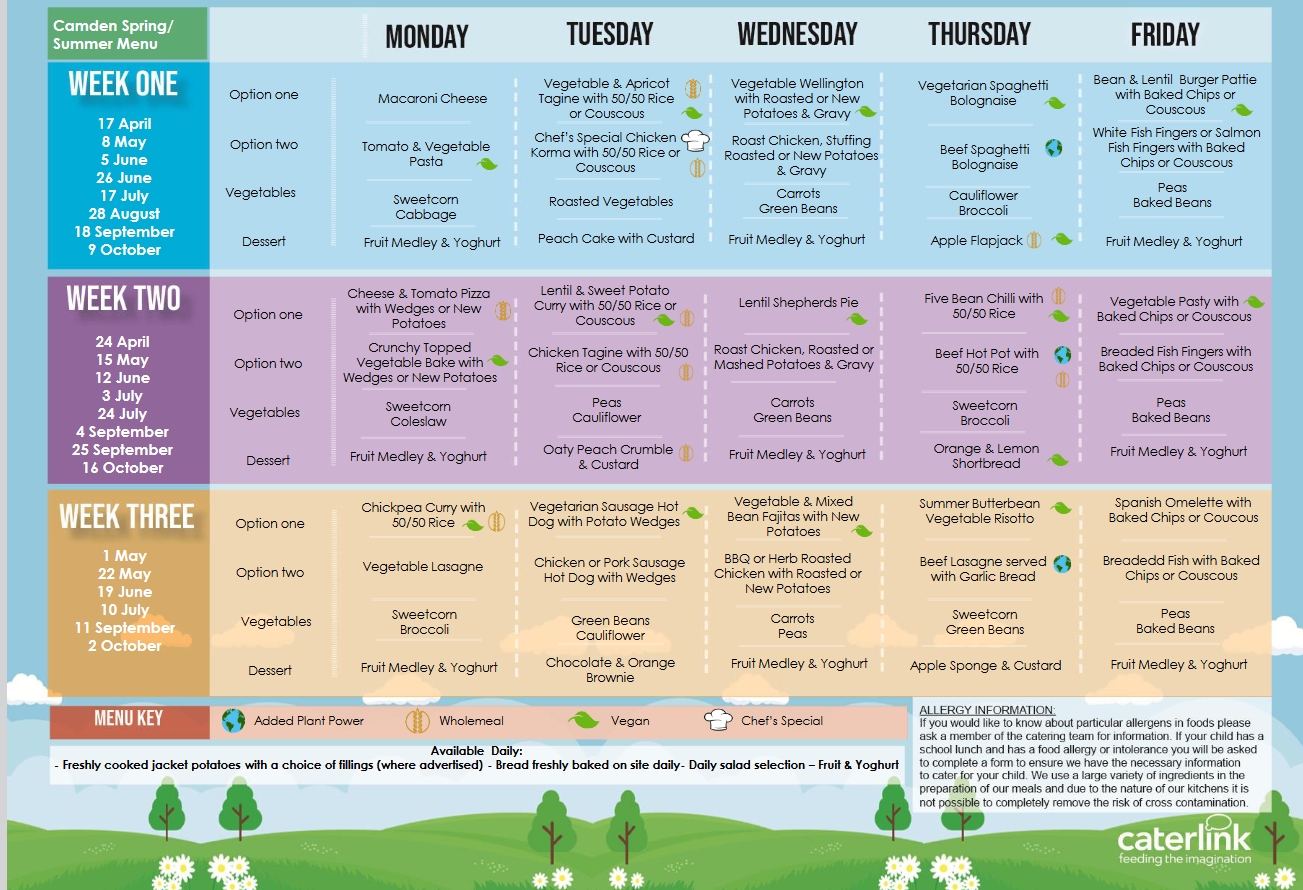

Sample menu: chicken tagine, lentil and sweet potato curry, fruit and yoghurt

As we approach nearly 120 years of the school meals service, what has changed? Shockingly, the number of children coming to school hungry is still remarkably high – 23.8% of children in England were eligible for free school meals in 2023, up from 22.5% in 2022 and 17.3% in 2020. Diseases of malnutrition, including scurvy and rickets, have reappeared. If this makes you rage, so it should. That a wealthy country like the UK has so many children living in poverty, in states of malnourishment, is a scandal.

Corporate control of the school meals service remains an issue. Meal parcels delivered by these companies during Covid lockdowns caused a stir on social media when parents posted images of what they had been provided: white bread, baked beans, sliced cheese, yoghurts, some fruit, some potatoes, some pasta. The cost paid to the provider was reported to be between £10.50 and £30, while the food provided could have been bought for around £5.

One issue is that the framing of how to change school dinners is still based around children’s body weight; any policies – and plenty of charities, NGOs, and others – frame children’s body weight as a problem. The logic is thus: eat more healthily – less beige foods and more fruits, vegetables, wholegrains, lean proteins – and you will be thin. Better still, teach children how to eat healthily (through cooking and gardening), and they will eat better, teach their parents to eat better, and none will be a burden on the health service (because they will be thin). This rhetoric hides the very real structural reasons children might be fatter (food and fuel cost, access to varied foods, time to cook, lack of outdoor space etc), and moves the responsibility of health to the individual family – often exclusively to mothers – and the child. It is also often couched in perceptions of social class and (mis)understandings of poverty, disguising the severe underfunding that has plagued the health service for over ten years, the damage that a fat-phobic society does to those in bigger bodies, and narrows our understanding of health as equating to thinness.

But there are signs of hope. Charities like Chefs in Schools are bringing skilled chefs into school kitchens. Universal Infant Free School Meals, a compromise of the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government in 2014, provides free meals to all children in Reception and Years 1 and 2, and according to a 2022 study by Angus Holford and Birgitta Rabe, is showing evidence of helping address malnourishment in children across income brackets. Provision for school meals is part of the English Food Strategy, connecting meals to food education more generally, and harking back to the original idea that meals be part of a wider food education curriculum in schools. From September 2023, all primary school children in London are eligible for free school meals. However, commitments to universal provision remain contentious – although the Labour Party committed to universal free school meals in primary schools in their 2019 manifesto, they have refrained from such a commitment in 2023. Universal free school meals would make a difference to all children, particularly those who don’t meet the current threshold for free school meals but still reside in poverty. All children deserve to be well nourished so that they may take advantage of their education, and live their lives with dignity.

A note: school meals were devolved across the four UK nations in 1998 and 1999. This essay refers to those in England.. Education was devolved in Scotland in 1998, in Wales in 1999, and in Northern Ireland in 1999 (with brief periods of direct rule until 2007).

Credits

Lexi Earl is a writer and science communicator, currently managing the Oxford Martin Programme on the Future of Food. She is the author of Schools and Food Education in the 21st Century (Routledge, 2018) and, with Pat Thomson, Why Garden in Schools? (Routledge, 2021). Lexi is interested in the way we feed children, the different actors involved, and how our feeding practices are shaped by policies, the media, social media, families, tradition and knowledge. She writes a newsletter on Substack: nature//nuture.

Sinjin Li is the moniker of Sing Yun Lee, an illustrator and graphic designer based in Essex. Sing uses the character of Sinjin Li to explore ideas found in science fiction, fantasy and folklore. They like to incorporate elements of this thinking in their commissioned work, creating illustrations and designs for subject matter including cultural heritage and belief, food and poetry among many other themes. Previous clients include Vittles, Hachette UK, Welbeck Publishing, Good Beer Hunting and the London Science Fiction Research Community. They can be found at www.sinjinli.com and on Instagram at @sinjin_li

Vittles is edited by Sharanya Deepak, Rebecca May Johnson and Jonathan Nunn, and proofed and subedited by Sophie Whitehead.

Thank you so much for this post and for making this freely available! We covered the history of school meals briefly at university, but I learnt a ton of new information from this amazing piece. Thank you for all the links provided, especially the ones to the charities that are currently tackling this problem (which I had no idea existed)! Thank you for linking the studies too. :)

Hi Lexi - interesting article - but it does need some serious revision: this quote “ While the School Food Plan was only a review, with no actual funding for change” is totally wrong. It was agreed policy with a lot of funding! Do get in touch with me at myles@bremnerco.com - happy to help!