The Real ‘Life in the UK’ Test

Vitória Croda examines Britain's obsession with the meal deal.

Good morning, and welcome to Vittles! Today’s essay, our last of the year, by Vittles mentee Vitória Croda, is a tongue-in-cheek look at one of the hardest parts of integration for any immigrant to the UK: the country’s reliance on the meal-deal lunch. It is the third online-only dispatch from the Bad Food Extended Universe.

Our second print issue – the ‘Bad Food’ issue – is available on our website, along with prints from our favourite illustrators and photographers. Please note that any orders this week are unlikely to arrive before Christmas, but if you’re looking for a last minute present, we do have one option left…

Otherwise, we hope you have a wonderful Christmas and New Year break — see you in 2026!

The Real ‘Life in the UK’ Test

How do you measure integration into a new country? If you ask the ‘Life in the UK’ test – which is also a great icebreaker in immigrant circles – full integration means memorising the names of all of Henry VIII’s wives, or being able to confirm that autocracy isn’t a fundamental principle of British life. As someone who moved here from Brazil five years ago and has passed the test, I feel almost fully integrated. I have got used to the gloomy weather, I have learned to love the noisy London Underground, and I now walk so fast that I have taken up running as a hobby. However, there is one metric I have yet to meet, one which the ‘Life in the UK’ test misses: the ability to happily eat a chilled sandwich.

It didn’t take me long to get acquainted with the ‘meal deal’ – the lunchtime food combo of main (usually a cold sandwich) + snack + drink offered by major supermarkets. In my first corporate job in central London, the meal deal was the closest I got to culture shock. Unlike Brazil, where workers are given a stipend for restaurants and groceries, here employees have to pay for their own lunch; a meal deal is often the only thing that will work with budgets and a half-hour break. Every time I ate a tepid chicken salad sandwich at my desk, I felt like I was eating only to keep my body alive, rather than for pleasure. Maybe that’s why my mother refuses to call these pre-packed lunches ‘real food’. ‘Call it what you want, but this isn’t a proper lunch,’ she argues when I send her a picture, before asking me to eat a warm meal of rice and beans.

With my outsider perspective, I soon realised that what truly unites people in the UK is accepting these meal deals as food. I’ve also noticed that Brits have a very personal relationship with their meal deal combination, which means you can use the most popular choices to judge the current psyche of the nation. In the last few years, I’ve seen more stickers announcing ‘High in Protein’, ‘Source of Fibre’ or ‘Low Fat’, along with complete meal drinks such as Huel and yfood, making the meal deal even more joyless. This year’s ‘Clubcard Unpacked’ showed that the UK’s favourite combo has shifted from the sausage, bacon and egg triple sandwich and McCoy’s steak-flavoured crisps to a chicken club sandwich and a high-protein pot of hard-boiled eggs.

As I see people around me unbothered about their daily meal deal, I start to wonder if I will ever feel like a ‘fully integrated’ immigrant. My partner, on the other hand, has completely accepted the meal-deal mindset. ‘I’d rather eat something cheaper now and spend more on a date with you later in the week,’ he tells me dubiously, although I feel flattered by his selfless sacrifice.

So, he has passed the real ‘Life in the UK’ test, but not me. Not yet. To try and pass it, I decided to eat meal deals for five days in a row to see if I’m able to fully belong in this place I now call home.

Day 1: Tesco, St Paul’s

I decided that each day I would choose a different supermarket – or pharmacy, if you include Boots – at which to buy my meal deal. For my inaugural lunch, I entered the first Tesco I saw around St Paul’s station (I’ve noticed Tesco tends to dominate conversations about supermarkets’ meal-deal lunches). It was half past noon, which meant I needed to be quick – gilet-wearing dudes were already packing the aisle, breathing heavily to hint that I was in their way. I was rushed into choosing the tuna sweetcorn sandwich. It wasn’t bad, but at the same time, it wasn’t exactly good – which is a summation of the meal deal. I got my sandwich with a side of sliced carrot and hummus dip for my fibre intake, plus a small carton of coconut water, which I must admit was surprisingly tasty (don’t tell my coconut water-purist Brazilian friends). In less than thirty minutes, I was all fed for exactly £3.85, but the real cost of this convenience is flavour.

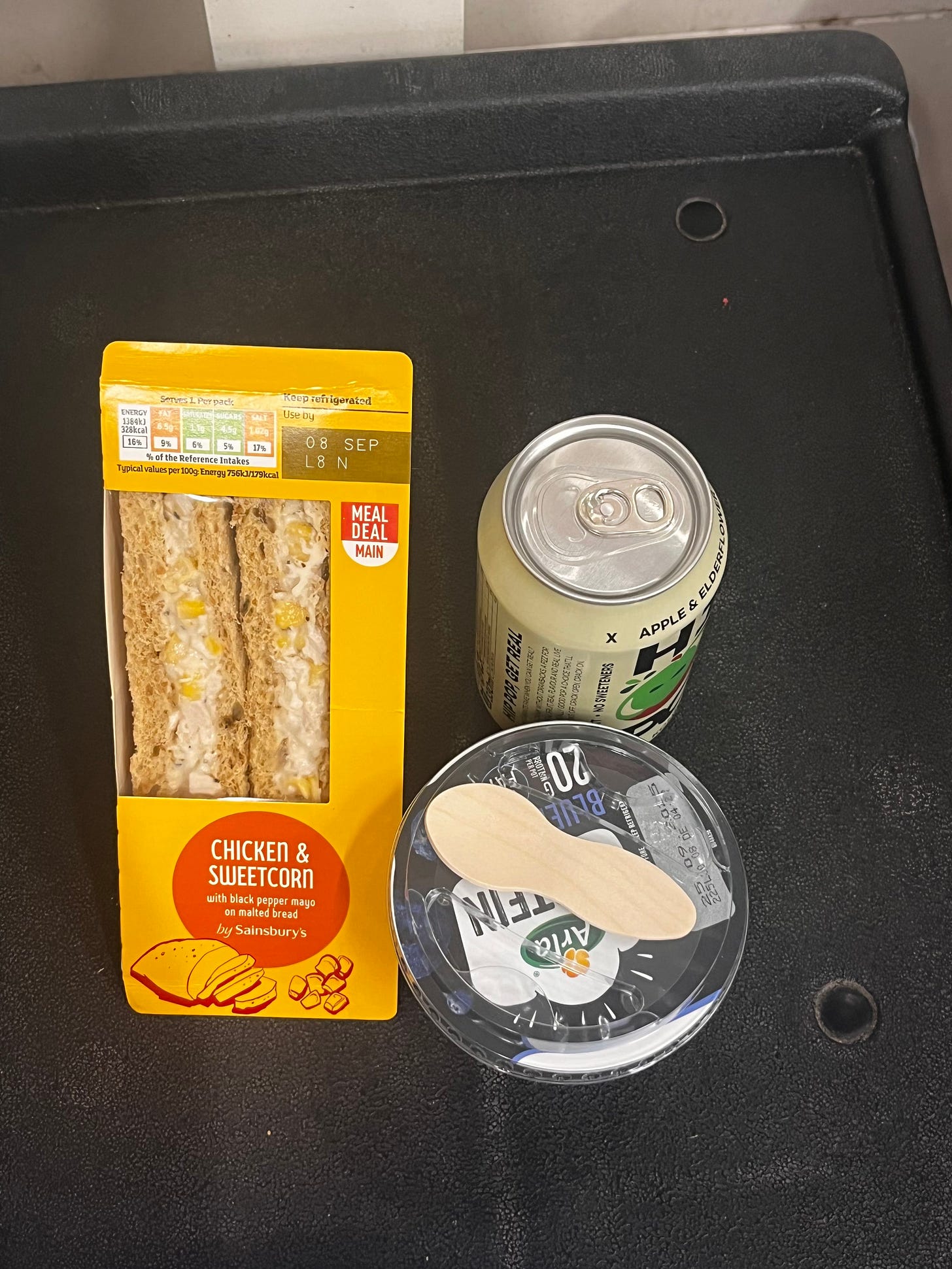

Day 2: Sainsbury’s, London Bridge

The meal-deal aisle at the London Bridge Sainsbury’s was almost identical to that of Tesco’s, but here the meal deal cost £3.95. I got the only thing I couldn’t recall seeing the day before: a chicken and sweetcorn sandwich, which unnervingly didn’t taste much different to the tuna one. I decided to get a high-protein blueberry yoghurt as a snack – it seemed like everyone around me was getting this as well. Although popular, the yoghurt tasted so artificial that I doubt it contained a single blueberry; I felt sorry for the cow that was milked to make it.

Maybe my standards were too low at that point, but my canned apple and elderflower kombucha was a pleasantly tart, refreshing surprise. This was probably my most ‘fit’ lunch of the diary. In numbers, it had fewer than 500 calories, over forty grams of protein and no more than seven grams of fat. I felt like this entire lunch was built by the algorithm – probably the same one that made me sign up to run a half-marathon on the hottest weekend of September.

Because I was raised Catholic and unconsciously seek penitence, I ended up sentencing myself to eat my Sainsbury’s meal deal right next to Borough Market, where tourists were having their fill of truffled sandwiches, empanadas and oysters. Even the strawberries with chocolate topping seemed worth £8 in that moment. But I needed to pass the test, so I kept chewing the cold and slightly stale bread. As soon as I finished my combo, I headed into the market and got a mango sticky rice from Khanom Krok.

Day 3: Marks & Spencer, Brixton

From my observations, the supermarket you shop at says a lot about your social class in the UK. People back home don’t fully seem to grasp this, even though inequality is rife in Brazil. Although different supermarkets in Brazil have their own target audience, for Brits, your preferred supermarket becomes as much a part of your identity as being from Manchester or supporting West Ham. To understand what kind of chilled pre-packed sandwich was being offered to the more affluent classes in the UK, I decided to go to the Marks & Spencer near my home in Brixton.

Unlike everywhere else, M&S doesn’t offer a typical meal-deal combo. The sandwich alone costs £4.60, which is more expensive than most of the meal deals I tried throughout the week. To be fair, it was the only supermarket lunch with a significant difference in taste. The beef and horseradish mayonnaise sandwich had fresher bread, and the spicy horseradish stood out against the dull mayo from Sainsbury’s and Tesco’s. I still ended up feeling hungry a few hours later; luckily, I had some leftovers from the previous night’s dinner. Although I hate to agree with my mother, as I was eating, I realised she was right: the meal deal isn’t a complete lunch.

Day 4: Boots

The most interesting thing about immigrating is how much you learn about your home country. For example, learning that there is a pharmacy chain in the UK that sells lunch alongside sex toys has shown me how prudish we can be in Brazil, despite stereotypes. Back home, vibrators are usually tucked away in specialised adult shops only, not sold alongside chilled pasta salads and protein bars.

Boots is indeed quite convenient, but buying a bullet vibrator at Boots Cheapside feels more dignified than getting its meal-deal lunch. Imagine telling your friends back home that you just spent £4.50 – or £4.99 if you don’t have an Advantage Card – on a combo of a dry and crumbly chilled ham and egg club sandwich, an insipid chocolate mousse, and the one carton of coconut water you drink to gaslight yourself into believing it’s not all that bad. At the end of the day, I bet the sex toys were gone but the sandwiches were still there.

Day 5: Pret a Manger

I started to realise that I might never actually enjoy – or even tolerate – a cold sandwich for lunch. Suddenly, the voices of Nigel Farage’s supporters echoed in my head: ‘Go back to your country.’ So I packed my bags and went straight to Gatwick, where I ate at Pret a Manger.

Pret is a phenomenon I’ve never understood. It’s expensive and doesn’t particularly taste better than any chain supermarket. Yet there are always British people lining up at every central London branch, waiting for their watery coffee and average food. I thought I could escape this, but there’s no way to complete the ‘Life in the UK’ test without having a Pret lunch. This one was particularly pricey – £11 for a dry ham and cheese sandwich that almost crumbled into powder, a mango and lime snack pot and a bottle of still water. We all know airport food exists in its own logic, but this felt exploitative.

As I was leaving the country, I looked over to the plane window with a sense of sorrow, feeling like I had failed my personal exam. I still couldn’t feel a modicum of pleasure or happiness when eating a meal deal. But, soaring high in the sky, I listened to Pink Floyd, and as Richard Wright sang, ‘Hanging on in quiet desperation is the English way’, I finally understood what it meant. Maybe this was enough.

The time is gone, and twelve hours later I’m at my mother’s home in Brazil. She feels sorry for me and cooks me lunch. Rice, beans, sun-dried meat, okra and pumpkin salad. On a plate, not in cardboard. ‘Finally, a real lunch,’ and I sighed in relief.

Vitória Croda is a journalist and immigrant from Brazil. She’s been in London for five years, and is currently doing her PhD at Loughborough University.

The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

Related Reading

Aaron Timms on the Erin Patterson trial

Mariam Abdel-Razek on the decidedly unromantic reality of cooking in a professional kitchen

Thom Eagle on how the customer is not always right

I’m mixed heritage but born and brought up in London and I had so many feelings reading this, swinging from wildly defensive to also conceding with a nod that a cold Sainsbury’s chicken sandwich is a pretty sorry affair. I guess everyone knows the meal deal is a little bit shit and that’s part of its charm? Without the culture of stopping for lunch (many eat on the go or work through their lunch break), it’s just the means to an end - I can see how this would be problematic for many!

Italian living in Scotland here - having just passed my Life in the UK test I feel this so much! I think one of my first culture shocks when I started working full-time here was indeed the quality of food people have for lunch and the lack of time to eat a proper meal. I try whenever I can to have some home made food to carry with me. Cheaper and more fulfilling than these cold sandwiches. I honestly can't cope, would take a soup deal any day!