The Rise of MiddleEastMediLevantia

What is the British Jewish restaurant now? Words by Josh Dell

This article is a part of Vittles British Jewish Food Week. To read the rest of the essays and guides in the project, please subscribe below:

The Rise of MiddleEastMediLevantia, by Josh Dell

What is the British Jewish restaurant now?

Londoners can’t get enough of Jewish food – they just don’t know it. Over the last decade, a wave of restaurants serving Sephardic and Mizrahi Jewish food have utterly changed the London restaurant scene, specialising in an eclectic style of cuisine while mainstreaming ingredients and techniques into the canon of modern British cooking. The dominance of these restaurants in central London is arguably the most successful representation of Jewish food in British history. NOPI, Honey & Co., The Palomar, ROVI, The Barbary, Coal Office, Oren, Delamina and Miznon – between them they have picked up dozens of broadsheet reviews, occupied some of the busiest real estate in the city, been the catalyst for national recipe columns and books, and – through their success – have changed not only the way London eats, but the whole country, too.

This cohort of Jewish restaurateurs and chefs serve a cuisine that is unrelated to that served by the generation before them. The major Jewish culinary contribution of the twentieth century was Ashkenazi cuisine – easily identifiable as European and openly identified as Jewish. The major Jewish culinary contribution of the twenty-first century is a set of restaurants, newspaper columns and cookbooks whose strength is a lack of identity (beyond basic Middle Eastern geographic markers). Where the Nosh Bar and Bloom’s traded on their Jewish identity, many of these new restaurants use other descriptors: Levantine, Middle Eastern, Mediterranean, as if they come from an ambiguous land called MiddleEastMediLevantia. Even more notably, they nearly all avoid mentioning the place that serves as the home of their founders or the inspiration for their food: Israel.

The Palomar – ‘Our menu is influenced by the rich cultures of Southern Spain, North Africa and the Levant’

Coal Office – ‘An immersive dining experience mirroring the unique, engaging traditions found throughout the Middle East & Mediterranean’

Honey & Co. – ‘Serving up delicious Middle Eastern food’

Miznon – ‘Bringing the flavours of the Mediterranean to London’s most vibrant neighbourhoods’

Oren – ‘Mediterranean-inspired small plates’

The Black Cow – ‘A Middle Eastern steak house’

The Barbary – ‘The restaurant takes inspiration from the Barbary Coast, identified by 16th century Europeans as the area settled by the Berbers in the Atlas Mountains.’

Shuk – ‘A market stall inspired by childhood memories of family, pita, spices & tahini’

The Good Egg – ‘Our independent all-day restaurants serve up dishes inspired by the flavours of the Middle East’

Anita Gelato – ‘Anita’s world-famous boutique ice cream had modest beginnings in a small Mediterranean kitchen’

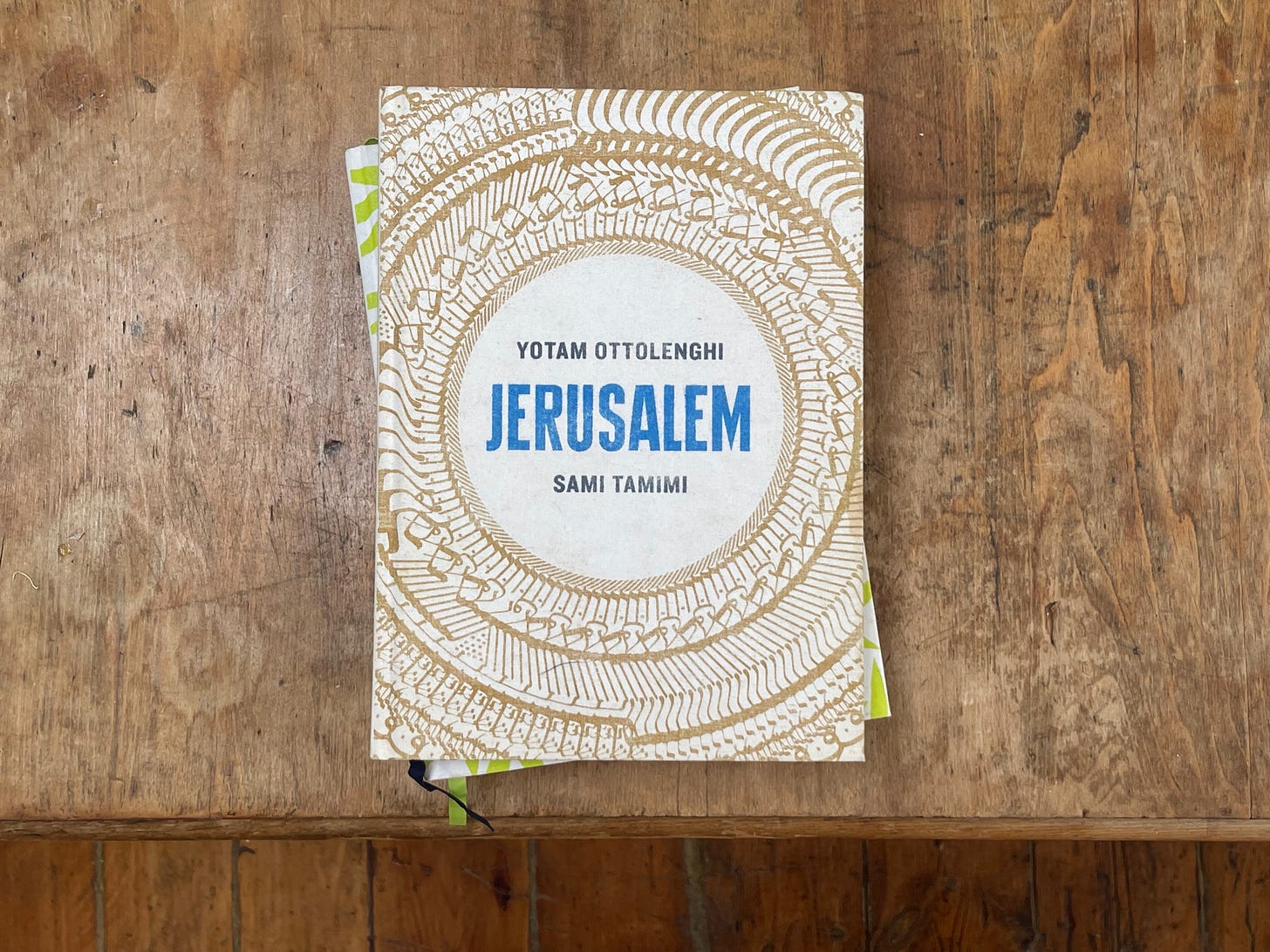

The emergence of MiddleEastMediLevantianism in the UK can be traced back to 2012, with the publication of Yotam Ottolenghi and Sami Tamimi’s cookbook Jerusalem. Prior to this, Ottolenghi had been famous for his delis and recipes, which traded in an amorphous cuisine more rooted in certain ingredients and flavour profiles than the food of one country or region. Jerusalem marked the first time that Israel became central to Ottolenghi’s public identity. In the book’s introduction (which Ottolenghi has explained he would write differently now) the authors establish a shared and equal ownership over the region’s cuisine, writing that ‘arguments about ownership, about provenance, about who and what came first… are futile because it doesn’t really matter’. That same year, Sarit Packer (who was executive chef at Ottolenghi’s NOPI) and her husband Itamar Srulovich (who was head chef at two of Ottolenghi’s delis) opened Honey & Co. on Warren Street, serving food inspired by their childhoods in Israel. The sign over the front door read ‘Food from the Middle East’; this led to confusion. Srulovich recalls the frequency with which a customer would turn to him at the end of a meal and say, ‘What are you, some kind of [insert Lebanese/Turkish/Greek] restaurant?’

Within a few years, new generations of London’s Jewish restaurants operated by Israelis, or inspired by Israel, had blossomed – none of them explicitly Jewish or Israeli, but each with their own take on MiddleEastMediLevantianism: The Palomar, which opened in 2014; The Good Egg (2015); Berber & Q (2015); The Barbary (2016); and Coal Office (2018). By 2019, these restaurants had received so much critical acclaim that Claudia Roden could accurately describe the phenomenon as the ‘mainstream[ing]’ of Israeli food within the UK. At the same time, a similar wave of restaurants opened in the US, like Brooklyn’s Miriam (which boasts of a ‘uniquely, distinctly Israeli’ cuisine) and Laser Wolf (‘award-winning Israeli cuisine’).

One of the reasons none of the London restaurants refer to themselves as serving ‘Israeli cuisine’ is that it is debated – between both food scholars and Israeli chefs themselves – whether ‘Israeli cuisine’ even exists. Academics Dr Ronald Ranta and Dr Yonatan Mendel argue that it’s not appropriate to refer to this style of cooking as a cuisine; rather, it should be termed ‘Israeli food culture’. They make the case that this food culture has emerged in under eighty years, and draws on dozens of influences from Jewish communities across the world that have been thrown into what Srulovich described to me as a ‘melting pot of amazing culinary traditions’ in an extremely short period of time. In a landmass the size of Wales, Jews from states spanning America to Yugoslavia were united solely by religion. Ronit Vered, a journalist and food researcher at Haaretz, argues that Israel’s food culture is ‘young in a way and you can’t define it. Think about Italian or French chefs – you have a method established 200–300 years ago.’

For Ranta and Mendel, ‘food culture’ is part of Israel’s wider nation-building project, focused on creating an ‘imagined community’. Unlike other (organically developed) nation states, Israel had to unite Jews from all over the world and turn them into Hebrew-speaking Israelis within a short period of time. This was done, in part, by creating an explicitly Israeli food culture that did not acknowledge the origins of the foods it contained, especially those native to the Levant. (When Claudia Roden released her Book of Middle Eastern Food in Israel, the term ‘Middle Eastern’ was deemed so unsellable that the book’s title was changed to Book of Mediterranean Food.) In Decolonising Israeli Food, Ranta and Daniel Monterescu describe a phenomenon that they term ‘cosmopolitan appropriation’, whereby restaurants helmed by Israelis focus on how they are creating not Israeli food but ‘a cosmopolitan and inclusive food culture that embraces various influences…infused with their own cultural heritage and passion.’

Most of the Israeli chefs I spoke to confirmed to me that using ‘Israeli’ as a term to describe their cuisine felt inaccurate and limiting because of the range of influences they draw upon. This broad identity is something that Srulovich acknowledges at Honey & Co.’s latest restaurant, where the words ‘Food from the Middle East’ no longer appear over the front door. Srulovich said he and Packer found they were ‘taking more and more influence from elsewhere, and the phrase no longer clearly represents who we are’. He added, ‘We also felt the world has moved on in the ten years since we came up with the tagline, and the use of East; Middle East; West doesn’t sit so well for us.’ For Srulovich the answer is not to pivot towards branding the food as Israeli, but something even broader: he points out that a recent dish on their menu uses soy sauce, a condiment with no basis in the Middle East.

One exception to MiddleEastMediLevantianism is Eran Tibi’s restaurants, Bala Baya and Kapara. Reflecting on his time at the Ottolenghi restaurant group, Tibi recalls being briefed by Ottolenghi’s Palestinian co-owner Sami Tamimi that staff shouldn’t comment on the geographical origins of what was being served because ‘food has no boundaries’. Bala Baya and Kapara, on the other hand, are explicit about their Israeliness (Bala Baya’s mission statement is to bring an ‘authentic taste of Israel to South London’). Tibi believes that he is doing what other Israeli-owned and inspired restaurants in London don’t do, telling me that ‘[We] all say we are bringing a new wave, but we’re not saying where that wave is coming from.’

Antisemitism, and fear of antisemitism, unquestionably plays a role in why some Israeli chefs choose not to describe their food as such. Tibi claims his restaurants’ phone lines are monitored by anti-terrorist police due to the regular calls they receive from people purporting to represent terrorist organisations – ‘Hamas, Al-Qaeda, you name it – all of them are calling me’. Other chefs describe that, when tension flared up in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, abusive calls would be made to their restaurants, making terms like Middle Eastern or Mediterranean – or urban descriptors like ‘Jersualem-style’ or ‘Tel-Aviv-influenced’ – more comfortable and neutral. In a September 2023 piece for the Spectator, Jewish Chronicle editor Jake Wallis Simons argued that the absence of the term ‘Israeli’ across much of London’s restaurants was a reflection of how ‘Israeli culture has been attacked as a way to undermine Jewish legitimacy in the Middle East’. Noting that Chinese restaurants still refer to themselves as Chinese, despite the actions of the Chinese government, Simons implies that Israeli-helmed restaurants have been ‘forced’ to rebrand themselves due to the form of antisemitism he argues has emerged through ‘anti-Israel sentiment’.

The imprecision with which the MiddleEastMediLevantian restaurants describe themselves has a mirror image in the way Turkish and Lebanese restaurants used to define themselves as Mediterranean in the 1990s and 2000s, fearing that using the names of their home countries had would have less recognition for an audience used to Italian and Greek food. Fadi Kattan, the executive chef at Akub – London’s first Palestinian restaurant to be pitched at the same mid-to-high-end market as Honey & Co. and Ottolenghi’s Nopi – tells me of his frustration with the use of these terms by both Israeli and non-Israeli chefs. To Kattan they neuter establishments of their identity, and worse: ‘Imagine this scene in London: you walk around and every restaurant that’s Italian, French, German, Spanish, doesn’t say this anymore and, [instead], say[s], “European cuisine”. How boring would it be? It would be a disaster.’

For Palestinian chefs - like Palestine on a Plate author Joudie Kalla - the realities of life in Palestine mean that she cannot accept a culinary landscape where the specificity of Palestinian cuisine is subsumed by a concept of “Middle Eastern cuisine” - which has the potential to become the definitive synonym for Israeli cuisine. ‘You see other people literally copying your work and using Palestinian historical recipes’ Kalla tells me, ‘and they're naming it “Tel Aviv street food” or “Middle Eastern food” or “Levantine food”, ‘all of which is misleading and an erasure towards Palestinians and the roots of where the food originated from’.

According to the food scholar Krishnendu Ray, obfuscation like this is only possible when one side of a divide wields more power than the other. Noting the difficulty Palestinian chefs face when trying to break through into the fine dining scenes of London and New York, he argues that ‘The risks are always heavier on the people in the bottom of the hierarchy, rather than at the top… the people at the top of it can totally set things aside and say, “I’m just talking about food”’. This is reflected in awards and media coverage: the 2023 Michelin Guide to London lists six restaurants in its Middle Eastern category, which theoretically spans the cuisines of Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Iraq and the Gulf; of these, five serve food by chefs drawing from their upbringing or culinary experiences… in Israel.

MiddleEastMediLevantia in London was never inevitable. Yotam Ottolenghi arrived in London during the late 90s and recalls a city where “there wasn’t such a thing as an Israeli restaurant”. Until the 2010s, any restaurant that served Israeli food, such as Solly’s (1991-2014) in Golders Green, were anomalies and opened in neighbourhoods of northwest London (where Jewish people lived). They marketed themselves as one of the few places for London Jewry to eat ‘Israeli’ food. Solly’s was a cherished neighbourhood Jewish restaurant, its walls adorned with photos featuring the likes of Israeli spoon-bender Uri Geller and Jewish actress Maureen Lipman, a stark contrast to the largely non-Jewish clientele that has come to frequent the MiddleEastMediLevantian restaurants.

Where parts of Jewish culture in the UK have become mainstream, explicit Jewishness has not. In a talk for 2015’s Jewish Book Week, titled How London Fell in Love with Middle Eastern Food, Jay Rayner asked the panel guests – Itamar Srulovich, Tomer Amedi, Sarit Packer and Josh Katz (all, by now, familiar names on the MiddleEastMediLevantian restaurant scene) – whether Ottolenghi might have ‘released [the chefs and their restaurants] from the idea of Jewishness.’ It seems that in London (unlike America), when Jewish foods are ‘released from the idea of Jewishness’, they flourish. Yael Mejia used the anglicised (and distinctly un-Jewish) version of her name, Gail, when she opened her first bakery in 2005. Now there are over a hundred Gail’s’ across the UK, successfully selling bagels and slices of babka to delighted but unwitting gentiles. The Brass Rail at Selfridges sells a famous ‘New York-inspired salt beef sandwich with sauerkraut’. ‘New York-inspired’ (when not associated with the word ‘pizza’) is often code for ‘Ashkenazi Jewish’, in much the same way as ‘north London geek’ was used as a euphemism for former Labour party leader Ed Miliband’s Jewishness.

The success of these restaurants in mainstream British food culture also speaks to how British Jews’ taste in food is changing. The second and third generation Israelis who opened restaurants in London didn’t move to Israel; they were born there, which meant they didn’t buy into the nation-building project in the same way as their parents. Their relationship to Judaism is more ambivalent than those who owned the salt beef bars and delis of old; the food is more playful and expansive; they don’t keep kosher (many of these restaurants serve pork and shellfish); and they don’t feel the need to open in spaces where many of London’s Jews live. Eran Tibi remembers the frustration his Jewish friends expressed when he revealed his first restaurant would be in south London. “Why is there no parking?!”, they exclaimed, rallying against Tibi’s challenge to the usual pattern of Jews driving into familiar north London neighbourhoods to visit kosher and non-kosher Jewish restaurants. My Ashkenazi grandma, famed for her matzo ball soup, would be shocked to see how her son (my father) had become such a huge advocate of pomegranate molasses, a common component of many dishes popular amongst Mizrahi Jews.

Is there space in mainstream British culture for MiddleEastMediLevantian restaurants to be Jewish? Mainstream British culture has plenty of room for Jewish food outside of the restaurant - this month, Saturday Kitchen had an entire episode focused on foods to eat before and after Yom Kippur, with guests including Honey & Co.’s Srulovich and Packer, and former Palomar head chef Tomer Amedi. The Judaism (and Israeliness) of the chefs taking part was very much on display - it just isn’t an explicit part of their restaurants’ identities.

Rayner’s suggestion that Ottolenghi might have freed MiddleEastMediLevantian restaurants from their Jewishness is notable in a central London that has a vanishing amount of sit-down kosher restaurants. Bloom’s, when it closed in 2010, was unsympathetically described by Maureen Lipman as ‘stuck in a time warp’, adding ‘its [closure] has left a hole in Jewish food because Jewish restaurants now have become very Israeli and Lebanese in their cooking’. In one sense, Lipman is correct. Even Hyde Park-adjacent Tony Page @ Island Grill (one of the few central London kosher restaurants) promotes its “relaxed modern menu”, featuring dishes such as tuna tataki and dukkah spiced aubergine. Nowadays, the most renowned British Jewish restaurateurs (such as Berber & Q’s Josh Katz) are cooking “Israeli” food. Yet, nobody really thinks of these spaces, including their owners, as “Jewish Restaurants”. In Britain, unlike America, “Jewish Restaurants” only exist in Jewish neighbourhoods, frequented almost exclusively by Jewish clientele - where they are thriving.

Meanwhile, the popularity of MiddleEastMediLevantia and the decline of explicitly Jewish establishments, proves one thing: in central London, ambiguity sells. It seems we have all – even the dads angered by south London’s limited parking options – become citizens of MiddleEastMediLevantia.

Read more

What is British Jewish food, really? - The story of Jewish food in Britain

A guide to the best MiddleEastMediLevantian restaurants, and more

Credits

Josh Dell is a writer and editor focusing on food, wine and the weird. He has previously written for The Fence, Vice and WIRED UK.

Vittles British Jewish Food Week is edited by Molly Pepper Steemson, with additional editing from Jonathan Nunn and Adam Coghlan, and subediting by Sophie Whitehead and Liz Tray.

All illustrations are by Georgia Turner, a freelance illustrator and neuroscience PhD student from London.