Scam Patrol!

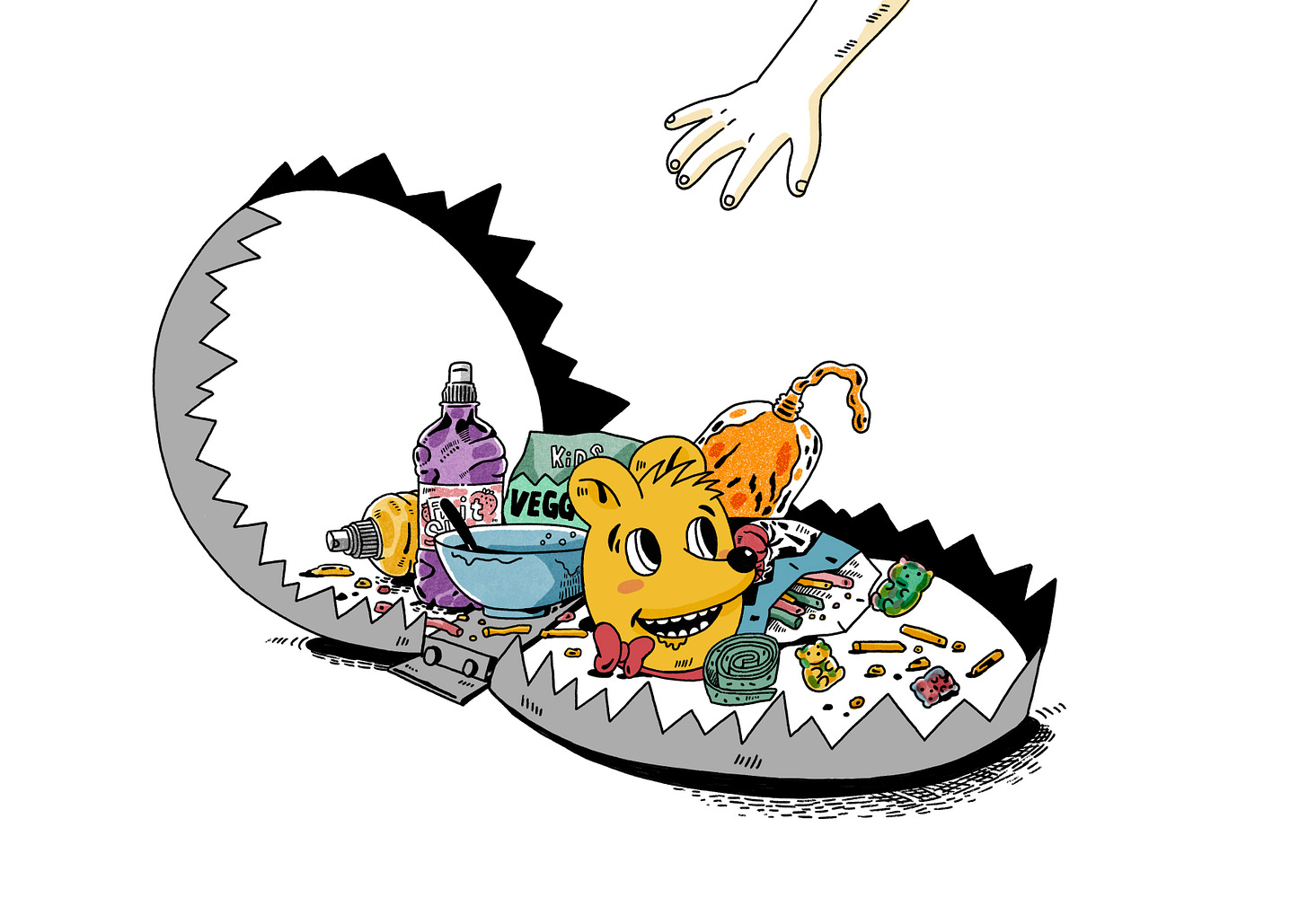

Which children's foods are scams? Tim Anderson finds his way through the kids’ food marketing maze. Illustration by Ming Yue.

Good morning, and welcome to Vittles Kids, a special series of features, essays, opinion and a guide about feeding children at home and in restaurants. In our last article of the series, Tim Anderson investigates the marketing maze surrounding children’s food, asking himself is this a scam? (and discovers that the biggest scam of all where he least expects it.)

A note from all of us at Vittles: it is impossible right now to think about the subject of food and children without also thinking about the forced starvation of children and adults in Gaza, as part of Israel’s ongoing genocide. There are many individual projects you can donate to, and we would encourage you to donate freely to those you know. The Sameer Project is currently raising funds for tents, food and water in north and south Gaza and you can donate via the links below.

Simply to exist in our unfettered free-market society is to be scammed, all the time, every day. We have to pay for water, which, famously, falls freely from mountaintops and the sky. If you’re a parent, you’re doubly scammed, because our kids constantly compel us to buy stuff that we know is a rip-off. Too often, by the time it occurs to me that I might be getting conned, it’s too late and I’ve already bought the thing. So, to try and become less of a chump, I’m investigating four suspicious phenomena in the world of kids’ food, to answer that nagging question: is this a scam?

CASE NO. 1: FRUIT SHOOTS

Allegations : Compared with squash in other formats, they’re a tremendous waste of money and plastic. And do they even contain fruit?

Imagine, if you will, a place called ‘Fruit Shoot Land ’. This is the kind of whimsical, abstract prompt that market researchers use in surveys and focus groups to understand how customers feel about their brands. When I asked my daughter what would be in Fruit Shoot Land, she answered ‘Fruit Shoots ’, which is correct, but weirdly, the drink itself didn’t even occur to me. I pictured bountiful orchards, birdsong on the breeze and children frolicking in sunlit uplands. And in the distance, an ominous plume of toxic smoke, from a burning landfill of plastic bottles and money.

Fruit Shoots are literally just squash, repackaged in small, child-friendly plastic squeeze bottles with instantly recognisable (and frequently imitated) labels bearing the colours of the fruit they represent: deep purple for blackcurrant, orange for, um, orange. They have a slightly goofy look to them that makes me think of 1990s ska bands. They’re fun – but they’re also way more expensive than just reconstituting the squash yourself. A 24-pack of Fruit Shoots costs about £7, so that’s 29p per serving, compared to around 5p per serving if you buy a bottle of double-strength Robinson’s. The price difference is far greater if you buy a Fruit Shoot at a cafe , where the price is usually more than £1. Plus, they produce a lot more plastic to contend with. (Recycling plastic is a diabolical, convoluted scam in and of itself.) But I keep buying them. Somehow, they’re a treat.

Kate Harvey, a psychologist in the University of Reading’s Kids’ Food Choices research group, thinks that the packaging is central to why Fruit Shoots are so irresistible – the bottle itself gives kids a feeling of autonomy. ‘Their size is perfect for a child,’ she notes, ‘and it’s more exciting for kids to have a little sucky thing that you can shut and open and chew, rather than just a little juice box with a straw.’

There’s a sucker born every minute – literally. The sucking reflex is powerful and innate, and remains a comfort well into childhood (see also: dummies, thumbs, pouches, etc ). Sucking on the nozzle of a Fruit Shoot could provide an additional layer of happiness to the already awesome experience of drinking squash.

But perhaps the most important reason why Fruit Shoots have such powerful appeal is that we give them that power. Tamara Vos, a mother of three and food stylist who has worked on numerous projects aimed at parents and kids, typically buys Fruit Shoots only for special occasions, like birthdays, or trips to the park on hot, sunny days. ‘But I don’t know how good that is,’ she says, ‘because then the kids see them as this incredible, unattainable thing.’ Setting Fruit Shoots aside for special days makes them almost as exciting as sweets or ice cream: the stuff of parties and playgrounds. Flipping the cap off a Fruit Shoot is the kids’ equivalent of popping a cork.

This is a power that boring old squash, made at home and carried with you in a water bottle – probably a little more dilute than Fruit Shoots, and tasting faintly of detergent – simply cannot possess.

VERDICT: NOT A SCAM. Sure, they’re poor value for money and bad for the environment. But they also absolutely serve their intended purpose.

CASE NO. 2: ANYTHING WITH A BEAR ON IT

Allegations : Food packaging with a cartoon bear on it is clearly aimed at children, and therefore inherently sus. What lies do those cheery faces conceal?

Haribo. Pom-Bears. Yoyos and Paws. My Favourite Bear. Barny. Bimbo. Hello Panda. Bears, everywhere! They may appear cute and cuddly, but remember: bears are ruthless predators.

The use of any cute animal characters on food packaging is controversial, to say the least. They’re a perennial target of Bite Back, a youth-fronted activist group that challenges the overwhelming presence of junk food advertising aimed at kids. Henry Makiwa, Bite Back’s head of communications, describes this presence as a ‘constant wallpaper’ and ‘an onslaught on the streets ’. Reading Bite Back’s research and listening to Makiwa rattle off the countless ways kids are exposed to advertising – on buses, billboards, Spotify and Instagram, to name a few – makes me realise these ads are so omnipresent that they may as well be broadcast directly into our dreams.

Most people would agree that advertising aimed at kids is problematic, but there isn’t much of a consensus on what specifically should be challenged. Case in point: Pom-Bears v Haribo. Both of them feature a smiling, rotund yellow bear on their label, but only Pom-Bears have run afoul of concerned consumers. They were named in a 2008 report by Which? on junk food targeted at children, and again in a 2021 ruling by the UK Advertising Standards Authority (ASA). Meanwhile, the Haribo bear runs free, with near-total impunity.

I emailed the ASA to ask them about why regulation regarding cute characters seems so inconsistent, and their response only made me more confused. They clarified that advertising using popular characters to promote junk food to kids is not allowed, citing rulings against a Swizzels ad featuring Scooby Doo, and a Cheestrings ad featuring Garfield – but the wacky Cheestrings mascot himself is OK. They also said they don’t regulate packaging, which is odd, because packaging is just advertising at point-blank range. In his book Ultra-Processed People, UPF cop Chris van Tulleken specifically calls out the Coco Pops monkey, but in the eyes of the law, that monkey is innocent.

How these products are apprehended is a matter of cultural common sense and personal perception. Haribo make few claims to be anything other than a sugary treat, so nobody thinks the Haribo bear is a threat. Pom-Bears do make some tilts at healthiness by proclaiming that they’re free from gluten and artificial colours or flavours. Personally, I have a lot more ire for Yoyos and Paws, the fruit leather products sold by Bear. Only 1% of strawberry Yoyos, for example, is actually strawberry; the rest is a mulch of apples and pears. Yoyos are spirals of deceit.

These days, industry bodies like the Food and Drink Federation have realised they have an image problem, and while they remain stubbornly opposed to meaningful change, they have learned to adjust their tone accordingly. But back in 2008, when the Which? report was published, they were far more brazen and unapologetic, claiming that cartoon characters bring ‘fun’ and ‘colour’ to supermarket shelves.

I have to admit, they have a point. What would the endgame of food label regulation look like? Should Pom-Bears and Haribo be packaged like cigarettes, in unappetising diarrhoea-brown cartons with macabre photos of body parts affected by metabolic syndrome? We probably don’t want to go there. But surely we do want brands to be upfront about what their products are made from, especially when they position themselves as healthy or natural. At least Tangfastics‘ main claim is simply that ‘Kids and adults love it so’. No scam detected.

VERDICT: SOMETIMES A SCAM. None of these bears are acting in your best interests, but at least the Haribo bear will give you exactly what you’ve bargained for.

CASE NO. 3: ‘VEGGIE’ SNACKS

Allegations : They contain insufficient veggies and can result in tooth decay, vomiting at the sight of real food, and developmental delays.

Kids’ snacks with ‘veggie’ in their names often contain negligible amounts of actual veggies. I buy a particular brand of pesto-flavoured veggie cakes, because they’re amenable to my son’s allergies and they feel healthier than conventional crisps or crackers. They’re 76% lentils, which seems pretty good. But are lentils even veggies? And more to the point, are they still nutritious after they’ve been puffed, pressed and powdered with deliciously salty pesto seasoning?

They seem wholesome, but perhaps only in comparison with other veggie straw products from the kids' aisle, which are mostly extruded potato and rice flour or similar starches. I asked Harvey if snacks like these might at least have some redeeming value by encouraging self-feeding (as they claim), or by getting kids on board with the flavour or even the concept of vegetables. ‘They’re probably not doing them much harm,’ she says, ‘but it absolutely won’t familiarise children with vegetables, which is ultimately what you want.’

Harvey points out that veggie straws and things like baby food pouches differ from the other products discussed in that they’re designed to appeal to parents, rather than kids. Their packaging is more subdued, with lots of greens and oranges: an ‘eat the rainbow’ palette to convey a sense of earthy goodness. But the disparity between the wholesome image of these products and their actual nutritional value has come under increased scrutiny, prompting Bee Wilson to ask in the Guardian: ‘Are toddler snacks one of the great food scandals of our time?’

This ongoing ‘scandal’ has made many parents feel pretty freaked out about pre-packaged food for babies and toddlers. Wilson’s article, which became something of a flashpoint in the baby snack discourse, claims (without evidence, mind) that ‘these snacks – organic or not – are one of the reasons that many infants have not learned to chew properly ’. Wilson reported that one of her primary informants, a veteran nursery manager, told her that ‘there has been a “massive increase” in toddlers with tooth decay, as well as a rise in the number of children reaching the age of three who are more or less nonverbal. She attributes this speech delay to the fact that the skills and muscles needed for chewing are related to those needed for speech.’

Never mind the implosion of the NHS and worsening social determinants of health in an age of increasing wealth inequality – that couldn’t be what’s exacerbating developmental and dental problems among children. No, the reason your kids have cavities and are struggling to talk is because you gave them too many melty sticks. Shame on you!

Clearly, the article touched a nerve, and it has prompted rebuttals arguing for a more holistic understanding of why children’s health may be faltering, and that parents shouldn’t be tasked with personally correcting for huge systemic problems. Nutritionist Laura Thomas points out that ‘accounts of a nefarious food system, however carefully constructed to avoid blaming individuals, virtually always hinge on changing individual behaviour ’. She adds that this pressure hits poorer mothers particularly hard, as they’re already more affected by classist and racist judgments about their ability to parent.

I won’t defend veggie straws outright, because I do think they’re a scam, and it makes me feel like a shill for the food industry. They’re not a substitute for actual vegetables, and they shouldn’t be presented as such. But I will say that every child I know who ate veggie straws as a baby – which is all of them – have wound up with totally different, individualised food preferences and eating behaviours as they’ve grown up. As Laura Thomas put it, ‘You can do everything by the book and still have a child who’d rather mainline Biscoff spread than sweet potatoes.’

VERDICT: DOUBLE SCAM. The snacks themselves are definitely a scam – but so is the moral panic about them.

CASE NO. 4: HOME-COOKED MEALS

Allegations : Home-cooked meals are positioned as the gold standard for familial harmony, nutrition and cultural preservation … but is it really that simple ?

With convenience come hidden costs and unintended consequences – but convenience itself isn’t a scam. In fact, convenience is a virtue. Convenience frees up time for, you know, life. Which brings us to one of the most insidious scams of all: home-cooked meals.

I am, of course, absolutely in favour of home cooking. Meals prepared and enjoyed at home can be nutritionally sound, socially nurturing and reassuring to both kids and parents, because we can see exactly what’s in them. But the fact that family mealtimes are often anything but happy, warm and cosy is well documented. As Harvey explains, ‘The primary goal that parents have in their heads when planning a meal is to avoid conflict.’ This rings very true. I also use home-cooked meals to ease the pain of conflicts past, as a peace offering or an act of penance, seeking absolution for parental sins of wrath and pride: buttery, garlicky prawn pasta after losing my shit during a struggle on the changing table, or a simple snack plate of fruit, carrots, ham and crackers upon realising that I was the asshole in an altercation with my daughter.

But these edible atonements don’t always work, and there are few things more demoralising than making something you’re so sure your kids will like, only for them to contort their face into an exaggerated grimace and say those four dreadful words: ‘I don’t like this.’ But last week you loved miso soup – and now you’re literally throwing it on the floor?! WTF. Home cooking is a thankless, Sisyphean task – and it’s unpaid labour.

As Laura Thomas writes, capitalism is ‘contingent on the gendered exploitation of unpaid and undervalued care work … producing purées from a bag of sweet potatoes is only cheaper than a pouch because we have erased the labour that goes into producing it ’. If we really want to give parents (read: mothers) the freedom and flexibility to make their own sweet potato purée, we need an economic system that allows for it – something like a universal basic income (as a start).

One could argue that home cooking also has value beyond nutrition and the labour that goes into it, and many of us put a lot of faith in the sociocultural significance of cooking and its ability to form intergenerational bonds. But love and affection aren’t always conveyed through homemade food – and neither is culture itself.

Shaan Mahrotri, a food industry friend who also handles the home cooking, told me of his frustrations that his daughters are just not into the Indian food he grew up eating. Dal in particular is a sore spot. ‘We’re brown,’ Mahrotri says, exasperated. ‘This is supposed to be in your DNA!’ Vos, who spent her early years in Kyoto, tells a similar story of food culture interrupted; her Japanese mother is appalled by her grandchildren’s food preferences here in the UK, which are very different from what children are expected to enjoy in Japan. ‘The nurseries there are hell-bent on giving very balanced meals,’ Vos explains; an appreciation for a wide variety of whole foods is instilled at an early age, reinforced by a kind of positive peer pressure among the kids themselves.

Food is culture, but culture doesn’t follow a neat, linear path from the kitchen to the table. It isn’t just whatever mama bird regurgitates for us. We’re more like filter-feeders, taking in a bit of everything that floats our way. Sometimes we get a parasite, sometimes we get a pearl. But mostly we just get a lot of random crap that we have to sift through. As parents, all we can do is help with the sifting.

Of course, home cooking can influence our kids’ food choices, but that’s probably more about how much time we spend at the table, not how much time we spend in the kitchen.

But that’s the thing: we just don’t have enough time. We’re all too busy, sprinting eternally on the hamster wheel of capitalism – which is, of course, the biggest scam of all.

VERDICT: SORT OF A SCAM. Home-cooked meals aren’t necessarily a scam – but the expectations that surround them are.

Tamara Vos is a colleague of the author and one of Vittles’ resident recipe testers.

This essay is part of our supplement Vittles Kids and is best read on our website here. To read the rest of the series, please click below:

‘That must be hard’, by Laura Goodman

The things I cook for work...and what my children actually eat, by Rukmini Iyer

'You need to make less pasta and more rice', by Ishita DasGupta

Rukmini Iyer's Magical Children's Party Recipes, by Rukmini Iyer

The Vittles Kids London Restaurant Guide, by various.

Credits

Tim Anderson is a Wisconsin-born writer specialising in Japanese cookery. He has published nine books, including Ramen Forever, Your Home Izakaya, and Hokkaido. He also writes about American food culture at 24hourpancakepeople.substack.com. He currently lives in Lee with his wife, two children, and FIV-positive cat, Baloo.

Ming Yue is a comic artist and illustrator from Beijing. She spent several years living studying and working in Japan, which left a lasting mark on her creative work. Later driven by a curiosity about different cultures and ways of life, she moved to Belgium. Her work has been exhibited in China, Japan and across Europe, and you’ll spot her comics and illustrations in all sorts of publications.

This supplement was subedited by Tom Hughes, Sophie Whitehead and Liz Tray. The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

I would definitely add 'hidden veg' into this list. Not veggie snacks, but the idea that you have to hide vegetables in otherwise unsuspecting food to get kids to eat it. I have known friends make pasta sauce which is basically a puree of 12 vegetables, and congratulate themselves on their healthy choices. But their kids are mistrustful of anything that looks like a vegetable if it isn't a cucumber stick.

It's hardly engendering better ways of choosing if you communicate that vegetables are so horrible that you have to hide them away. Spag bol that is 50% courgette is revolting, child or adult.

Thank you for a fascinating read!! There's one huge domestic-labour-tastic advantage to Fruit Shoots: they spill less. If you're having a party or playdate, make a lovely big 1950s housewife pitcher of squash, let the children pour it themselves Montessori-style, then wander off with the cups, you are looking at multiple squash spills, some of which will probably only reveal themselves after the wasps find them 😭

Unless the bottle is full (unlikely, because as you mention they hoover them) the sucky cap keeps it all contained. Even if they do leak, it's less drama than a full cup of squash going everywhere.

I recycle, ride a cargo bike, and avoid flying and fast fashion. But the second another child is visiting my home, it's Fruit Shoot time.