'That must be hard'

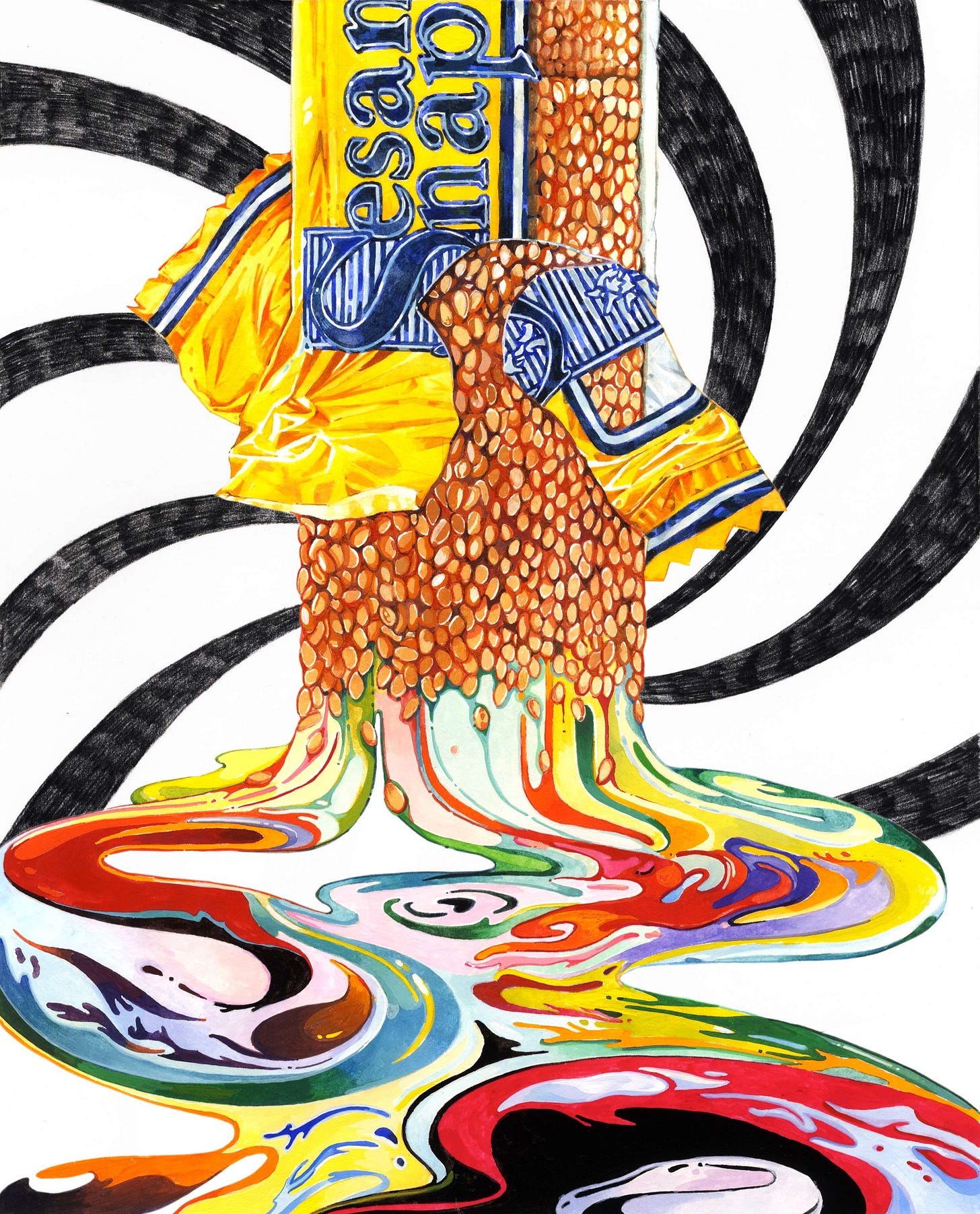

Laura Goodman on raising children with allergies. Illustration by Sing Yun Lee.

Welcome to Vittles Kids, a special series of features, essays, opinion and a guide about feeding children at home and in restaurants. Today’s essay by Laura Goodman is a deeply moving and darkly funny account of raising children with serious allergies (once she and the medical establishment had managed to find out what they were).

A note from all of us at Vittles: it is impossible right now to think about the subject of food and children without also thinking about the forced starvation of children and adults in Gaza, as part of Israel’s ongoing genocide. There are many individual projects you can donate to, and we would encourage you to donate freely to those you know. The Sameer Project is currently raising funds for tents, food and water in north and south Gaza and you can donate via the links below.

The number of new food allergy cases doubled between 2008 and 2018, and the sharpest increase was in young children. Still, I would describe our collective attitude to allergies as dismissive (at best) and scathing (at worst). This is thanks in part to many decades of demonising food groups, which muddies the waters between mortal danger and bloating, and a deep-rooted belief that allergies exist in the realm of the neurotic. (The possible reasons for the increase in childhood food allergies are myriad and complex – and summarised nicely by scientists in this episode of Gastropod.)

As an allergy parent who writes, but who has barely dared write on this topic, it’s the hypervigilance – the way there is always something allergy-related to think about – I find myself most eager to share. It’s the thing that occasionally separates me from the parents around me, who (lovingly) pass me ingredients labels to check because they don’t know how to read them like I do, and who say ‘That must be hard’ and mean it, but don’t know the half of it.

I wanted to try to paint a picture for you, but I had to delve into some weary recesses of my mind to find the material, so what I’ve written is more of a collage.

1.

‘Have you tried football hold?’ A kind woman has entered my house to help me breastfeed, because we’re struggling. I am weeks in, bleeding all over the sofa. I’m shrunken by my interactions with professionals, so the woman’s kindness is a relief, but now I feel like I’m letting her down, too. ‘Relax!’ she says. ‘Don’t think about it!’ My failing body finds itself stiff but reclined, randomly angled. The kind woman coaxes the baby – Z – to the correct position, even though she insists the baby can and will find the nipple herself if I relax enough. I do not believe for one second that relaxation or football hold can fix us.

2.

I don’t know Dr O, but I’ve seen him being jolly in the waiting room, parading babies around like this is his courtyard and these are his cherubs, making jokes about which football teams the babies will support. I suspect Dr O hates the mums, though, and I’m right.

He is leaning back in his chair with his feet crossed on his desk, eyes fixed on his computer screen. It’s a stance I know well from when I did work experience in newsrooms around the time of the financial crisis in 2008, when I still believed journalism careers were available to normal people.

‘What is it you don’t understand, Laura?’

He clicks his mouse, does not look at me. He’s Tony Montana and I’m responsible for some unknown betrayal, but instead of mountains of cocaine there are Bristol Stool Charts and blood pressure monitors, because this is a doctor’s surgery and this man has a duty of care.

Z is being sick fifty to sixty times a day, and over the weekend we’d become so panicked by the volume of vomit we’d taken her to A&E. The doctor is annoyed because as far as he’s concerned Z has a bit of reflux and he’s already told me that; he’s received word that I attended A&E and has taken my ‘ticket’ as a stain on his excellence.

That same afternoon, at a clinic, Z doesn’t weigh enough and a new health visitor cocks her head to the side and asks me why I think that might be.

The only sane way to deal with what is happening to me is to go mad, and that process is well underway. I become aware that my child’s suffering is my fault – that I’m in a race against everyone and everything to determine what it is I’m eating that’s making her sick. I do not even have time to process the strange newness of this relationship between our digestive systems. The doctor says: It’s nothing to do with your milk, that’s impossible.

3.

A kind friend brings me some food and the friend is Meera Sodha and the time is around the publication of her book, East. Lunch is her sprout nasi goreng, which she describes in her Guardian column as “smothered in unami-ific sauces”. I’ve given up dairy by this point and the vomiting has eased, but soon after eating the sprouts, there is a sick so large and violent that Z and I both wail inconsolably. I cut out soy. Within two weeks, the vomiting completely stops. It’s nothing to do with your milk, that’s impossible.

4.

It’s easier to move around the world when your baby isn’t in a permanently soggy muslin fortress, so I start doing a bit of living. At a baby group, a woman tells me that for a little while she’d thought her baby had a dairy allergy, ‘but actually she’d had an earache!’ My brain starts swilling around in my head and I picture myself falling backwards into a hole, making sure to cushion Z’s fall with my own body. Contrary to popular opinion, the company of other parents isn’t ‘just what I need’. If we’re in the same boat, the leak is not affecting us equally. I wade home through treacle, or colostrum – something sticky. That must be hard.

5.

I love food and know what’s in things, so I’m confident at weaning and we’re having fun. Among the things Z loves are eggs, noodles, avocado, pickles, aubergine, peanut butter, okonomiyaki, shepherd’s pie and pancakes, and her chubby wrists have that invisible rubber band effect. Nonetheless, I’m locked into the NHS’s outdated, clunky programme for young allergics and must see a dietitian. The dietitian recommends Bird’s custard powder. She’s very proud to have noticed that if you make it with an alternative milk, it’s dairy-free. I nod and leave, clutching print-outs, for I must bravely proceed to the first rung of the milk ladder.

The iMAP milk ladder is the day-to-day work of a less severe allergy. It’s a series of steps, designed to gradually increase tolerance – small amounts of milk powder baked into a biscuit, followed by whole milk baked into a muffin, followed by whole milk in a pancake, and so on. It’s now a well-trodden path for people with a moderate milk allergy, but it doesn’t exist in the same way for all food allergies (as I’ll find out later, no spoilers!). Doing the ladder is just another task – like packing a bag for gymnastics, doing phonics homework or putting LEGO away – only it involves a) baking b) precision and c) observing your child as you would a science experiment: her eczema, her level of comfort, her shit. Every day, the milk ladder says: You alone have the power to get her over it – are you doing enough?

I spend many an hour grappling with quantities, finding ways to bake milk powder into edible items. Someone on YouTube recommends buying Garibaldi or Malted Milk biscuits instead, which is the sanest thing I’ve heard for months.

As for the Bird’s custard: I don’t like it, so I don’t buy it. I’m starting to remember that you can ignore people.

6.

We have a second perfect baby – G. And urgh, she isn’t gaining weight quickly enough. I’m feeding round the clock in a bid to escape the midwives’ clutches. My understanding is that to survive in this town, you need to shake off the medical professionals. GPs and health visitors know little about allergies. In my experience, they will say ‘It’s probably not that’ in the face of itchy, writhing evidence. I toy with a state of denial as G settles into a life of bleeding eczema, congested breathing and vomiting, but eventually, the round-the-clock screaming plummets us into the darkness. She is not comfortable in her body.

The nights are ear-splitting and gruelling; Rich and I pass G between us, staring at each other, despairing. We sleep in thirty-minute bursts for months on end and are zombified by day. One afternoon, I go out for dill and come back without it. Rich goes to the shop and asks if his wife left her dill on the counter. The guy says, No, your wife definitely took her dill! He plays his CCTV footage and there I am, paying for the dill and then grimly, mechanically putting it in my coat pocket. Another night, the crying is so guttural, so continuous, so bleak, that after four hours, we start to worry. Is something different going on tonight? We dial 999 and get an automated message. Eventually, we all fall asleep.

7.

We’ve established that G is allergic to milk, egg and soy. We’re weaning her early as per the advice of our consultant and I’m keen as mustard (one of the top fourteen allergens) to work swiftly through the other big names – rule them out, if you will. I mix a little tahini in some courgette puree and forty minutes later there are six paramedics standing in our living room, just as Z returns from nursery. I am firing off deranged messages from the ambulance and my friend Janet (not a zombie) says, Oh shit, remember last Sunday she was really bad? We’d eaten hummus the day before.

8.

The allergy clinic is a mind-melting beast I could not hope to summarise here (I would lose you instantly; I tend only to share the details with my internet friend, fellow allergy mum Amanda, whom I’ve never met). But rest assured we’ve been through several rounds of pinprick tests and blood tests before we are summoned for a sesame challenge. At a ‘challenge’, the child must eat their allergen in increasing amounts every twenty minutes to see what happens. One consultant keeps repeating that it’s the ‘gold standard test!’, which is a bonkers thing to say, but demonstrates the inefficacy of the actual tests we have available in 2025. As requested, we pack our own Sesame Snaps (four packets) and arrive at 8am on a Sunday. An older boy opposite us is with his dad to check if he’s still allergic to octopus; they’ve brought their own Brindisa octopus tentacles, steamed in their own juice. Quite quickly, his mouth starts to itch.

Janet (the friend that’s not a zombie) has come with us and she is saying to me, We know what’s going to happen, Laura, she’s not going to get past the first dose. And I think it’s interesting Janet is so sure about that, because the soup of medical lunacy I’ve been sipping has led me to believe that maybe I’ve made all this up and G is actually not allergic to anything.

For some reason, we are instructed to skip dose one (lip challenge) and go straight to dose two (0.5g of the specified food). G eats it and is fine, but I can see some reddening on her face; I hear myself pointing it out and decide I’m probably being neurotic. After twenty minutes, it’s time for dose three and G is refusing it, which is annoying. Of course she’s refusing it, because sensations are occurring in her mouth and throat that she’s too young to articulate, and soon enough a tidal wave of vomit splats us all and she is covered top to toe in hives. She’s given an antihistamine and we’re told to settle in for a period of observation. Now dressed only in a nappy and a hospital gown with rainbows on, she does a poo. I go to change her and see that a new red rash has covered the top half of her body, almost as though it’s tracking the 0.5g of sesame’s journey through her digestive system.

I ask for the consultant to come and see her, and stand her up for his inspection. He is lovely, but visibly alarmed and horribly sorry. G’s test results (pinpricks and bloods) were not in line with this reaction. He holds his chin in his hand and shakes his head, muttering, ‘Only 0.5g … But she’s not allergic … No ... She had a small pinprick ... It was just the first dose … This shouldn’t happen’. Janet, not a zombie, an angel, says, ‘But it has happened’. And after a while, sombrely, he concedes: ‘This child is allergic to sesame.’

9.

‘I tried the hummus, mama!’ comes a cheery shout from another room. Fear not, it’s Z, the big one, not allergic to sesame, just unsure about dips as a concept. The neighbours have invited us for Christmas drinks and I rush to the table to check G hasn’t had any. A vision of all the party buffets ahead of us stretches before me. I think about the double-page spread in my first book, Carbs – an abundant spectacle featuring lime pickle cheese straws, corn nachos, loaded potato skins, cocktails with umbrellas and stripy paper bags of sesame snap popcorn spilling across the table. Now it’s giving anaphylaxis.

10.

G is two and has recently started sitting still to watch TV for brief periods which means I can do some emails while I make dinner, for a treat. An email comes in from an organisation that provides care for my children.

REMINDER: WE ARE NUT FREE

This is a gentle reminder that we aim to keep a nut-free environment. This applies to all snacks. Children who suffer from nut allergies can develop a severe, potentially life-threatening allergic reaction.

Recently, we have noticed some children bringing in sandwiches made with seeded type breads, which fall under the same category.

I start to sweat and my breathing is erratic. I’m going to be quite specific about why. As I mentioned earlier, there are fourteen allergens recognised in the UK as the most common ingredients to cause allergic reactions. Here they are, in bold as you find them on ingredient labels: celery, cereals containing gluten, crustaceans, eggs, fish, lupin, milk, molluscs, mustard, peanuts, sesame, soybeans, sulphur dioxide and sulphites and tree nuts.

The most common cause of fatal anaphylaxis in school-age children is cow’s milk, not nuts. None of the allergy charities recommend nut bans ‘because they are very difficult to enforce and can lead to a false sense of security’ (Anaphylaxis UK) – the false sense of security is illustrated beautifully in the email by the words ‘aim to keep’. The bit about ‘seeded type’ breads falling under ‘the same category’ is scary to me in its vagueness. What constitutes a seeded type bread? A linseed loaf or a burger bun? Both? Are seeds banned then? Which ones? Where might parents find them? Sesame seeds are slippery little bastards, often hidden in plain sight, and parents of non-allergic children have no reason to keep tabs on them.

My brain churns through all of the above and more. And then I baste the chicken, while Wallace and Gromit eat Wensleydale in the background. G approaches the counter in that antsy, nibbly pre-dinner mood. She picks up an oatcake: Got egg in it, mama?

11.

There’s nothing in the fridge. Rich is wondering what he can cobble together in the next hour or so – something nuggety or peanut buttery. He says, Imagine if we could give them both an omelette? Or macaroni cheese? I did always imagine my kids would eat a lot of macaroni cheese. I think this is the bit people think must be hard. This is the bit I hardly ever think about.

This essay is part of our supplement Vittles Kids and is best read on our website here. To read the rest of the series, please click below:

The things I cook for work...and what my children actually eat, by Rukmini Iyer

Scam Patrol!, by Tim Anderson

'You need to make less pasta and more rice', by Ishita DasGupta

Rukmini Iyer's Magical Children's Party Recipes, by Rukmini Iyer

The Vittles Kids London Restaurant Guide, by various.

Credits

Laura Goodman is a writer based in Walthamstow. Her Substack is taking a break but will be back with a bang when the kids go back to school.

Sing Yun Lee is an artist and illustrator based in Essex who specialises in painting, drawing, and collage. You can find more of her work on her website and on her Instagram.

This supplement was subedited by Tom Hughes, Sophie Whitehead and Liz Tray. The full Vittles masthead can be found here.

I'm mother to a Laura who was fed cow formula by a well-meaning midwife. My baby was only four days old. Within hours Laura was covered in eczema. I'd made it clear my baby was to receive only my milk because of our family history of allergies but I was 21 years old and it was 1988 so nobody took me seriously.

I had to be weaned at six weeks old because I 'failed to thrive' on formula. This was 1966. Allergies 'didn't exist' then. I was a fussy crying baby who just about tolerated boiled goats milk until I didn't and had to be fed a watered down pablum. Milk, yogurt and cream still upset my stomach badly although I break down and eat ice cream, suffering the consequences. My daughter cannot eat dairy to this day.

Over the last ten years I've gone on to develop allergies to bee and wasp stings ( anaphylaxis), and some kinds of fish ( itchy mouth, vomming). It's been an 'interesting' experience because it took me a year to be taken seriously re my fish reaction despite swelling up like a bloody puffer fish after eating some. This is why I cried on an Easyjet flight when the crew made a tannoy announcement to say they had a toddler on board with severe allergies and could everyone not eat food unless it had been supplied by the flight attendants. Not one person complained. For once, humans didn't disappoint me.

Lots of love to you x

Everyone needs a Janet.