Good morning and welcome to Vittles! As it’s a bank holiday in the UK, we’re taking a day off from publishing new content. Instead, to keep you occupied, we’ve compiled a reading list of some of our favourite archive pieces from ‘The Hater’, our column purely dedicated to the art of hating. For the next few days, last year’s essays will be available to read for free: from Ruby Tandoh on The TV Food Man and Sheena Patel on Rich People Peasantcore, to Tom Usher on the phenomenon of Norman’s-hatred and at least two articles on why Americans are annoying about food. The column will return next Monday with Simran Hans on a certain food podcast we’ve all been listening to.

If you wish to receive Vittles Recipes on Wednesday and Vittles Restaurants on Friday for £5 a month, or £45 a year, then please subscribe below – each subscription helps us pay writers fairly and gives you access to our entire back catalogue.

10 pieces from ‘The Hater’ unpaywalled for the Summer Bank Holiday

A biography of the TV Food Man, by a person who hates him

It is hard to describe TV Food Man’s approach to cooking by reference to anything in the food itself; this is not a style of cooking, because that would mean looking at some facet of the cooking or the culinary heritage, when what is really important in all of this is him. A lasagne is rolled-up shirt sleeves, a look to camera, a summary clapping of hands, tea towel thrown over a shoulder, shouting over the noise of the food processor, Right!, striding without purpose, bish bash bosh, a white nose now pink with sunburn, throwing utensils into the air and catching them again, flirting with a woman who is trying to pipe meringue, Just go and ask your local butcher, chopping very quickly, talking loudly at people who are trying to explain how corn is grown, jeans that are either too large or very much too small, throwing things into saucepans from a height, The Thai are a beautiful people, pretending never to have heard of tinned salmon, big hands doing things badly but with absolute confidence.

Why has austerity become the new rich person aesthetic?

Why are these Influencers pretending that they themselves till the land and eat like seventeenth-century French peasants when in fact their chopping boards cost more than most people’s rent? I’d prefer rich people to be ostentatious and unapologetic, not try to ape simplicity. When I was a child, I was fascinated by the stories of the banquets of Henry VIII, where birds like swans and peacocks were served cooked then presented with their feathers reattached as if they were still alive and only Hezza was allowed a fork for the sweet courses, forks not being used by regular-shmegular person until a century later. The cooks used sugar and spices from China, Africa and India to signify wealth, status, except these spices do not mean those things now. The less-is-more aesthetic, the austerity on the plate, is what confers status, just as bright colour or patterns do not mean status and wealth like they used to. The denying oneself of exuberance, of too much, is now what means you’re wealthy. Now a curry would never mean you’re rich, not the way a huge single ricotta on a plate means not only wealth but taste, attainability and arousal.

Is Norman’s really the front line of gentrification, or just an innocent cafe we love to hate?

But this is the confusing thing: the vibe was me. If you said ‘Tom, would you like a place that plays 90s hip hop, sells your favourite hot sauce, serves food you love and has fantastic long reads about modern masculinity available to read as you do so?’ I would reply, ‘Hell yes brother, let me just put on my Carhartt beanie.’ But this is the exact reason that it made me feel so uncomfortable, and why it makes a lot of people who look like me feel uncomfortable. Because, like most middle-class people, I hate people like me, people who are acutely aware of gentrification from an ethical standpoint, but love the fact that they can easily access pints of Beavertown.

Americans thinking everywhere should be like America, part 1

Obviously I don’t hate tacos. I don’t think it is even possible to hate tacos – they are a blameless and delicious handheld carb vessel for stewed and grilled foods. But there is a particular type of taco snobbery that I find more insufferable than watching someone using a fork to eat taco filling out of a hand-pressed tortilla. It’s not just that it’s now possible to find good tacos in London, from places like La Chingada in Surrey Quays or Sonora in Stoke Newington. My gripe with taco snobbery, especially when it comes from Americans abroad, is that it showcases an attitude that assumes the American experience should be replicated around the world, while forgetting that respect for Mexican food, especially in the US, has been hard-fought.

Americans thinking everywhere should be like America, part 2

The problem is that Americans, for the most part, are a uniquely insular, incurious people, with the British taking second place. Perhaps when you create much of the world’s mainstream culture and entertainment – not to mention foreign policy – you begin to believe that your experience is the barometer by which every other experience should be measured. It’s a mentality that causes Americans to go to ‘Europe’ and give Italian trattorias bad Google reviews because they didn’t have chicken alfredo, and because a single portion wasn’t large enough to feed a family of four.

The anxiety of gut health apps, ZOE, and the culture of perpetual debunking.

But there’s something about ZOE, along with the broader preoccupation with gut health, that I find troubling. The sheer specificity of it, the level of self-surveillance, management and monitoring that it demands, the expectation that we should achieve such a heightened level of expertise regarding our own bodies – none of this strikes me as realistic or desirable. While ZOE critiques calorie-counting, its programme seems to encourage more elaborate forms of restrictive eating, new taxonomies of good and bad food, and fresh opportunities for self-castigation. Where once you might have fretted over eating too many biscuits, now you can worry about failing to maximise the ‘microbial diversity’ in your gut. Even the most mundane consumer choices are suddenly made fraught and high-stakes. The questions posed on ZOE’s website have the same urgent, neurotic tone as a late-night session spent googling symptoms: can turmeric supplements damage your liver? What’s the best natural sugar substitute? Are nuts bad for you? Should you be juicing your fruit and vegetables? Can bread be healthy? Is coffee healthy? Can alcohol be healthy? Did dinosaurs have gut bacteria? Is ultra-processed food hiding in your fridge?

The unhelpful binarisation of food

UPFs are the latest supervillain of the nutrition world. They have been linked to cancer, heart disease, high blood pressure, metabolic syndrome, depression, irritable bowel syndrome, adolescent asthma and wheezing, frailty, and increased risk of premature death. What’s more, they’re ubiquitous in our food supply, making up around 56.8% of the UK diet, while as recently as last week, The Guardian asked ‘why are 1 in 7 of us addicted to ultra processed foods?. As a nutritionist whose MO is to help people feel less afraid of food, I’ve seen the ways UPF discourse has heightened our fear and anxiety over the fundamental act of nourishing ourselves. What seems like a new frontier in nutritional sciences is really just a variation on the theme of dichotomising foods into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ and reinforcing arbitrary binaries.

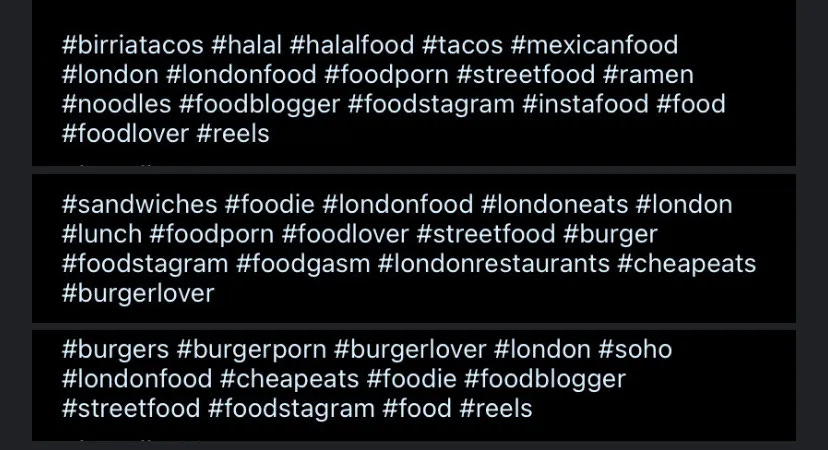

How the apps increasingly shape the way we eat

Ultimately, the SEO-ification of food seeks to prohibit the magic of the everyday encounter: the very event-ness of food. It removes the food from the social, erases the complexity of human histories and interactions that create foodways in the first place. What scares me isn’t just that being online mimics the experience of walking through a bad shopping centre. It’s that, if we continually feed the algorithm and respond to what it spits back out, then let it train itself on our responses, we will be left with barely any genuinely human content for the algorithm to parse. Even my copywriting work is now under threat, as ChatGPT can effortlessly churn out the same dirge in a fraction of the time. Soon machines will be writing for machines.

The tyranny of the median customer

Curation can be, at its best, a way of bringing things unexpected together that might never have been grouped with each other – as happens in good exhibitions, or good parties. But urban curation, practised by a small group of very similar people, is doing the exact opposite. It is arguably giving many people what they want, but by deciding top-down what is sellable and what isn’t, by trying to please everyone, what is left is a kind of odd homogenisation, an attempt to find the exact centre point on a spectrum of taste that doesn’t exist, cutting off and cauterising possibility, rewarding generalists and shunning specialisms, leaving an impoverished vision of what people actually love. What remains is far worse than the curated offerings of any music festival: it is focus-grouped food.

What is wrong with the London restaurant scene, and how can we fix it?

This could never have happened in London because British restaurateurs are preoccupied with image, appearance, style – the customer pays for the hefty loans taken out to give a dining room a particular look (which for many years derived from Julyan Wickham’s design for Kensington Place). The same restaurateurs tend to illiteracy. They mangle language and can’t punctuate. They are also pervious to crazes. In comparison to Paris, Vienna, Zurich, London restaurants have a short life. They are slaves to neophilia. This week tieles, next week 24-hour slow-cooked guttersnipe.

But the real problem with restaurants is not confined to restaurants… Britain is fucked. Only a bloody revolution will bridge the chasm between the indecently rich and the struggling majority. Jonathan Meades

The full Vittles masthead can be found here.