Who is Chinatown for?

Xiao Ma unpacks the layers of London’s Chinatown. Illustration by Kenn Lam.

Good morning, and welcome to the Vittles Chinatowns Project. In this essay, Xiao Ma explores how London’s Chinatown has evolved over the years and its continued resonance and importance for various communities despite rebranding, gentrification and commodification.

You can read the rest of the project here:

The New Chinatowns, by Barclay Bram

Crying in Wing Yip, by various

The Vittles Guide to London’s Chinatowns, by various

The Vittles Guide to the UK’s Chinatowns (including individual guides to Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Cambridge and Glasgow), by various

I first stumbled into London’s Chinatown by accident when I moved to the UK twelve years ago. As someone who grew up in north-west China, I remember feeling out of place beneath the red lanterns, surrounded by signs that seemed frozen in time and the scent of roast duck. But within a few years, Chinatown would become my workplace: in 2018, I began leading walking tours that shared the area’s hidden histories with visitors as part of Chinatown heritage projects led by China Exchange.

On these walks, I always ask people what comes to mind when they hear the word ‘Chinatown’ and generally get some variation on ‘a place dedicated to/celebrating Chinese culture’ as a response. One day, I tried a thought experiment with a school group from Wales: I asked them what a ‘Wales Town’ in Japan would involve.

‘The Welsh dragon’, ‘Welsh cakes’, ‘Daffodils’, ‘Our flag’ came the shouted responses.

But when I asked if any of these things represented them as people, they said no. ‘So, should we conflate Chinatown with Chinese people and culture?’ I asked.

Many visitors to London’s Chinatown speak of the place confidently, as if it were a standardised product – predictable and ready-made, like a familiar menu item. But the view that Chinatowns are timeless spaces with a homogeneous identity has been shaped by over a century of racialised and romanticised portrayals in media and literature, as well as modern urban branding that markets Chinatown as a cultural product. The social production of Chinatown is partly shaped by the racialised construction of Chineseness in the UK – and, in turn, an established Chinatown informs the dominant imaginaries of Chineseness in Britain. That’s why I hesitate when any urban space with traces of Chinese presence is labelled a Chinatown. The name carries history and weight.

The functions and meanings of Chinatown for London’s Chinese diaspora have continually evolved. For many post-war migrants who arrived before the 1980s from former British colonies – like my in-laws – Chinatown was the first point of connection. It offered work through local community networks, food and groceries from home, and even cinemas screening Cantonese films. That era has passed. Chinese restaurants and supermarkets have long since proliferated across London, meaning that trips to Central are no longer a necessity, while family-run Cantonese restaurants have slowly given way to bubble tea joints and trendy regional spots serving Sichuanese or Xi’an food.

‘But the view that Chinatowns are timeless spaces with a homogeneous identity has been shaped by over a century of racialised and romanticised portrayals in media and literature, as well as modern urban branding that markets Chinatown as a cultural product.’

At the same time, Chinatown has never belonged only to Chinese Londoners; it has always been shaped by London and the people within it. That influence has grown massively in recent years, and the area has become an increasingly popular tourist attraction – the TikTok Chinatown. Like any place, Chinatown doesn’t hold a fixed identity. Multiple Chinatowns exist at once, layered with overlapping or conflicting histories and stories. For many of the second-generation British-Chinese people I’ve spoken to, Chinatown is both a time capsule and a shifting tide – people return to make new memories or revisit old ones. Still, the same questions arise: Who was Chinatown for? Who is it for now? And who will it be for next?

The story of London’s Chinatown is part of the ongoing story of Soho. In her book Nights Out, Judith Walkowitz describes how late-nineteenth-century Soho shifted from ‘a dingy, foreign, proletarian quarter into a commodified centre of cultural tourism’. Gerrard Street in particular served as a home for newcomers, a refuge for the displaced and a stage for reinvention and dissent. Between the 1950s and the 1970s, Gerrard Street and its surrounding area grew into a business hub for working-class Cantonese- and Hakka-speaking migrants, most of whom came from Hong Kong’s New Territories and were drawn by the area’s low commercial rents.

According to the 2019 oral history project and exhibition The Making of Chinatown, by the late 1970s, around forty Chinese businesses were thriving on Gerrard, Wardour and Lisle Streets and in the surrounding area (not only restaurants, but also cinemas, bookshops and travel agencies), serving both Chinese and non-Chinese Londoners. Soho has long had a diverse, evolving population, but racism was still commonplace. In the same oral history project, many Chinese restaurateurs described being treated as ‘second-class citizens’.

As part of my PhD, which is about Chinatown-related heritage-making practices, I have spoken to dozens of Londoners – both people who identify as Chinese (including migrants and UK-born individuals of Chinese heritage, adoptees, people of mixed heritage and international students) and people with other heritage (such as Bangladeshi, Nepalese, Thai, Italian, Irish and English) – about their memories and lived experiences of Chinatown. These Londoners told me that Chinatown speaks to different aspects of their identities, such as being ‘migrant’, ‘minority’, ‘queer’, ‘Londoner’, ‘British’ and ‘(British) Chinese’.

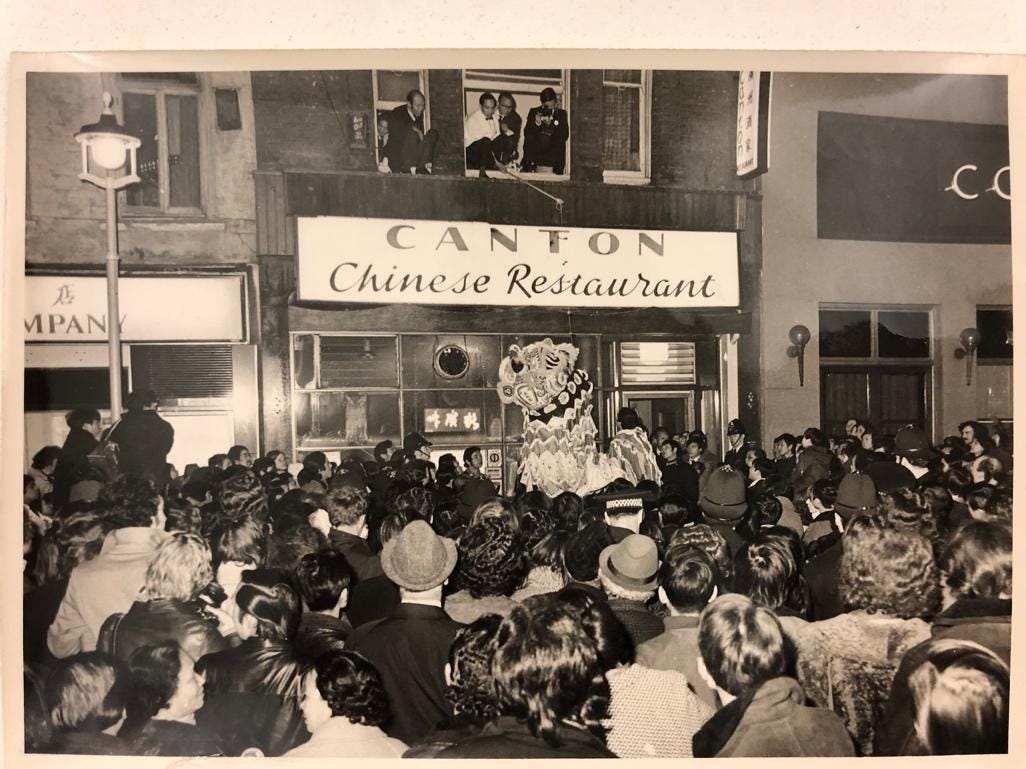

For some of my Chinese interviewees, Chinatown is a symbol of endurance and pride. One interview was with Wai-Lin, who moved with her family from her village in Hong Kong in 1973, when she was four years old. Like many migrants from Hong Kong, her parents worked in London’s growing Chinese catering trade, and her father, a self-taught chef, worked at Canton in Chinatown in the 1980s. Wai-Lin didn’t live in Chinatown, but grew up there. After school, she knew to head straight to her father’s restaurant, weaving through the bustle before finding her father and sitting down to eat char siu rice with him. ‘Now that I think about it … Perhaps Dad just wanted to spend more time with me,’ she says softly.

As I walked the streets of Chinatown with Wai-Lin, stopping at the places her parents and siblings used to work (they roasted ducks, shaped pastries by hand and poured tea for regulars at beloved spots like Young’s and Poon’s and Co), it felt like tracing an old family photo. Chinatown is Wai-Lin’s childhood, even though its material traces have mostly vanished.

At that time, many migrants from the New Territories referred to the district simply as ‘Soho’ in English or ‘wong sing [皇城]’ (royal city) in Cantonese, because of its proximity to Buckingham Palace. The term ‘Chinatown’ gained popularity among Chinese people in the 1980s, especially after the area was officially designated as such in 1985 – a result of a collaboration between Westminster City Council and the London Chinatown Chinese Association (LCCA), which was mainly aimed at attracting tourists.

In an interview as part of the London Chinatown Oral History Project (2011–2013), Harry (Chi Cheung) Lee, the late former president of the LCCA, claimed that he proposed the idea of creating a Chinatown to the council in 1984, when there were already Chinatowns in many other cities globally, and emphasised that it should have an ‘oriental feel’. The Chinatown transformation project involved exoticisation and self-exoticisation, meeting non-Chinese visitors’ expectations of ‘Chineseness’.

Westminster City Council allocated around £235,000 for the Chinatown ‘facelift’ project according to a local news report (see image). The project included building three archways, installing a selection of street furniture and bilingual street signs, and pedestrianising the main streets. In 1986, Peter Levy (son of Joe Levy, a key figure in London’s 1960s property boom) and Jonathan Lane made their first property purchase in Chinatown, laying the foundations for the company that would become known as Shaftesbury Capital (which, as of late 2022, owns around 80% of the area, including forty-three shops and ninety-eight food and drink businesses).

For some of my Chinese interviewees, Chinatown is a racialised label imposed on them that they would rather reject. Others, including Priscilla, talked about reclaiming it as a space that reflects the in-betweenness of their diasporic lives. When Priscilla’s parents moved from Malaysia and Hong Kong to London in the 1980s, they embraced Soho’s nightlife; her arrival later transformed how they related to and consumed Chinatown. At six, Priscilla was enrolled in the UK Chinese Chamber of Commerce Chinese School. She hated the classes, but loved the weekly drive into central London and the family meals that followed.

Lately, Priscilla has been thinking more about what it means to perform Chineseness in Britain. ‘We were born to be Chinese, but in a London, British context,’ she says. ‘How much of my culture and my heritage was performed? And how much of it is what I’ve read through the eyes of Western people – especially walking through Chinatown that’s told back to me from a Western point of view?’ As we stand underneath the Chinese archway on Macclesfield Street – one of Chinatown’s most photographed landmarks – we both feel a mix of familiarity and alienness. Few people know that the three archways were designed not by Chinese architects, but by Richard Swain of Westminster City Council in the 1980s. In a 1984 interview with AJ (available at the Westminster Archives), Swain explained he based the gate design on ‘research at the V&A into authentic Chinese design’.

‘The difference between cultures becomes what defines it in the eyes of the majority,’ Priscilla says. ‘And those differences become the bank of reference representing Chinese culture.’ This is not to say that Chinatown isn’t authentic. For Priscilla, its authenticity lies in lived experience: the memories, emotions and personal connections people have to streets and shopfronts, things that exist beyond the socially constructed borders of an ethnic or racial category.

‘Harry (Chi Cheung) Lee, former president of the London Chinatown Chinese Association, claimed he proposed the idea of creating a Chinatown to the council … and emphasised that it should have an “oriental feel”. The Chinatown transformation project involved exoticisation and self-exoticisation, meeting non-Chinese visitors’ expectations of “Chineseness”’

Chinatowns in white-majority societies have traditionally functioned as ethnic enclaves, often born out of exclusion. London’s first Chinatown in Limehouse, for instance, served as a refuge for Chinese sailors who faced overt racism. Today, newly developed or redeveloped Chinatowns in Europe, North America and Australia are often branded as ‘multicultural assets’ for urban regeneration and tourism.

In 2018, Shaftesbury began using the term ‘pan-Asian’ to describe their approach in Chinatown. Several Chinese business owners I interviewed were wary of the label, arguing that it flattens the rich differences between cultures. As Jenny Lau, author of An A–Z of Chinese Food (Recipes Not Included), put it: ‘You would never talk about pan-European or pan-American food with the same glibness.’

More recently, phrases like ‘authentic ESEA [East and Southeast Asian] experience’ have popped up on Chinatown’s social media, which is funded by Shaftesbury Capital. The use of ‘ESEA’ feels disconnected from the anti-racism political mobilisation among ESEA people, which has fuelled a fast-growing ESEA political identity. It also sits uneasily with the lived reality of many Chinatown workers, who are often first-generation migrants in marginalised socioeconomic positions and who rarely identify with the term ‘ESEA’, even though most can trace their heritage to those regions.

Chinatown holds many meanings and conflicting interests. It is often framed or imagined as a ‘celebration of difference’, but that ‘feel-good’ narrative can obscure as much as it reveals. When we talk about Chinatown in the context of racial justice, we also need to recognise the complex relationship between the business interests of those who own and run businesses there and the social and political needs of those in ESEA diasporas who seek racial equality. These agendas sometimes overlap and intersect, but sometimes they don’t.

China Exchange, the organisation I used to work for, closed in 2024 due to financial difficulties. I’m still grieving. Working there taught me things about myself and the intergenerational traumas I carry. It was a place of connection, where people from all walks of life shared complex, layered stories rooted in the neighbourhood. A place to sit with memories, to make sense of the past. That work needs to continue. It’s why I now volunteer with the newly established Chinatown Collective, where the legacy of China Exchange’s heritage and community work lives on. Alongside other History Champions, I lead walks through the streets and eat in historic restaurants such as Lido, talking through the migrations, labour and food that have both shaped and been shaped by the neighbourhood. We sit with the anger and grief of historical wrongs; we taste the resilience and creativity of the people of Chinatown.

London’s Chinatown is a place of everyday heritage, complex and contested, shaped by those who passed through it and those who are still here. As Bernard P Wong and Chee-Beng Tan’s Chinatowns Around the World shows, Chinatowns take many forms, shaped by their histories, land use, inter-ethnic relations, and local and global changes. They are deeply embedded in their own geographic, political, social and economic contexts. Here, in the former capital of the British Empire, Chinatown’s story remains unfinished. It is part of the longer, ongoing story of London itself.

Credits

Xiao Ma is a heritage practitioner and researcher with a focus on migration. You can learn more about her work here.

Kenn Lam is an illustrator and visual artist whose inspirations range from classical Japanese Ukiyo-e art to traditional Chinese medicine labels and Victorian headstones. You can find his work on his website or his Instagram.

The Chinatown Collective is dedicated to heritage-making and community-building in London’s Chinatown. It is currently organising ‘Looking Back to Look Forward: 40 Years of Chinatown in Central London’ – a year-long festival inviting everyone to reflect on Chinatown’s layered past and imagine its future. For more information, visit chinatowncollective.london.

The Vittles Chinatowns project is guest-edited by Angela Hui.

The Vittles masthead can be viewed here.

My memory of being taken to eat Chinese food in 1970s London centred round Limehouse/ Docklands .. I guess there are historic roots there too .

This article brought back lots of memories of my time working in Soho in the late 80s. I worked on Dean St, at the Groucho club. Down times between shifts or after long nights were often spent in Chinatown, Wong Kei being a favourite place for price and swiftness of service. It's renowned for the rudeness of its waiters but I don't remember that at all - it was super efficient and no time for chat but I think that only seems rude if you're expecting a leisurely dining experience. China Town was a place of ease and familiarity in a Soho that seemed to change weekly - i loved it. I haven't been back for years but hold it in my affection as an English person who simply passed through. Having read this I would love to know more about its evolution and the people who built it (as opposed to this who 'designed' it later on) - if you are still doing your walking tours I will sign up next visit!